Hillary Clinton – the headline maker

Immediately following her Jan. 20 online announcement of her candidacy, Hillary Clinton embarked on a more conventional media blitz that included a series of network TV interviews. With that, coverage of the 2008 election effectively kicked into high gear at an unprecedented early stage of the campaign. And for the first five months of the year, the former First Lady, now Senator, was the campaign’s leading media attraction.

The New York Senator probably offered more media story lines than any other candidate: A former eight-year occupant of the White House trying to balance her own candidacy with her husband’s looming legacy; the first woman making a serious bid for the Oval Office; the immediate front runner in her party’s national polls; and someone with a reputation as a controversial and even polarizing figure in her own right. That mixed grab bag of narratives helps in part to explain the mixed tone of the stories (38% negative, 27% positive, and 35% neutral).

|

Topics of Hillary Clinton’s Coverage Percent of All Stories

|

||

| Clinton | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 68.0 | 63.4 |

| Strategy and Polls | 55.8 | 50.0 |

| Personal Topics | 13.6 | 17.3 |

| Marriage/relationships | 6.1 | 3.7 |

| Gender | 2.0 | 0.7 |

| Domestic Policy | 5.4 | 7.2 |

| Foreign Policy | 9.9 | 7.5 |

| Iraq War | 9.9 | 6.3 |

| Public Record | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 0.7 | 2.0 |

Her front-runner status was the primary fascination of the press early on. Fully 56% of Clinton stories were about polls, tactics and performance on the stump in the first five months. Fewer stories than the norm (14% vs. 17% overall) were about her personal background, however, this number that suggests journalists may have felt much of this was already known. As for her ideas for where she would take the country, only one received a significant amount of attention—her position on the war in Iraq (10% of stories), a percentage higher than election coverage overall devoted to the war. The dynamic here may well be that journalists examining a front runner tend to examine possible weakness, in this case the fact that Clinton at first supported the war and changed her position over time.

The tone of Clinton coverage varied a good deal by medium. Newspapers, for example, treated her more favorably (giving her roughly twice the percentage of positive stories as elsewhere).

And a good deal of her negative coverage can be attributed to a media platform that has been taking on the Clinton family since they moved into the White House in 1993. Nearly 20% of the nearly 300 Clinton stories examined in this report aired on conservative talk radio, a genre that many observers believe found its voice and primary target after Bill Clinton’s 1992 election. In this campaign, conservative talkers in the early months have a new target. Nearly nine-out-of-ten Clinton segments in conservative talk (86%) were clearly negative in tone. The enmity of some of those hosts toward the New York Senator is so pronounced that both Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity have on occasional lauded her Democratic rival Barack Obama, with his chief virtue apparently being that he is not Hillary Clinton.

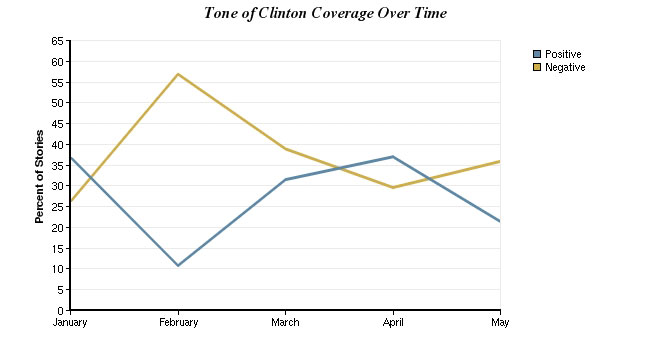

The trajectory of Clinton’s coverage over time followed something of a roller coaster route. Her announcement in January helped make that a largely positive month. Coverage became notably more negative in February. It improved somewhat in March, but it was not until April that the positive again outweighed the negative. Then it slumped again in May.

One factor that remained constant throughout the first five months of the year—and it would help explain the continuing focus on Clinton but not the up and down tone—was her status as front runner in the polls. A track of Gallup polls from January through May shows her as the consistent leader in the national Democratic polls, most often registering in the 30-40% range. As the election season wore on, and Clinton began to build on her lead, some stories even began focusing on the “I-word,” (inevitable).

Rudolph Giuliani– front runner facing doubters

There are a number of striking similarities in the campaign dynamic and coverage of the two New York candidates in this race. (Clinton and Giuliani were ticketed to face each other in the 2000 New York Senate race when prostate cancer forced Giuliani out of the campaign.) Like Clinton, the former New York mayor has been his party’s leader in the polls from the start. He has also been the GOP’s top newsmaker (9% of all stories). And he, too, has received more negative coverage than positive and in much the same proportion as Clinton (37% negative, 28% positive and 35% neutral).

