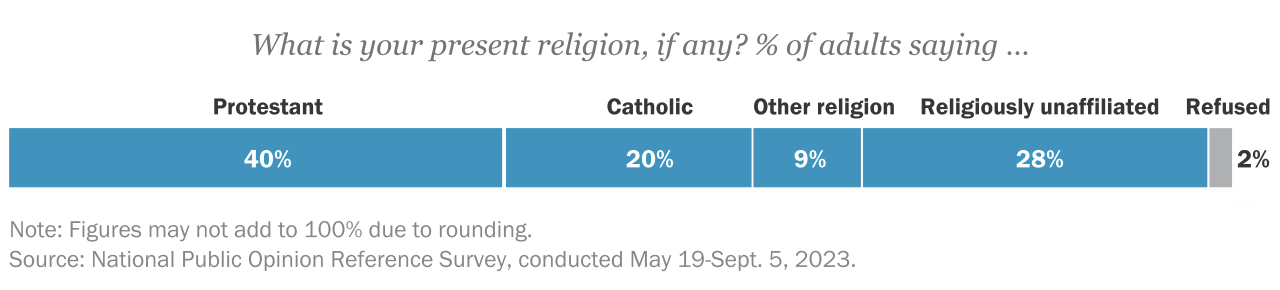

Despite growth in the share of people who are not religiously affiliated, religion continues to have significant consequences for American society and politics. As a result, we take great care in how we measure religious affiliation and related attitudes and behaviors.

The decline of religion in the United States and many other Western democracies is an important feature of the 21st century. The decline is seen in many ways, perhaps most consequentially in a downward trend in the percentage of people who say they belong to any organized religion. This measure is sometimes called “religious preference” or “religious identification” instead of affiliation. But, in any case, it refers to how people answer a question about whether they have a religion and, if so, what it is.

“Our question has evolved over time as the composition of the U.S. population changes and attitudes about religion shift.”

Our general rule that “you are who you say you are” works pretty well with religious affiliation. But the devil, as they say, is in the details. (In fact, our colleagues have written multiple publications on how we measure religious affiliation.)

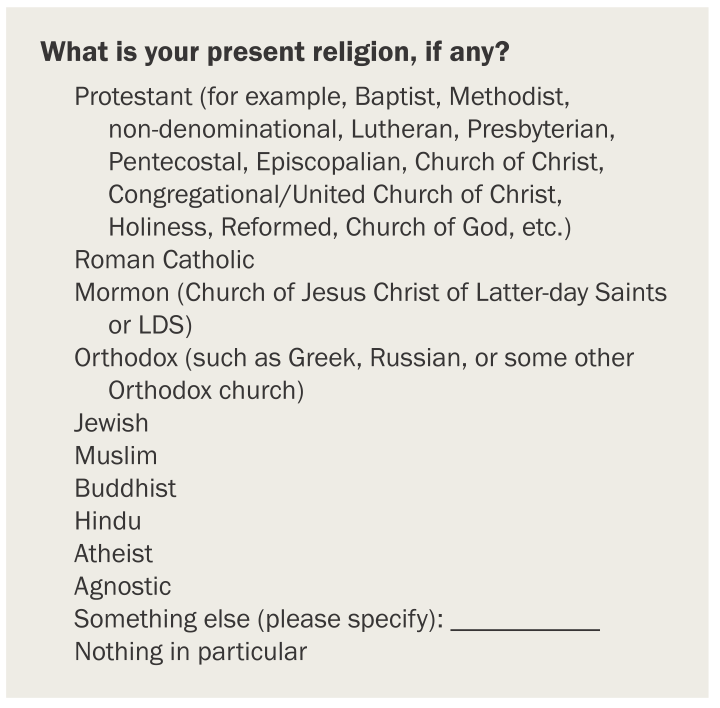

Pew Research Center actually relies on several questions to categorize a person’s religion, beginning with an initial question about broad faith traditions. Members of our American Trends Panel are asked, “What is your present religion, if any?” and offered the options shown below. Other polling organizations use a similar question, though often with a different list of options or most of the same options but in a different order.

