Learning about family history can be a challenge for Black Americans. Because of slavery, it is often difficult for them to trace their ancestry prior to the 1870 census. Records of the enslaved are often handwritten, poorly maintained, or simply lost of over time. In light of this, the survey asked Black Americans to share what they know of their family and ancestral histories. It also asked Black Americans about the ways they learned about their family’s stories and backgrounds.

How Black Americans learn about their family history

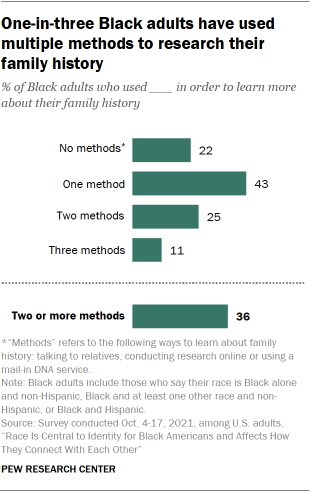

Black Americans were asked if they had done any of the following to learn about their family history: speaking to their relatives, conducting research online, or using a mail-in DNA service such as AncestryDNA or 23andMe. Overall, 43% of Black adults used at least one of these methods, 25% used two, 11% used all three and 22% did not use any.

Black immigrants (31%) were about as likely as U.S.-born Black adults (36%) to have done two or more of these things to research their family history. Black adults for whom being Black is very or extremely important (37%) were also about as likely as those for whom Blackness is less important (31%) to have used two or more methods.

However, multiracial Black adults (51%) and Black Hispanic adults (47%) were more likely than non-Hispanic Black adults (34%) to say they had used two or more methods to research their family history. In fact, 44% of non-Hispanic Black adults only used one method. Among non-Hispanic Black adults who only used one method, 96% spoke to relatives about their family’s history. Of the three methods asked about, multiracial Black adults and Black Hispanic adults were also most likely to say they spoke to their families.