If Clinton has faced questions about her likeability as a general election candidate, Giuliani confronts a continuing issue in his quest during the primaries: Is he too socially liberal for the GOP base? Can toughness on terrorism convince conservatives to overlook other disagreements with him?

In the early phases of the campaign,these issues made up a notable portion of Giuliani coverage. All told, his ideas on domestic policy made up 22% of Giuliani stories, far more than the 7% norm.Almost all of that (19%) was about Giuliani’s perceived biggest electoral weakness in the primaries, abortion.

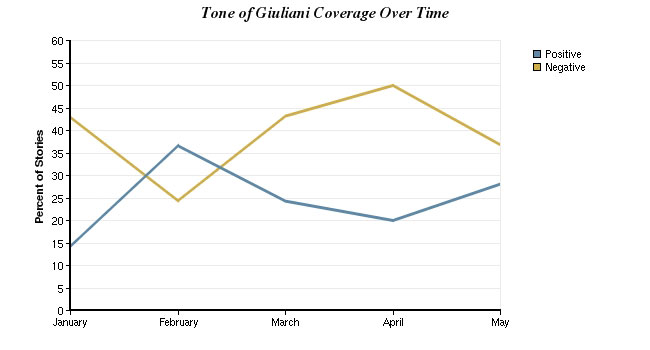

The tone of coverage of Giuliani fluctuated, but the only month in which he actually enjoyed more positive than negative press (37% to 24%) was in February, when he officially announced his candidacy. After that, the tone steadily dropped, picking up again in May. Throughout the five months, however, the tone remained more negative than not.

But the negative tilt to the coverage differed by medium. Front-page coverage of Giuliani in the newspapers studied tended to be more negative than anything else (six out of 12), thanks in part to rough coverage from his hometown paper, The New York Times. The same was true on network evening newscasts (six negative pieces out of 14).

There was better news for Giuliani on the Fox News Channel where positive stories dominated over negative. (Eight out of 18 were positive, while three were negative). But perhaps indicative of the conservative qualms about Giuliani’s more socially moderate views, on conservative talk radio, nine out of the 16 segments were negative, while just four were positive.

One reason why a non-announced candidate like Fred Thompson attracted significant media attention in the first five months—and why there was also flurry of press interest in a Newt Gingrich candidacy—was a dynamic that emerged in the early phases of this campaign. Many Republicans were uneasy with their choices. Thus, the idea of Giuliani as a shaky front runner has been a consistent story line.

Barack Obama—The Rising and Fading Star?

Barack Obama made his introductory mark on the national political scene with a compelling and original speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention in Chicago. When he arrived in Washington as a freshman Senator from Illinois, speculation about his running for President struck some observers as an act of impudence and others as an echo of John Kennedy, another young Senator who jumped over his elders to run for the White House. And when he began making trips to Iowa and New Hampshire, journalists marveled at a charisma that some said echoed not only John Kennedy, but even more so his brother Robert.

That star appeal was evident in the press coverage of Obama in the first five months of the year. With 47% of the stories clearly offering a favorable tone about his candidacy, he was the media darling among major contenders. In all, he was three times more likely to get positive coverage as negative, and nearly twice as likely to get favorable stories as Clinton was. He was the only prominent candidate among the Democrats whose coverage was more favorable than neutral (38%).

The treatment, if one looks more closely, was even more favorable in some of the most important media of all. Obama enjoyed particularly favorable coverage from three media in particular—newspapers (70% positive stories), network morning news (58% positive), and network evening news (55%). Only in conservative talk radio was the coverage of Obama more negative than not.

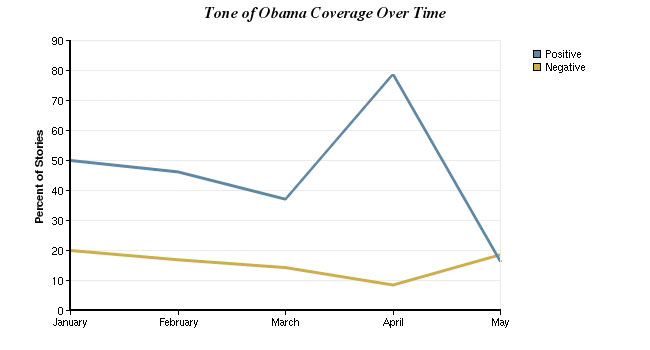

For all that good news, however, the trajectory over time of Obama coverage suggests a more complicated story. While the coverage tilted 30 points toward the positive in January and February, it jumped to a 70-point positive differential in April. But by May, there were signs of trouble. The coverage had become far more neutral, with positive stories and negative more equally divided.

