While preventive care and regular health monitoring are essential in maintaining good long-term health and limiting the severity of chronic diseases, more than one in four Hispanics say they received no information regarding health or health care from doctors or health care professionals in the past year. This group includes a wide cross-section of the Hispanic population.

However, medical professionals are not the only ones providing health and medical information. Specific information regarding the importance of preventative care and regular health monitoring as well as the symptoms and treatment of chronic diseases can be delivered through alternate sources. Print and broadcast media, churches, community groups, family and friends, and the Internet are all sources of health and medical information for many Hispanics. Though the survey results do not address the validity or quality of the health information obtained through sources other than medical personnel, results do suggest that the information from these alternative sources has an impact on respondents’ behaviors.

Different sub-groups of Hispanics rely on different types of media. In general, U.S.-born Hispanics and those who have higher levels of education are more likely to get information in English from sources such as television, newspapers, magazines and the Internet. Immigrant Hispanics and those who have lower levels of education rely more on Spanish-language media, including television and print media, for information.

Where Do Hispanics Get Health Care Information?

Respondents were queried as to how much information about health and health care they got from several different sources in the past year. For each potential information source, they could report getting “a lot” of information, “a little” information, or no information at all. Results show that doctors and other medical professionals are the most common source of health and medical information for Hispanics, as they are likely to be for most groups. Nearly a third of Hispanics say they received a lot of health and health care information from doctors or other medical professionals over the past year, and 39 percent say they received a little information.

Seventy-one percent of Latinos received health information from a medical professional in the past year, but 83 percent got health or health care information from the media.

The second most important source of health information is television; 23 percent of Hispanics received a lot of information from TV and 45 percent received a little. Family and friends are next in rank: they supplied a lot of information to 20 percent of Hispanics and a little information to an additional 43 percent.

Radio, newspapers and magazines, and the Internet are also important sources of health care information. Among Hispanics, 40 percent get health care information from the radio, 51 percent get some information from newspapers and magazines, and 35 percent get information from the Internet.

Churches and community organizations are another source of health information for many Hispanics. About one in three Latinos (31 percent) say that they rely on the information they get from their churches and local community groups.

Who Gets Information from the Medical Community?

Hispanic women are more likely than are men to report getting health information from doctors and the medical community in the past year—77 percent report as much, compared with 66 percent of men. Overall, the age differences in receiving any information from medical professionals are not huge, but respondents ages 65 and older are more likely to have gotten a lot of health information from a professional (41 percent) than respondents under age 30 (28 percent).

As is the case with usual health care providers, those who are more educated and more assimilated are more likely to report exposure to the medical system. People with at least some college education are almost 33 percent more likely to have gotten a medical professional’s advice than people lacking a high school diploma. Seventy-nine percent of Latinos who speak primarily English and three-fourths of those who are bilingual report obtaining information from medical providers in the past year, while 62 percent of Spanish-dominant Latinos have done so. Legal status is also correlated with the likelihood of obtaining health advice from a medical professional. Citizens born in the United States or Puerto Rico are most likely to have received medical advice (80 percent) from a professional, followed by naturalized citizens (70 percent), and legal permanent residents (64 percent). Fifty-nine percent of immigrants who are neither naturalized nor legal permanent residents reported obtaining health information from a medical professional.

Respondents of Puerto Rican (80 percent) and Cuban (78 percent) origin are especially likely to have received help from a medical professional in the past year. Conversely, Mexican-origin persons (69 percent) and Central Americans (69 percent) were less likely to report as much.

Who Gets Health Information from the Media?

While most Hispanics look to the medical community for answers to their health care questions, the media, and particularly television, also play a large role in providing health information. This role is especially important for Hispanics who do not typically utilize the health care system. Somewhat more than half (53 percent) of all Hispanics who lack a regular health care provider say they receive at least some information from doctors, but 64 percent of them say they get information from television. In contrast, among Hispanics who do have access to a usual place for their medical care, the relationship reverses: 78 percent say they get health information from the medical community, compared with 70 percent who say they get information from television.