Our question has evolved over time as the composition of the U.S. population changes and attitudes about religion shift. Younger generations have been coming to adulthood with much lower levels of religious affiliation than older generations did, while immigration has brought increasing numbers of non-Christians to the country.

How Pew Research Center’s measure of religion has changed

The previous standard version of our question was based on one used by Gallup for many years: “What is your religious preference – Protestant, Roman Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, or an Orthodox church such as the Greek or Russian Orthodox Church?” In 2003, recognizing the growth and importance of the U.S. Muslim population, the Center added “Muslim” as an option.

Notice that there was no explicit option offered for people who do not have a religious affiliation. People who were atheist, agnostic or simply did not identify with a religion had to volunteer that fact to an interviewer. In a society as religious as the U.S., secular people may have felt some subtle social pressure to choose a religion. Still, in 2006, an average of roughly 12% in our telephone surveys volunteered that they had no religious affiliation.

(During the 1990s and early 2000s, we occasionally used a more detailed religious affiliation question on surveys explicitly focused on religion. That question asked first about broad faith groups, including Islam, then about denominations and subgroups, including different categories of the unaffiliated.)

We revised the standard religious affiliation question in 2007 after extensive testing that compared different approaches. We added “Hindu” and “Buddhist” as explicit options, in part because of the growing number of Asian immigrants in the U.S. We also added three options to capture the secular or less religious population: “atheist,” “agnostic” and “nothing in particular,” which together we call the religiously unaffiliated.

The new question produced very different results. The share of unaffiliated rose from about 12% to 16%. This suggests that some people are loosely attached to their faiths, and when given the explicit opportunity to say they are atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular, they take it. What resides in a person’s soul or innermost thoughts may be beyond our ability to determine (though we’ve tried). But the fact that we saw this change suggested that some people found themselves on the border between nominally identifying with a religious tradition – perhaps the one they were brought up in – and no longer fully believing, practicing or wanting to claim that religion as theirs.

Given that Christians remain a majority of the U.S. population, our question is a bit of a hybrid. The options we offer consist of entire faith traditions (Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and Judaism) and subgroups within Christianity (such as Protestantism, Catholicism, Orthodoxy or Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), along with three flavors of secularism or disaffiliation.

This array of response options reflects the fact that faith traditions other than Christianity currently make up very small shares of the U.S. public. A typical survey sample does not yield enough interviews with people in these groups to allow us to look in detail at each one. But within one of the Christian subgroups – Protestantism, the largest American faith tradition – we sometimes look below this second level by comparing people who affiliate with different Protestant traditions.

At this more granular level, some people aren’t sure what category they fit in, or they don’t see themselves in the categories that we offer. Like most faiths, Protestantism is amazingly diverse, with a multitude of different denominations and many churches that don’t identify with any denomination at all. This complicates our ability to place people within traditions of Protestantism. In response, our questionnaires have grown to accommodate the variety of churches and faiths that Protestants currently embrace.