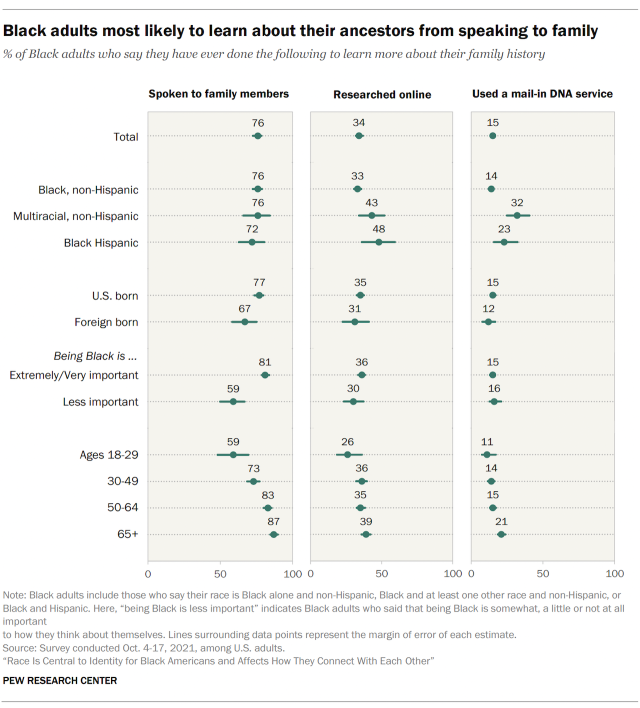

Speaking with relatives to learn about family history

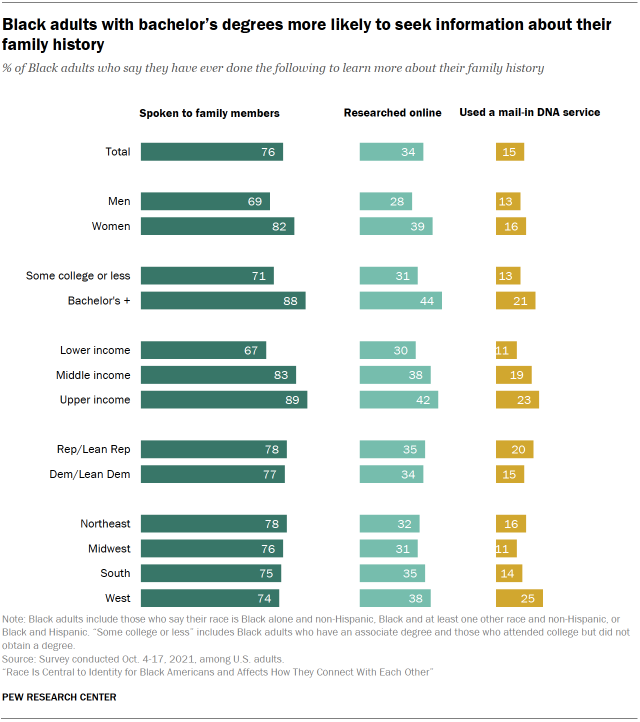

Roughly three-quarters (76%) of Black Americans say they have spoken with their relatives to learn about their family history. Black adults who were born in the United States (77%) are more likely to say they have done this than those born outside the U.S. (67%). Meanwhile, Black adults who are non-Hispanic (76%), multiracial (76%) or Hispanic (72%) are all about as likely to speak to their families to learn about their family’s history. Black adults for whom being Black is a significant part of their personal identity (81%) were more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (59%) to say they have spoken to their relatives about family history.

Black women (82%) were more likely than Black men (69%) to speak with their families about their ancestors. Black adults ages 65 and older (87%) were the most likely of the age groups studied to have discussed this history with their families, while those under 30 were least likely to have done this, though more than half have done so. Moreover, the share of college-educated Black adults (88%) who have spoken to their families about this is higher than the share of Black adults with lower levels of education (71%). Black adults with middle (83%) and upper incomes (89%) are more likely to have had these discussions than those with lower incomes (67%).

Going online or using a mail-in DNA service to learn about family history

Overall, Black adults are less likely to go online to research their family history or use a mail-in DNA service to learn about it than to talk with family. About a third of Black adults (34%) say they have gone online to conduct family history research, while just 15% say they have used a mail-in DNA service.

Many of the same groups that are more likely to talk with relatives about their family history are also more likely to have done online family history research or used a mail-in DNA service to learn about family history, but there are a few exceptions. U.S.-born (35%) and foreign-born Black adults (31%) are equally likely to have conducted family research online, a different pattern from that for speaking with family about family history.

In another departure, Black Hispanic adults (48%) are more likely than non-Hispanic Black adults (33%) to have gone online to do family history research. Meanwhile, Black adults who identify as multiracial (32%) are more likely than non-Hispanic Black adults (14%) to have used a mail-in DNA service to learn about their family’s history. Black Hispanic adults were in between the two groups, with 23% reporting that they used a DNA service to explore family history.

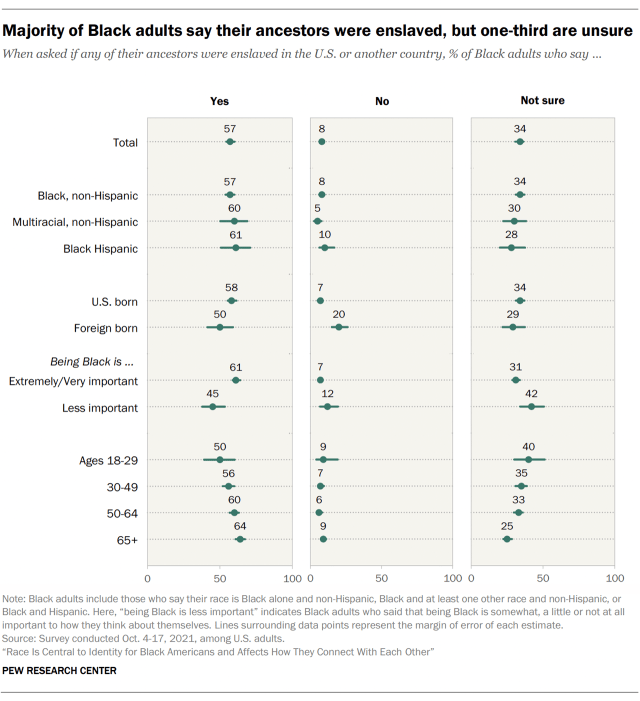

Most Black adults say their ancestors were enslaved, but some are not sure

When it comes to knowledge of their family’s history with slavery, nearly six-in-ten Black adults (57%) say their ancestors were enslaved. About four-in-ten (41%) report they were enslaved in the United States. Only 5% say their ancestors were solely enslaved outside the United States, while 11% say their ancestors were enslaved both in the U.S. and in another country.