|

Topics of Barack Obama’s Coverage Percent of Stories

|

||

| Obama | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 57.1 | 63.4 |

| Strategy and Polls | 38.3 | 50.0 |

| Fundraising | 15.0 | 7.3 |

| Personal Topics | 17.9 | 17.3 |

| Race | 8.8 | 1.9 |

| Domestic Policy | 6.3 | 7.2 |

| Foreign Policy | 8.3 | 7.5 |

| Public Record | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 7.5 | 2.0 |

Do the data offer any empirical hint as to why he enjoyed the largest percentage of clearly promising stories? One reason may be that twice as many stories as the norm (15% vs. 7% overall) were about fundraising, an area where Obama exceeded expectations. Fewer stories than the norm (38% vs. 50% generally) were about his standing in the race—where reporters might have focused on his inability to gain much ground on Clinton. The level of coverage of Obama’s personal biography—one of the strongest selling points of his campaign—was roughly on par with candidates generally. By one other yardstick, Obama and his campaign were enjoying another advantage some campaigns might envy. They initiated fully 65% of all the stories that focused on him, substantially more than the 46% overall. That suggests that the candidate may be enjoying somewhat greater control of his coverage than other candidates, even though his campaign, according to private comments made to us by some political reporters, is not reputed to be as disciplined or organizationally nimble as Clinton’s.

John McCain –bearing the brunt of bad news

If the senior Senator from Arizona was considered by some observers to be the likely Republican frontrunner when the race began, he quickly ran into difficulties with fundraising, disappointing poll numbers and significant staff turnover. That all helped make McCain a newsworthy candidate. But the tenor of the coverage, particularly in the early months of the campaign, was overwhelmingly negative, far more so than for any other major candidate.

In volume of coverage, McCain (at 7%) trailed the two leading Democrats, Clinton and Obama, by a considerable margin. But for a candidate whose campaign was foundering, he received almost as much coverage as the Republican front runner in the national polls (Giuliani) and more than the leader in Iowa (Romney). McCain as a disappointment was almost as big a story as Giuliani was as a surprise frontrunner.

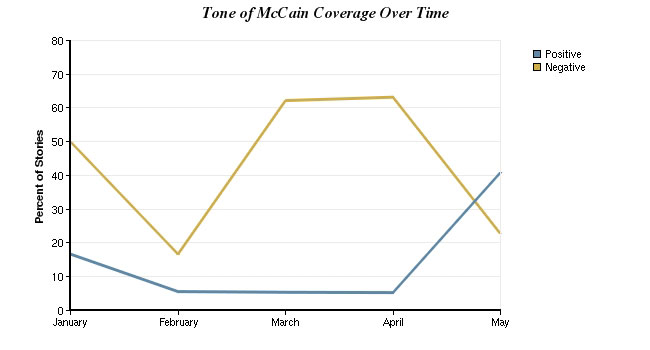

That may explain the most striking feature of McCain’s coverage, its negative tone. From January through May, stories about McCain were four times more likely to bear bad news than to be flattering. In all, close to half of all stories produced about the Senator and his campaign (48%) were clearly negative. Only 12% registered as positive in tone. (Four in 10 of the McCain stories were neutral.)

Why was McCain on the receiving end of so much unfavorable press? In a campaign dominated by coverage of strategy and tactics, there are some clues. Fully 60% of his coverage, for example, concerned his worse-than-expected standing in the polls, compared with 50% generally. And 51% of those McCain horse race stories were clearly negative in tone.

Typical of this coverage was a March 8page-one story in the Wall Street Journal warning, in the first sentence, that “Sen. John McCain is facing unexpectedly formidable challenges despite courting the party faithful during his seven-year wait on deck for a shot at the White House.”

“A new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll shows the Arizona Senator trailing Rudy Giuliani by more than 20 percentage points—and encountering doubts in the party about his age and steadfast support for the Iraq war,” the story continued.

