The 2011 Political Typology is the fifth of its kind, following on previous studies in 1987, 1994, 1999 and 2005. The events of the past six years have resulted in a substantial shift in the political landscape, producing new alignments within each of the two parties and in the middle. In particular, views about the role of government increasingly separate the Republican and Democratic groups, which represents a change from 2005 when national security was more strongly associated with partisanship. This is partly a result of the public’s attention turning more to domestic and economic issues. Other core values also continue to divide the public, including views of business, helping the poor, environmentalism and immigration.

One of the dominant trends in American politics over the past decade has been the continuing polarization of American politics. The political chasm between “Red” and “Blue” America that opened in the latter half of the Bush presidency has further widened since Barack Obama took office. Yet to view American politics solely through the lens of partisan strife overlooks significant differences within these partisan bases, as well as within the political center. While we are seeing more doctrinaire ideological consistency at each end of the spectrum, there is, if anything, even more diversity of values in the political center.

The typologies developed by the Pew Research Center are designed to provide a more complete and detailed description of the political landscape, classifying people on the basis of a broad range of value orientations rather than just on the basis of party identification or self-reported political ideology. As in the past, the new typology reveals substantial political and social differences within as well as across the two political parties. It also provides insights into the political and social values of independents, a growing part of the American electorate, but one that is far from unified in terms of values and ideological beliefs.

Some of the groups in this year’s typology share characteristics with those identified in previous typologies, reflecting the continued importance of key ideological positions among some segments of the electorate. Other groups are distinctly new and partly reflect the influx of younger voters and racial and ethnic minorities who are now influencing the political alignments. As new groups have emerged and the political and economic climate has changed, some groups identified in previous typologies have disappeared entirely.

An Evolving Landscape: The 2011 Typology

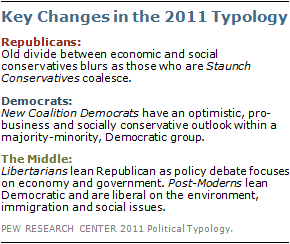

Perhaps the most notable change in the new typology is the realignment of the political right over the past six years. In 2005, and most previous studies, the Republican coalition was a sometimes uneasy mix of two main groups – one characterized by its economic conservatism and another by its social conservatism. Six years ago, there also was a third Republican group, “Pro-Government Conservatives,” who were critical to George W. Bush’s reelection in 2004. Pro-Government Conservatives were aligned with the other Republican groups on foreign policy and social issues. As their name suggests, they also were supporters of government programs, including the social safety net, environmental protection, and regulation of business.

Today, the classic division between economic and social conservatives is blurred, as Americans who are deeply conservative across the board have coalesced into a single, highly activated group of Staunch Conservatives. A second group of Main Street Republicans has nearly as strong a partisan identity, but is less politically active, and differs from the Staunch Conservatives on key dimensions such as business and the environment. A new Republican-oriented group of Libertarians believe in the same economically conservative principles as the Staunch Conservatives, but its members differ when it comes to social issues, where they are very secular. Disaffecteds, another GOP-leaning group, has been a part of Pew Research typologies since 1987.

The left side of the political spectrum has also seen realignment, most notably because of the diversity of views among minorities and younger Americans, who represent the growing segment of the Democratic Party’s base. As was the case in 2005, the foundation of the Democratic Party’s base is composed of Solid Liberals, who are mostly white and liberal across the board, and Hard-Pressed Democrats, a group that includes many minorities and whose members have generally lower incomes and more socially conservative views.

Coupled with these, past typology studies found a third group of socially conservative Democrats who were older, mostly white, and held traditional social values while supporting New Deal-type policies. This year, however, the balance has tipped toward a group of New Coalition Democrats, who are defined not only by their social conservatism, but by their ethnic diversity and optimism in the face of the recession. The appearance of the New Coalition Democrats is further evidence that while African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans continue to overwhelmingly align with the Democratic Party, they are hardly unified blocks in terms of ideology and values.