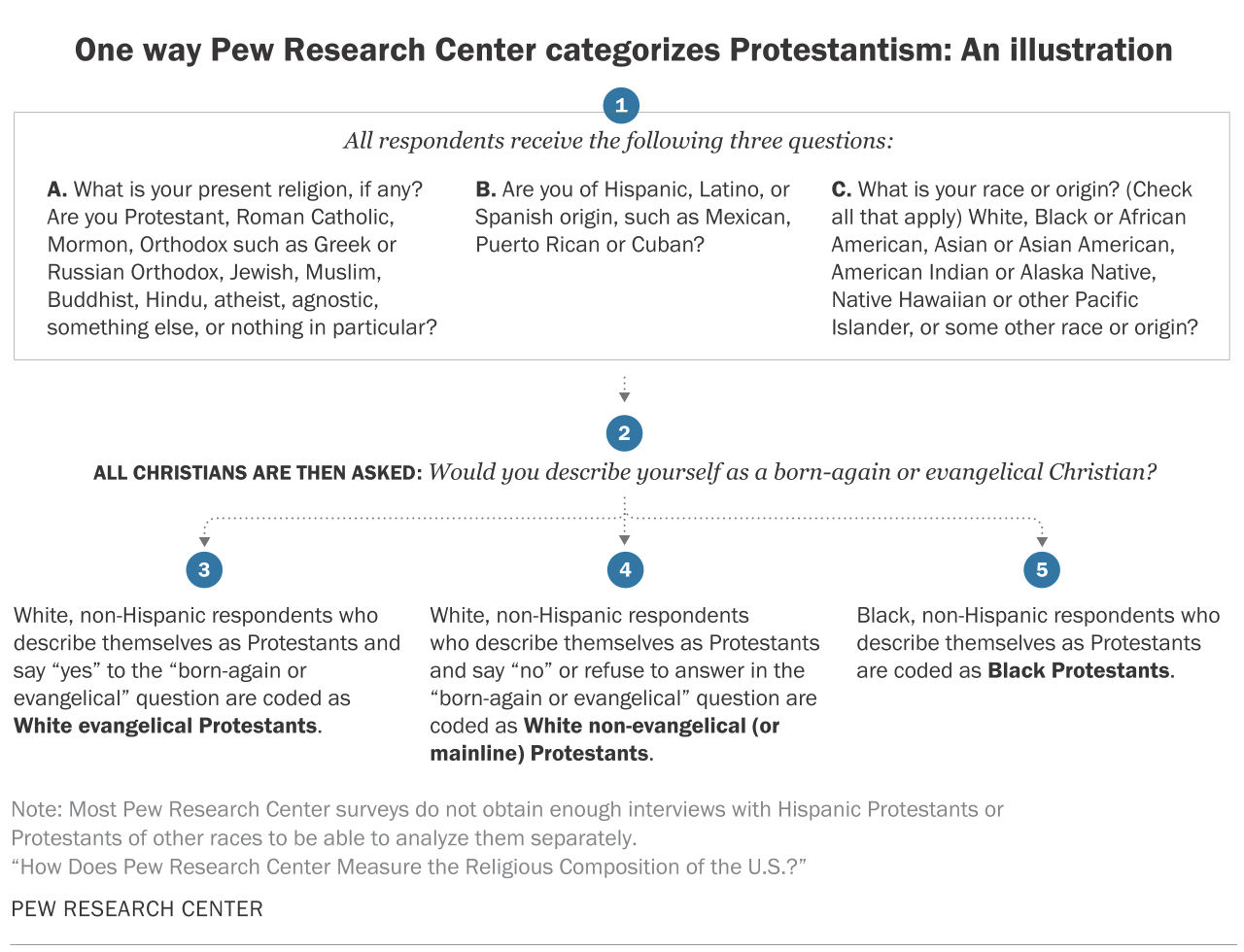

Who is considered evangelical?

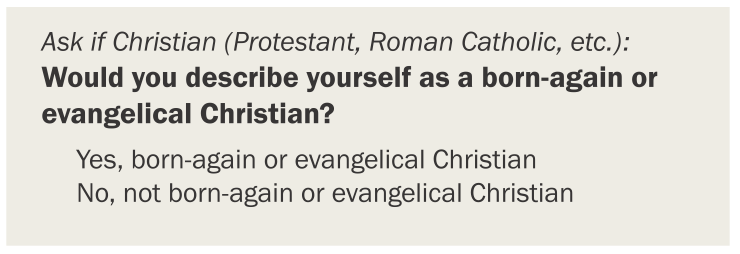

One of the largest and most influential subgroups within Christianity in the U.S. is evangelical or born-again Christians. While there is no single, agreed-upon definition of who is evangelical, churches within the evangelical tradition tend to share religious beliefs (including the conviction that personal acceptance of Jesus Christ is the only way to salvation); practices (like an emphasis on bringing other people to the faith); and origins (including separatist movements against established religious institutions).

Pew Research Center uses two ways of identifying evangelicals. The simplest and most common is to ask all Christians this question:

Would you describe yourself as a born-again or evangelical Christian?