The only month in which McCain’s coverage got more positive was May, when he was able to showcase some of his strengths in two GOP debates. Then, his favorable coverage jumped from 5% in April to 41% in May. But since early coverage of McCain was quite consistent across most media sectors, the story of a candidate in strategic trouble was a dominant message about him.

|

Topics of John McCain’s Coverage Percent of Stories

|

||

| McCain | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 64.5 | 63.4 |

| Personal Topics | 4.1 | 17.3 |

| Domestic Policy | 11.6 | 7.2 |

| Immigration | 4.1 | 0.7 |

| Foreign Policy | 16.5 | 7.5 |

| Iraq War | 14.9 | 6.3 |

| Public Record | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2.0 |

What other topics was the press looking at with McCain? His controversial position on Iraq—supportive of a military buildup–got more coverage (15%) than candidates’ generally did for the ideas about the war (6%). But his heroic biography, including his story as a former Vietnam-era prisoner of war and third generation soldier, got less coverage than the overall (4% vs. 17%generally).The list of topics the press focused on about McCain, in other words, tended toward the controversial and the difficult rather than the flattering.

John Edwards – The Husband and, Oh, Candidate, Too

Now in his second presidential campaign, John Edwards—the Democrats’ 2004 vice-presidential nominee—has had real trouble competing for media attention with the two celebrity candidates who have also been No. 1 and No. 2 in the polls, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. The two sitting Senators were presented as locked in a two-way race.In most stories the primary focus was either Clinton or Obama (294 and 240 stories) and the secondary focus was also evenly split between Clinton and Obama (148 to 147).Edwards was way behind with only 71 primary and 49 secondary mentions.

As the major figure in only 4% of the campaign stories in the first five months of the year, Edwards ended up in the middle tier of candidates in terms of coverage. But even that number is in some ways deceptive. Were it not for the month of March, when Edwards’ wife Elizabeth announced that her breast cancer had recurred, the former North Carolina Senator would have been in the third tier of candidate coverage in the outlets studied. That lack of media attention came despite the fact that Edwards had been leading, for much of this time, in the polls in Iowa, and that he has consistently polled in the double digits in the national Gallup surveys.

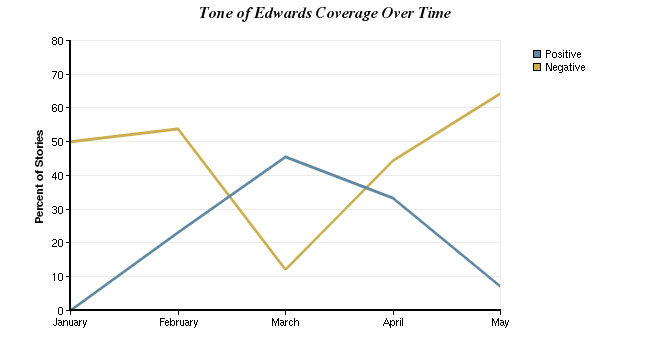

While the tone of Edwards’ coverage was split (31% positive, 34% neutral, 35% negative), and thus more positive than Clinton’s and less positive than Obama’s, that is only part of the story.

The coverage began badly for him, with very little coverage in January, as his rivals were gearing up. And when the press did take more notice in February, the coverage was mostly negative (54%). He was largely invisible again in April. And in May, when he became a focus of attention again, 64% of the stories about him were negative and only 7% were favorable.

Elizabeth Edward’s illness made a measurable difference in how he was treated. March, when she announced her cancer’s return, was the only month of substantial media attention in which John Edwards’ favorable coverage outweighed his negative (45% vs. 12%). Elizabeth Edwards, in turn, got even more coverage than he did that month and none of it was negative.

Edwards’ coverage also varied noticeably by medium. On cable, negative stories outweighed positive by 2-to-1, thanks entirely to prime-time cable programming, both on Fox and MSNBC. It was evenly split in newspapers.

|

Topics of John Edwards’ Coverage Percent of All Stories

|

||

| Edwards | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 35.2 | 63.4 |

| Personal Topics | 42.3 | 17.3 |

| Personal Health | 31.0 | 5.1 |

| Domestic Policy | 14.1 | 7.2 |

| Foreign Policy | 7.0 | 7.5 |

| Public Record | 0 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2.0 |

By one measure, Edwards might have seemed more in control of his coverage than most other candidates. He or his campaign initiated most of the of the press coverage (56%), which was higher than the norm (46%).To some degree, the focus on Edwards may have been, if not where he would have liked, at least on topics that may have worked for him. Not surprisingly, far more coverage of Edwards was about his family’s health than was true for candidates overall (31% vs. 5%). And more coverage was about his ideas about domestic policy (14% vs. 7% generally), particularly his populism on taxes, health care and other social issues.