This pattern is similar for Hispanics with and without health insurance. While 78 percent of Hispanics who have medical insurance get some information from doctors and other health care professionals, 69 percent say they get information from television. Conversely, while 59 percent of the uninsured say they get information from doctors, 68 percent obtain health information from television.

Television is the most pervasive media outlet, in terms of disseminating health information; 68 percent of respondents received information from television in the past year.

The use of television for health information is somewhat more prevalent among the foreign born and the less assimilated. Twenty-six percent of the foreign born report obtaining a lot of health information from this source in the past year, as did 19 percent of the native born. Twenty-seven percent of Spanish-dominant respondents reported obtaining a lot of information from television, compared with 18 percent of English-dominant respondents.

Radio also is an important source of health care information for Hispanics. Radio’s role as an information source is roughly similar for Hispanics with a health care provider (39 percent) and those without one (42 percent). Likewise for Hispanics who have health insurance and those who do not—40 percent in both cases obtain health information from the radio.

Like television, radio as an information source is somewhat skewed toward immigrants and those whose primary language is Spanish. Thirty-five percent of English-dominant respondents get health information from the radio, compared with 42 percent of Spanish-dominant respondents. The results are similar when considering nativity. Thirty-five percent of the native born use the radio as a source for health information, compared with 42 percent of the foreign born.

More than half of all Hispanics say they received a lot of information (14 percent) or a little information (37 percent) from print sources. Higher education levels, being native born and assimilation are all associated with higher likelihoods of retrieving health information from these print media. Forty-one percent of Latinos with less than a high school diploma report getting information from newspapers or magazines, compared with 63 percent of people with at least some college education. Fifty-seven percent of the native born use print media, as do 47 percent of the foreign born. While 56 percent of English-dominant and bilingual Latinos obtained at least some health information from these sources, the share drops to 42 percent among Spanish-dominant Latinos.

Youth, education, nativity and assimilation are all strongly linked to Internet usage for Latinos in general,15 and to the likelihood of using the Internet for health information in particular. Younger Hispanics use the Internet more than older Hispanics—42 percent of those ages 18 to 29 say they get information from the Internet, compared with 14 percent of those ages 65 and older. The educational differences in the likelihood of getting health care information from the Internet are stark. While only 16 percent of Hispanics with less than a high school diploma and 36 percent of those with a high school diploma get information on health issues from the Internet, 63 percent of Hispanics who have at least some college education say that they get a lot or a little information from the Internet. Hispanics born in the United States are twice as likely as are immigrants to get health care information from the Internet—52 percent versus 25 percent. English dominance, too, is strongly associated with using the Internet for health information; 53 percent of the English-dominant do so, compared with 17 percent of the Spanish-dominant.

Who Gets Health Care Information from the Media in Spanish, and Who Gets it in English?

Among Hispanics who receive any health-related information from television, 40 percent get that information from only Spanish-language television stations, 32 percent from a mix of Spanish and English-language stations and 28 percent from only English-language stations. Similarly, among the Hispanics who use radio to obtain any of their health care information, 47 percent rely on Spanish-language radio stations, 26 percent listen to Spanish and English-language stations and 27 percent rely on only English stations.

More than half of respondents who get information from television or radio report getting that information in Spanish, or in a mix of Spanish and English.

Women are more likely than men to get their health information in Spanish (44 percent versus 36 percent for television viewers, and 53 percent versus 43 percent for radio listeners). Age is also correlated with obtaining health information from Spanish-language broadcasts. Thirty-eight percent of respondents younger than 30, and 48 percent of respondents ages 65 and older who got health information from television got it in Spanish. Similarly for radio listeners, 44 percent of those ages 18 to 29 and 54 percent of those ages 65 or older received their health information in Spanish.

Among those who watch television and those who listen to the radio, there is a strong association between educational levels and language use. In both cases, people with less than a high school diploma were more likely to get their information in Spanish (56 percent for television, 64 percent for radio) compared to those with at least some college education (17 percent for television, 20 percent for radio).