White, non-Hispanic Christians who are Protestant and say “yes” to the born-again question are categorized as White evangelical Protestants. This group has become a mainstay of the Republican Party, and Republican candidates routinely receive upward of 80% of its vote.

The other method of identifying evangelicals uses a detailed set of questions asked of Protestants to identify what specific denomination they consider their own. These questions can reliably identify most people who are affiliated with the evangelical Protestant tradition. But for a sizeable minority of respondents who are unable to provide a clear answer to the denomination question, the born-again question and sometimes the respondent’s race are used to classify them as White evangelical Protestant, White mainline (non-evangelical) Protestant or historically Black Protestant.

Balancing conflicting principles: The special case of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Our general rule when referring to a specific group is to use the name that they prefer. That is easy enough to do when writing about them, but confusion can sometimes arise when we are using a survey to identify who is (and isn’t) a member of the group if the group’s preferred name is not well known.

The leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has expressed in recent years a desire to no longer have church members referred to as Mormons, a term derived from one of its holy scriptures – the Book of Mormon – and which the church long embraced. The Mormon label is generally familiar to Americans, many of whom may not know the church by its full, official name. Thus, a dilemma for us: How do we refer to the church in our religious identification question in a way that is respectful of its wishes and its members but also obtains an accurate measurement of affiliation?

Our standard telephone survey question about religion simply included the term “Mormon” in a list along with several other faith traditions. In the response options visible to interviewers, but not read to respondents, was a parenthetical reference to the church’s official name:

Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints/LDS)

This type of guidance is frequently used in telephone surveys. In this instance, it would help an interviewer correctly code a response if the person being interviewed did not use the term “Mormon” but instead said they were a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or the LDS church.

When we began conducting self-administered surveys (that is, surveys where there is no interviewer; respondents simply read and answer the questions online or on paper), we used similar text as a response option:

Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or LDS)

But could a version without a reference to “Mormon” obtain accurate results?

We conducted an experiment to test this by showing one group of respondents the standard version and a second group a version that omitted the word “Mormon.”

The version that omitted “Mormon” and just read “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS)” was clearly confusing to some people. It produced estimates nearly twice as large as the standard version. Researchers hypothesized that some Christian respondents saw “Church of Jesus Christ” and chose it without reading further or recognizing the full name of the church.

While this exercise did not result in a change to our standard question, it did provide us with an opportunity to standardize how we describe members of the church in our reporting and graphics. Going forward, upon first mention of the views or characteristics of the church’s members, we will use the full name along with a parenthetical reference to Mormons: “members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (widely known as Mormons).” Shorter references when space is tight – for example, in a small chart – will refer to “Latter-day Saints (Mormons).”

How we measure and account for other faith groups

Even though the religion question is one of the lengthiest demographic items in our surveys, the range of possible affiliations is far larger than is captured by the 11 options we offer.

Survey respondents are also given an explicit option of “something else” and asked to write in their church or faith. We carefully review these volunteered responses and, where appropriate, assign them to existing categories or place them into a catch-all “Other” group.

This process of reading the volunteered responses and using them to categorize people is called “back coding” and is an important part of the measurement of religion (as well as race, and sometimes other demographic measures such as sexual orientation) because the options offered in the survey do not cover all the possible ways people think about their identities.

Many of the volunteered responses to the religious affiliation question can be assigned to an existing category. “Christian” or “just a Christian” are perhaps the most common write-in responses, and these individuals are usually back coded as Protestant. Other responses not listed explicitly as options but categorized as Protestant are Seventh-day Adventist, Quaker, Mennonite and many more.

After the back coding is complete, the Other category is home to approximately 2% of the sample. It includes Pagans, Unitarian Universalists, Wiccans, Rastafarians, Deists, Sikhs, people who write in “spiritual” and those who list two or more affiliations, among other groups that constitute very small shares of the U.S. public.