Fred Thompson—The Once and Future Politician

If the press is sometimes accused of preferring celebrity over politics in its news agenda, the candidacy of Fred Thompson is the perfect union. The former prosecutor turned U.S. Senator turned actor played no-nonsense District Attorney Arthur Branch on NBC’s “Law and Order” series for the last six years.

When he began hinting in March that he might run for president, communications lawyers predicted that TV stations would have to take reruns of the program with Thompson off the air. But the press began covering with favorable anticipation about the effect the actor might have on changing the dynamics of an unsettled GOP field.

“The betting money shows Thompson with a real shot right now…with only Rudy Giuliani really ahead of him,” declared MSNBC’s Chris Matthews on a show back in late May, long before the ex-Senator was an official candidate. “Does Thompson have the right appeal for the Republican base? It looks like he does.”

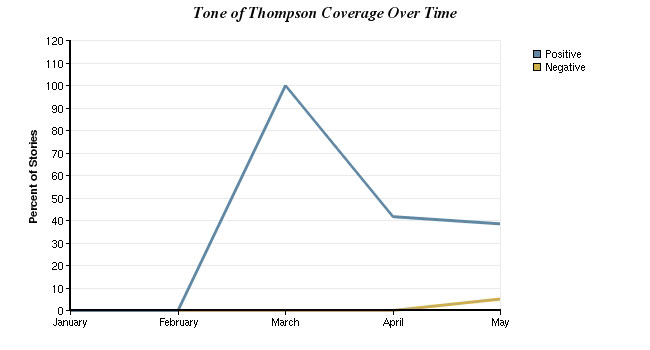

By the time the first five months of the year were over, three things stood out about Thompson’s coverage. The first was how positive it was. Like Obama, nearly half the stories about him (46%) carried a clearly positive tone, and more than half were neutral (51%). Almost none, just 4%, was negative.

|

Topics of Fred Thompson’s Coverage Percent of all stories

|

||

| Thomson | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 84.2 | 63.4 |

| Personal Topics | 12.3 | 17.3 |

| Personal Health | 10.5 | 5.1 |

| Domestic Policy | 3.5 | 7.2 |

| Foreign Policy | 0 | 7.5 |

| Public Record | 0 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 0 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2.0 |

The second feature of the coverage is that it was media driven. More than half of all the stories (54%) were initiated by the press, roughly double the norm. If other candidates were trying to figure out ways to drive coverage about them by staging events or staking out dramatic positions, Thompson, the candidate-in-waiting, had no such burden.

The third feature of the Thompson story is that almost all of the coverage (84%) was about his impact on the race. His ideas, his policy positions, even his biography and record, received negligible coverage. This may have suited for Thompson just fine. A study of his website in these early days, for instance, found that he was the only candidate whose site did not feature a section on his ideas or policy positions.

This may also have helped explain why his coverage was so positive. Thompson in these months was the candidate people were waiting for. Some Republicans wondered if another former actor was the eagerly awaited 2008 version of Ronald Reagan. But little about anything else was reported about him.

It would come later, after September, that journalists would begin to wonder if he was really as conservative as advertised, a poor or rusty performer on the stump, or lacked the fire in the belly.In a report filed only two days after Thompson announced, ABC’s Jake Tapper cited questions about “his work ethic,” and whether “the 65 year-old will have the energy for the rigorous road to Pennsylvania Avenue.” In the Senate, Tapper noted, “Thompson was not known as a workhorse.”

But the nature of that coverage is the subject of further study.

Mitt Romney – the third man

Largely a mystery man when he entered the Republican presidential field, Mitt Romney’s campaign strategy and tactics seems to have impressed the media, even as the press raised questions about his policies, his record, and even his religion.

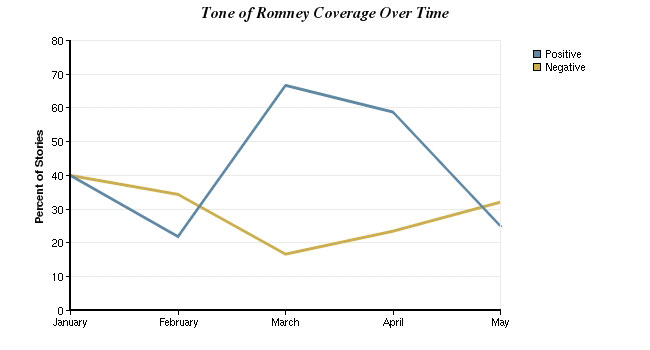

That dichotomy may go a long way toward explaining coverage that is the most evenly balanced of all the major GOP candidates—34% was positive, 35% was neutral and 31% was negative. And though he trails Giuliani and McCain in the amount of coverage generated, Romney has (at 5% of the coverage) even this early managed to distance himself from the second-tier of Republican hopefuls who were virtually ignored by the media in the first five months of the year.