Of course, being native born and assimilated are associated with lower likelihoods of obtaining broadcast media health information in Spanish.

Most frequently, the information obtained from the Internet was solely in English (58 percent). However, 13 percent of respondents reported obtaining only Spanish-language Internet health care information. Twenty-nine percent of respondents got Internet health information in both English and Spanish. The pattern is similar for newspapers and magazines. Hispanics who get some information from print media are most likely to read English-language newspapers and magazines (43 percent), though 27 percent read Spanish-only publications and 29 percent got health information from both Spanish and English publications.

Health Care Information from Social Networks

More than 60 percent of Hispanics report that they received health information from their family and friends in the past year: 19 percent got a lot of information that way, and 43 percent got a little. Immigrants are less likely to get information from family and friends (59 percent) than are native-born Hispanics (71 percent), plausibly because they have smaller networks of family and friends in the United States. Younger Latinos are more likely to get information from family and friends than are older Latinos—those ages 18 to 29 are 25 percentage points more likely to get information from family and friends than are Hispanics ages 65 and older.

Seventy-nine percent of respondents who received health or health care information from the media acted upon that information.

Churches and community groups also play a role in providing health and health care information to Hispanics. Roughly 9 percent of Hispanics say they receive a lot of information from churches and community groups, and 22 percent say they receive a little information from these sources. There are few notable differences among demographic groups here. Around one-third of Hispanics with a high school education or less get information from churches and community groups, compared with 26 percent of people without at least some college education. Another group that relies more heavily on churches and community groups are Spanish-dominant respondents; 34 percent report obtaining health information from these sources, compared with 25 percent of English-dominant Latinos.

As such, it’s no surprise that the information that Hispanics received from churches or community groups was more likely to be in Spanish only (49 percent) or in both Spanish and English (31 percent) than only in English (19 percent). This is similar to the language of information obtained from the radio and quite distinct from that of information obtained from the Internet, newspapers and magazines.

The Impact of the Media

Though the survey data do not allow for an evaluation of the appropriateness of the behavioral changes that result from media exposure to health information, results clearly indicate that alternative channels of health information have an effect on Latinos’ behavior.

The media’s impact is strongest in producing reported changes in how Hispanics think about diet and exercise. Almost two-thirds of all Hispanics who received health and health care information last year from broadcast or print media, or from the Internet, say that what they learned changed the way they think about diet or exercise.

Younger Latinos and women are more receptive to these types of changes than are older Hispanics or men. And while immigrants (69 percent) are more likely to say that health information from the television, radio, newspapers or the Internet led them to change how they think about diet and exercise, a majority of native-born Hispanics (56 percent) also report making changes in how they think about nutrition and physical activity because of what they learned from the media.

Health information provided by the media led 57 percent of Hispanics to ask a doctor or medical professional new questions. Six in 10 Hispanics who have a usual provider say this. So do nearly half of all Hispanics who do not have a usual provider. Latinos whose primary language is Spanish are more likely to ask new questions to health care professionals as a result of media coverage than are English speakers, pointing again to the important role played by the Spanish-language media.

The media even influence how some 41 percent of Hispanics make decisions on how to treat an illness or medical condition. Here, demographic differences among Latinos are not great. Both those who have a usual provider (42 percent) and those who do not (38 percent) are nearly as likely to say that what they learned from the media affected how they think about treatment.

According to the American Diabetes Association, millions of Americans are unaware that they have diabetes. Although there is no cure for diabetes, people who know they have the disease often can keep it under control, and reduce the risk of serious side effects or death, through treatment that includes diet and medication.

Three-quarters (76 percent) of Hispanics know that there are effective treatments for diabetes that reduce the chances of death or serious side effects; the same share correctly say there is no medicine or treatment “that can permanently fix it.” A slightly lower share (72 percent) of Hispanics is aware that maintaining a healthy weight is more helpful in preventing diabetes than avoiding all sugar. Seven in 10 Latinos (71 percent) say correctly that even people without a family history of diabetes have a risk of developing it.