A group of independently-minded Post-Moderns, who have voted overwhelmingly Democratic in the past two elections, are the youngest of all the typology groups. This mostly secular group agrees with Solid Liberals on social issues, immigration and the environment, but is not engaged with the traditional liberal rallying cries of the New Deal or Great Society. Instead, this group tends to be more supportive of Wall Street and business interests, and skeptical of broad-based social justice programs aimed at helping African-Americans and the poor.

More Independent, But Not More Moderate

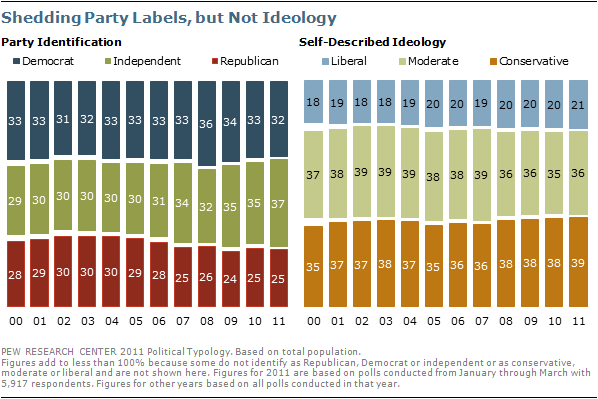

In recent years, the public has become increasingly averse to partisan labels. Pew Research Center polling over the first quarter of 2011 finds 37% of Americans identifying as independents, up from 30% in 2005 and 35% last year. Over the past 70 years, the only other time that independent identification reached a similar level was in 1992, the year when Ross Perot was a popular independent presidential candidate.

The growing rejection of partisan identification does not imply a trend toward political moderation, however. In fact, the number of people describing their political ideology as moderate has, if anything, been dropping. So far in 2011, 36% say they are moderate politically, which is unchanged from 2008 but slightly lower than in 2005 (38%).

Meanwhile, conservatives outnumber liberals by nearly two-to-one. The number identifying as conservative has edged up to 39% this year from 35% in 2005, while the number of liberals is little changed (21% now, 20% then).

Party Affiliation and the Typology Groups

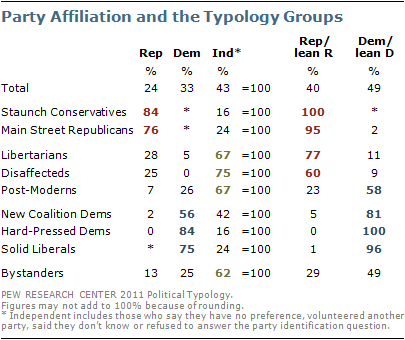

The new political typology finds two groups that are clearly Republican in their political orientation, three that are predominantly Democratic, and – reflecting the growing number of independents – four in which majorities eschew party labels. Within this broad political center are two Republican-leaning groups and one Democratic-leaning group, along with the politically uninvolved Bystanders.

On the right, Staunch Conservatives and Main Street Republicans overwhelmingly identify as Republicans. Similarly, on the left large majorities of Solid Liberals and Hard-Pressed Democrats consider themselves Democrats. While a majority of New Coalition Democrats identify with the Democratic Party, many consider themselves independents (though most say they lean toward the Democratic Party).

The middle is far more diverse. Although majorities in all of these groups identify as political independents, 77% of Libertarians and 60% of Disaffecteds lean to the GOP while 58% of Post-M0derns lean to the Democratic Party. The politically disengaged Bystanders – who do not vote or follow politics – lean somewhat to the Democratic Party.