Studying small religious groups

In our surveys of the general public, we encounter people who identify with religious traditions that represent a very small percentage of all Americans. That usually means we do not have enough interviews to be able to describe the groups in any detail. But occasionally we conduct special, targeted surveys to be able to provide an in-depth portrait, as we have done with U.S. Jews, Muslims and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. These studies typically involve drawing very large samples that are somewhat concentrated in areas with larger numbers of the target population.

In our surveys of Muslim Americans, we are able measure what branch of Islam each respondent identifies with (16% Shiite, 55% Sunni). We can distinguish between converts (21% of all U.S. Muslims in 2017) and those who were raised Muslim.

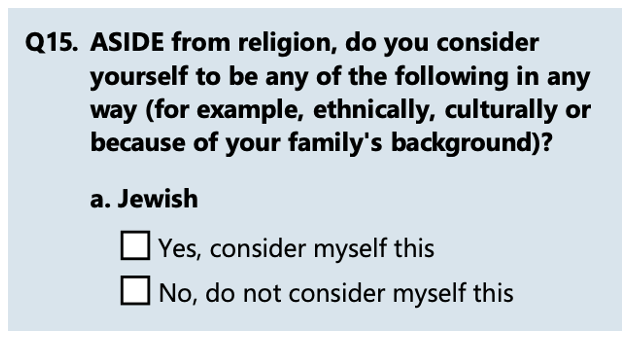

Studying Jewish Americans brought a unique measurement challenge: A sizeable number of people consider themselves to be Jewish ethnically, culturally or by family background. They may have been raised Jewish or have a Jewish parent, but do not claim Judaism as their religion.

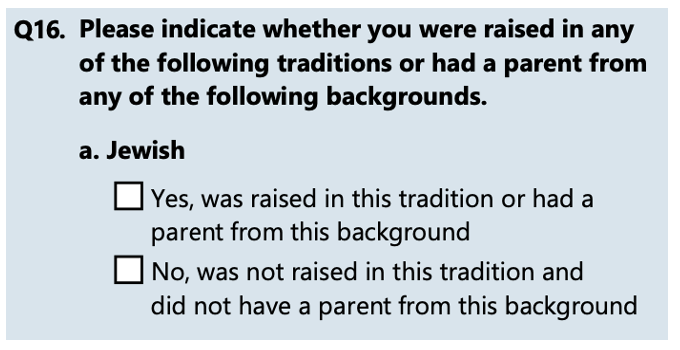

To better understand the views and experiences of all kinds of Jewish Americans, Pew Research Center conducted a complex two-part study in 2019-2020. The first part screened a very large random sample of the public to identify people who said that they are Jewish in response to our standard religion question. But the screener also sought additional people who potentially could be part of a group we call “Jews of no religion.” The main survey included questions that further identified or confirmed those who could be a part of that group. Ultimately, they needed to meet three criteria: 1) they responded atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” to the standard religion question; 2) they consider themselves Jewish in any way aside from religion; and 3) they were either raised in the Jewish tradition or had one or two Jewish parents. These “Jews of no religion” constituted 27% of all Jewish Americans in the 2019-2020 survey.

Having a large sample of Jews made it possible to describe this population in much greater detail, such as how identification with different branches of Judaism varies by age. For example, the study found that, compared with older Jewish people, the Jewish population under age 30 includes larger shares of both Orthodox Jews and Jews with no denominational identity.

What ‘religious affiliation’ does not mean

Affiliating with a religion does not necessarily mean that a person holds any particular set of beliefs or engages in particular practices. If someone tells us they are Catholic, we consider them Catholic even if they also tell us that they never go to Mass or confession, or even that they do not believe in God. Similarly, people who do not affiliate with a religious tradition may still believe in God, pray regularly or say that religion is very important in their life. They are categorized as unaffiliated but may still be considered religious.

Getting a full sense of the role of religion in a person’s life may require understanding “the three B’s” – believing, behaving, belonging. Religious affiliation is mainly about belonging, but knowing about a person’s beliefs and behaviors is important to create a well-rounded portrait of their religiosity. We routinely ask all three kinds of questions in our surveys.