These findings emerge from a battery of eight questions testing basic knowledge about the causes, symptoms and treatment of diabetes. Although most Latinos do reasonably well (58 percent answered at least six questions correctly), a sizeable minority faltered on the test with nearly a third (32 percent) giving three to five correct answers and 10 percent scoring even lower.

Diabetes Knowledge Battery Scoring

High: Respondents answered at least six out of eight questions correctly.

Medium: Respondents answered three to five questions correctly.

Low: Respondents answered two or fewer questions correctly.

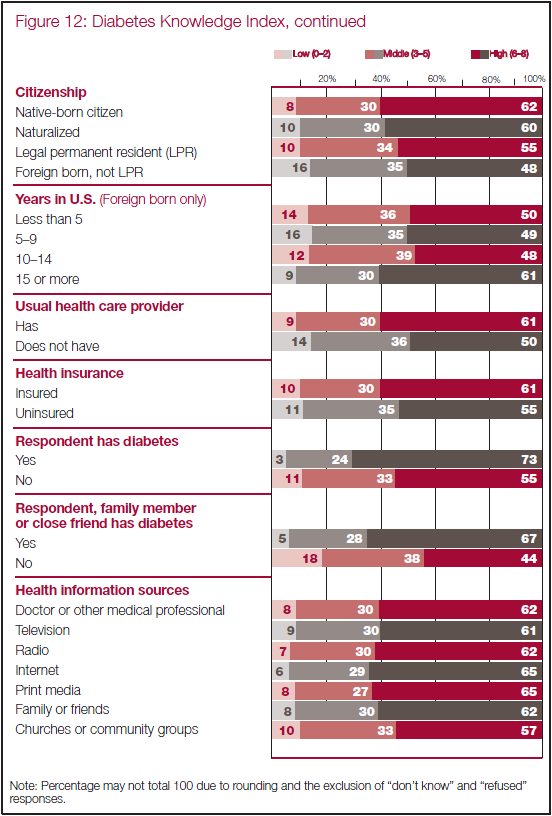

Among the less knowledgeable Hispanics are men, Spanish speakers and Latinos who are foreign born. The best-informed Hispanics about diabetes are those with at least some college education, or with high levels of assimilation—U.S. citizens and long-term immigrants. Hispanics who have been diagnosed with diabetes score higher on the knowledge test than other Latinos, but a notable share (27 percent) answered at least three of the eight questions wrong. Having health insurance and a regular health care provider are both associated with more diabetes knowledge but they do not guarantee being well-informed. Similarly, obtaining health information from medical personnel is associated with higher levels of knowledge but certainly does not guarantee them. Obtaining health information from some other sources is also associated with higher levels of diabetes knowledge. Respondents who report obtaining health information from family and friends and from print media, in particular, score better on the battery of diabetes knowledge questions.

Knowledge Differences by Demographic Group

There are notable differences by demographic characteristic in which Hispanics score high (six to eight correct answers), medium (three to five correct answers) or low (two or fewer correct answers) on a battery of eight questions testing basic diabetes knowledge.

About two-thirds of women (65 percent) correctly answer six or more questions, compared with half (51 percent) of men. Men also are more likely to get a low score, 13 percent compared with 7 percent of women.

The youngest and oldest Latinos know less than those in the middle: 48 percent of those ages 18–29 and 65 and older score well, compared with substantial majorities of those ages 30 to 49 (63 percent) and 50 to 64 (68 percent). Among the oldest Hispanics, 15 percent score low, a larger share than for other age groups.

There are differences across several demographic measures that point to greater knowledge by more assimilated, established Hispanics.

Looking at differences by education level, 13 percent of Latinos who did not complete high school score low on diabetes knowledge, compared with 6 percent of those with at least some college education. Although half of Latinos without a high school diploma score high, that compares with 70 percent of those with at least some college education.

Nativity and assimilation are associated with higher levels of diabetes knowledge.