Lessons from 2008 and 2010

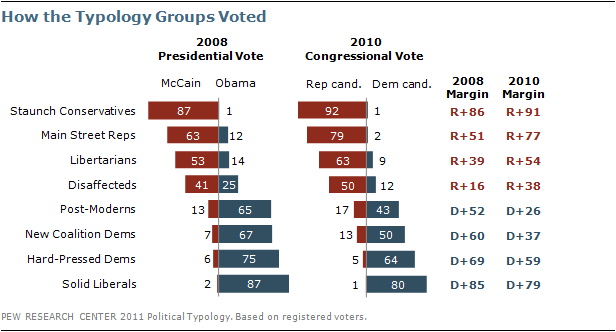

The voting behavior of the typology groups in the past two election cycles is consistent with each group’s underlying partisan leanings, but also reveals how tenuously each party’s winning coalition depends on candidates and circumstances.

Barack Obama won the 2008 presidential election by solidifying the backing of not only the Solid Liberal and Hard-Pressed Democratic groups, but also by activating and appealing to New Coalition Democrats and Post-Moderns. Fully 87% of Obama’s votes came from these four key coalition sources, though he attracted a respectable 13% of his overall vote total by reaching out to Disaffecteds, Libertarians and Main Street Republicans as well. (Obama won virtually no support from Staunch Conservatives.)

The 2010 midterms revealed the fragility of this electoral base. While both Solid Liberals and Hard-Pressed Democrats remained solidly behind Democratic congressional candidates in 2010, support slipped substantially among New Coalition Democrats and Post-Moderns – not because Republicans made overwhelming gains in these groups, but because their turnout dropped so substantially. Where two-thirds of New Coalition Democrats came out to vote for Obama in 2008, just 50% came out to back Democrats in 2010. The drop-off in the Democratic vote was even more severe among Post-Moderns, 65% of whom backed Obama, but just 43% of whom came to the polls for Democrats in 2010.

Equally important was the shoring up of center groups by the GOP in 2010. In particular, Disaffecteds favored McCain over Obama by a 16-point margin (41% to 25%) in 2008, but backed Republicans by nearly five-to-one (50% to 12%) in 2010. Libertarians, too, were more likely to back GOP candidates in 2010 (63%), than McCain in 2008 (53%).

And while Staunch Conservatives voted solidly Republican in both years, the 2010 midterm was a far more crystallizing election for Main Street Republicans, with 79% backing Republican Congressional candidates compared with the 63% who came out to vote for McCain two years earlier. Overall, 89% of Republican votes cast in 2010 came from the four Republican-oriented voting blocs.

Looking toward 2012, these past two election cycles serve as a model of what the core party coalitions look like. The following sections will show how challenging the maintenance of these winning coalitions will be for political leaders on both sides of the aisle.

Creating the Typology

The 2011 typology divides the public into eight politically engaged groups, in addition to the Bystanders. These groups are defined by their attitudes toward government and politics and a range of other social, economic and religious beliefs. In addition to partisan affiliation and leaning, the typology is based on nine value orientations, each of which is reflected on a scale derived from two or more questions in the survey. The scales are as follows:

- Government Performance. Views about government waste and efficiency and regulation of business.

- Religion and Morality. Attitudes concerning the importance of religion in people’s lives, whether it is necessary to believe in God to be moral and views about homosexuality.

- Business. Attitudes about the influence of corporations and the profits they make.

- Environmentalism. Opinions on environmental protection and the cost and benefits of environmental laws and regulations.

- Immigration. Views about the impact of immigrants on American culture, jobs and social services.

- Race. Attitudes concerning racial discrimination and whether the country has made changes to give blacks equal rights with whites.

- Social Safety Net. Opinions on the role of government in providing for the poor and needy.

- Foreign Policy Assertiveness. Opinions on the efficacy of military strength vs. diplomacy and the use of force to defeat terrorism.

- Financial Security. Level of satisfaction with current economic status and whether struggling to pay the bills.

These measures are based on broadly oriented values designed to measure a person’s underlying belief about what is right and wrong, acceptable or unacceptable, or what the government should or should not be involved in. The scales are not based on a person’s opinions about political leaders and parties or current issues.