<

Helping to bolster that positive press was the perception that the former Massachusetts governor has run a strategically smart campaign. While he has trailed substantially in the national GOP polls, Romney’s emphasis on and stronger showing in the two early and crucial caucus/primary states of Iowa and New Hampshire have put him in competitive position to potentially emerge as a major candidate.

Thus coverage of Romney’s fortunes in the “horse race” (polls, tactics and performance on the stump), which accounted for 40% of Romney’s stories, and his fundraising skill (13% of his stories) helped created a flattering portrait of a candidate probably doing better than expected. Fully half of these stories (52%) had a positive tone for Romney, more than twice the number (24%) that were negative.

|

Topics of Mitt Romney’s Coverage Percent of All Stories

|

||

| Romney | AllCoverage | |

| Political Topics | 55.7 | 63.4 |

| Strategy and Polls | 39.8 | 50.0 |

| Fundraising | 12.5 | 7.3 |

| Personal Topics | 28.4 | 17.3 |

| Religion | 22.7 | 2.1 |

| Domestic Policy | 9.1 | 7.2 |

| Abortion | 6.8 | 2.9 |

| Foreign Policy | 3.4 | 7.5 |

| Public Record | 3.4 | 1.4 |

| Electorate | 0 | 1.1 |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | 2.0 |

When the fundraising totals for the first quarter of 2007 were reported in early April, for example, Romney’s had collected $20 million, easily outdistancing his Republican rivals and earning a front-page New York Times headline: “Romney leads G.O.P. in Money, Tapping Wall St. and Mormons.” It was when the media got around to the other subjects that things became more difficult.Only 8% of the stories about Romney’s personal background, including his membership in the Mormon Church, were positive, while more than a third (36%) were clearly negative in tone. (In a recent Pew Research Center for the People & the Press Poll, 62% of the respondents said their religion is “very different” from the Mormon faith.)

Romney has also had to battle the perception that he is a “flip-flopper,” a man who governed as a moderate chief executive of Massachusetts, but has now tacked to the right in the Republican primary fight. Like both Giuliani and McCain, Romney still must convince many conservatives he is an acceptable candidate.

Over time, after a slow start in February, Romney’s coverage got more positive in March and April, but then became more negative in May. That month, coverage of him increased to its second highest level, behind only February. But his performance in debates, while not panned, failed to dazzle the journalists who score such events. In the early phases of this campaign, Romney the man seemed less intriguing to the press than Romney’s chances in the race.

Announcement and tone

Some might also suspect that candidates get their best coverage around their announcement, when all is still ahead and anything is possible.That was not the case.

Only two of the top candidates enjoyed announcements where their positive coverage clearly outweighed their negative—Clinton and Giuliani. For two others, Obama and Romney, relative newcomers to national politics, the coverage the week following their announcements was more divided. And one candidate, McCain suffered more negative than positive coverage the week his campaign officially began.

|

Tone of Coverage of Candidate Announcements Percent of All Stories

|

|||

| Candidate & Date | Positive | Neutral | Negative |

| Hillary Clinton 1/20-1/27 | 42.9 | 34.7 | 22.4 |

| Barack Obama2/10-2/17 | 30.8 | 46.2 | 23.1 |

| Joe Biden1/31-2/6 | 5.6 | 44.4 | 50.0 |

| John McCain4/25-5/2 | 19.0 | 38.1 | 42.9 |

| Mitt Romney 2/13-2/20 | 26.9 | 42.3 | 30.8 |

| Rudy Giuliani2/13-2/20 | 37.5 | 62.5 | 0 |

One other candidate suffered from almost no good news the week he announced—Joe Biden. That media flop is easy to understand. Biden stepped on his announcement by making remarks about Barack Obama that raised questions about his racial sensitivity.

For McCain, the numbers raise the question of what constitutes a formal announcement. McCain told talk show comedian David Letterman he would run on February 28. But he formally announced his candidacy on April 25, giving his announcement speech on that date. By then, the date measured here, trouble in the polls, in fundraising and the management of his campaign, had already begun.

[1]In a statement Biden made to the New York Observer on the eve of his announcement, Biden said, “I mean, you got the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy,” Biden said. “I mean, that’s a storybook, man.”