Similarly, U.S.-born Hispanics are more likely to score high on diabetes knowledge (62 percent) than those who are foreign born or Puerto Rican (56 percent). When responses are analyzed by citizenship status, naturalized citizens are more likely to score high (60 percent) than are legal permanent residents (55 percent) or immigrants who are neither citizens nor legal permanent residents (48 percent). Among long-term immigrants, those who have been in the country for 15 years or more, 61 percent score high, compared with about half of shorter-term immigrants.

Examining differences by national origin, at least 14 percent of persons of Cuban, South American and Central American origin score low on diabetes knowledge, which is a larger share than for other groups. Central Americans (46 percent) and South Americans (47 percent) also have smaller shares of the highest-scoring respondents.

Knowledge Differences by Insurance Status and Health Care Access

Hispanics with health insurance are somewhat more likely to score high than those without insurance (61 percent versus 55 percent), but they are no less likely to get a low diabetes knowledge score than respondents with no insurance. There are, however, differences between Hispanics with and without a usual source of care: 61 percent of those with a usual source score high, compared with 50 percent of those who have no usual provider. A higher share of Latinos (14 percent) with no usual source of care scores low, as compared with Hispanics who do have a usual source of care (9 percent). Among those with a usual provider, the type of place where care is obtained also factors into diabetes knowledge. Respondents who visit a doctor regularly score better on diabetes knowledge questions than respondents who primarily visit clinics for their care; 65 percent score high, as compared with 57 percent of respondents who frequent clinics.

Knowledge Differences by Sources of Information

Latinos who get a lot of health information from doctors are more likely to score high (65 percent) on diabetes knowledge than those who get little (59 percent) or no information (49 percent) from doctors. Those who get a lot of information from newspapers and magazines also are more likely to score high (69 percent) than those who get no information from those sources (50 percent). Those who get a lot of information from family and friends or the Internet also are more likely to score higher (62 percent and 71 percent, respectively) than those who do not (51 percent and 54 percent).

However, the gap in persons scoring high on diabetes knowledge is smaller when comparing respondents who report getting a lot of health information from television (59 percent) with those who report getting no health information from television (52 percent). The same is true for radio: 60 percent of those who get a lot of health information from radio score high, compared with 55 percent who get no health information from radio. Among those who get a lot of information from churches or community groups, a larger share scores low (58 percent) than high (52 percent).*

When these responses are analyzed another way—comparing people who get at least some health information from any source with those obtaining no health information from any source—getting information is associated with better knowledge scores. One in four Hispanics who get no health information score low on diabetes knowledge, compared with one in 11 who get at least some information. Four in 10 of those who get no health information score high on diabetes knowledge, compared with six in 10 of those who get at least some information from any source.

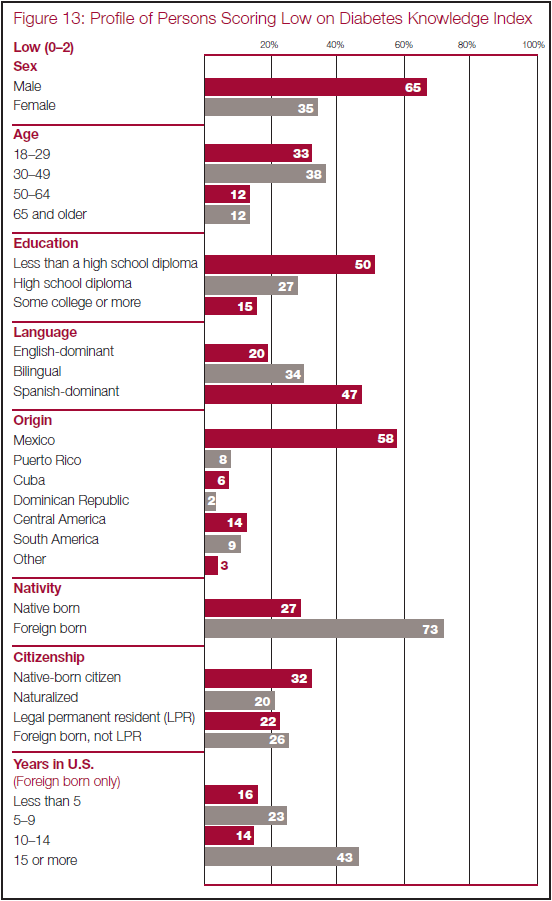

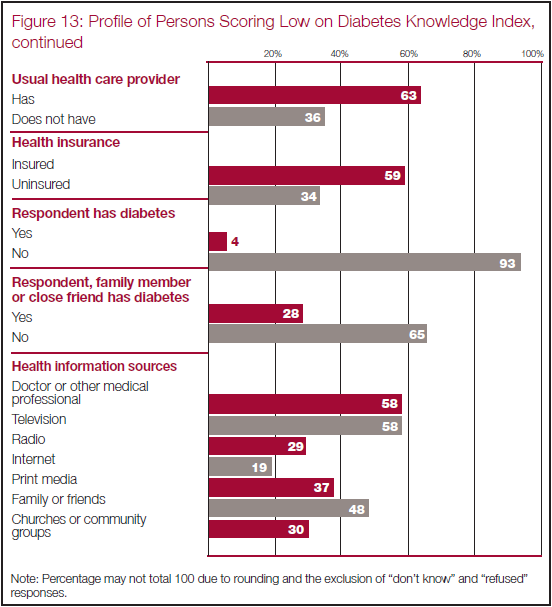

Composition of the Low-Scoring Group

This section will look at the survey data on diabetes knowledge from another perspective: The makeup of the low-scoring group. Although less educated and less assimilated Hispanics generally score lower on a test of diabetes knowledge, the least knowledgeable group also includes a notable share of higher-status Latinos.

Nearly two-thirds of the low-scoring group (65 percent) are men. A third of the low scorers are ages 18–29, a slightly higher share (38 percent) are ages 30–49, 12 percent are ages 50–64, and the remaining 12 percent are 65 years and older.

Half of the group that knows little about diabetes consists of Hispanics who did not complete high school. High school graduates account for 27 percent and Latinos with at least some college education make up 15 percent.

The majority of Hispanics scoring low on the diabetes knowledge index have health insurance or a usual health care provider.

Foreign-born Hispanics account for more than seven in 10 of the low-scoring group. The foreign-born low-scoring group is split nearly evenly into citizens (20 percent of all low scorers), legal permanent residents (22 percent) and persons lacking citizenship or legal permanent residency (26 percent). Although Spanish speakers account for nearly half of low scorers (47 percent), one in five are English-dominant and one in three are bilingual.

Most Hispanics who score low on the knowledge test about diabetes have health insurance (59 percent), and a usual place to go for medical care (63 percent). About six in 10 of the low-scoring group (58 percent) say they get health information from medical professionals.

Diabetics’ Knowledge of Diabetes

Diabetics are more likely to know the basic facts about their condition than the general population does, but not all diabetics are well-informed: 73 percent score high on the knowledge test, 24 percent get a medium score and 3 percent get a low score.

Generally, diabetics have the same pattern of answers as the general population, but at higher levels of knowledge. For example, they are more likely to know that blurry vision is a symptom (82 percent) than increased fatigue (69 percent). However, diabetics are no more likely than all Hispanics (76 percent) to know that effective treatments are available to reduce the chances of blindness, death or other serious complications. Nor are they more likely to know that maintaining a healthy weight is a better way to prevent diabetes than avoiding sugar intake (71 percent of diabetics are aware of this, as compared with 72 percent of non-diabetics).

With diabetics, as in the general population, the most educated and established Hispanics score the highest on a test of knowledge about diabetes. Eighty-six percent of diabetic Hispanics with at least some college education score high on the knowledge battery, compared with 71 percent of people lacking a high school diploma, and diabetics with regular care providers are more likely to score high (75 percent) than those without a usual place for care (66 percent).