However, not all Black Americans are sure whether their ancestors were enslaved, and some say their ancestors were not enslaved. About one-third (34%) say they are not sure if their ancestors were enslaved, while 8% say their ancestors were not enslaved. Black adults born in the United States (55%) are much more likely to say their ancestors were enslaved completely or partially in the U.S. than Black immigrants (21%).

Conversely, Black immigrants (29%) were much more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts (3%) to say their ancestors were only enslaved outside the U.S. About three-in-ten of both groups are unsure whether their ancestors were enslaved. And while just 7% of U.S.-born Black adults say their ancestors were not enslaved, 20% of immigrant Black adults say the same.

Black adults also differ on this question by ethnicity. Non-Hispanic (52%) and multiracial (57%) Black adults are more likely than Black Hispanic adults (36%) to say that their ancestors were enslaved in the United States, in whole or in part.

Meanwhile, Black Hispanic (25%) adults were more likely than non-Hispanic Black (4%) and multiracial (3%) Black adults to say their ancestors were enslaved in other countries. About 30% in each group report being unsure whether their ancestors were enslaved.

Black adults for whom being Black is a very or extremely important part of their personal identity (61%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (46%) to say their ancestors were enslaved, regardless of geography. Those for whom being Black is very or extremely important are also less likely than their counterparts to report being unsure about this (31% vs. 42%).

As with many aspects of identity and connectedness, age is a key point of difference among Black Americans. Black adults ages 65 and older (64%) are more likely than those under 30 (50%) or those 30 to 49 (56%) to say their ancestors were enslaved (either in the U.S. or abroad). Those 65 and older are also less likely than every other age group to be unsure about their family’s history with slavery.

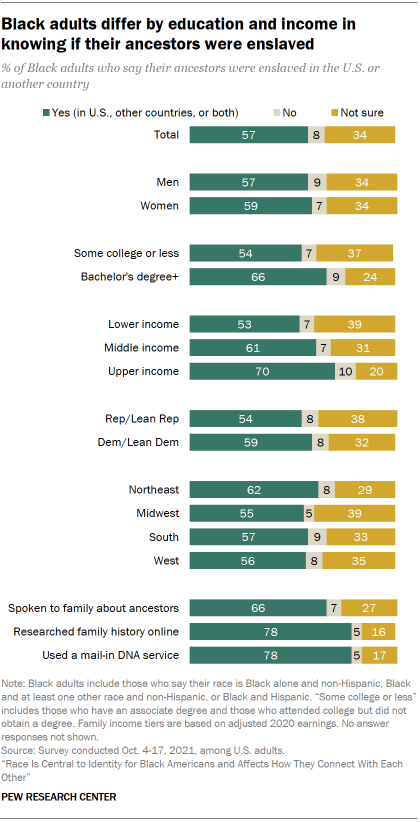

Education and income also yield differences on this question. College-educated Black Americans (66%) are more likely than those with lower levels of education (54%) to report that their ancestors were enslaved. Among Black adults with less than a bachelor’s degree, 37% say they are uncertain about whether their ancestors were enslaved. Black adults with upper incomes (70%) are more likely than those with middle (61%) and lower incomes (53%) to say their ancestors were enslaved. About four-in-ten Black adults with lower incomes (39%) report being unsure about this fact.

There are very few differences by region on this question. Black adults who live in the South (57%) are no more likely than those living in the Northeast (62%), Midwest (55%) or West (56%) to say their ancestors were enslaved. However, Black adults who live in the Northeast (13%) are more likely than those living in the South (4%), Midwest (3%) or West (5%) to say their ancestors had been enslaved outside of the United States. Black adults living in the Midwest (39%) are more likely than those living in the Northeast to say they are uncertain about whether their ancestors had been enslaved.

Black adults who had conducted online research (78%) or used a mail-in DNA service (78%) to learn about their family history were more likely than those who had spoken to their relatives for the same purpose (66%) to say their ancestors were enslaved. Among Black adults who had not used any of these methods to research their family history, only 26% say their ancestors were enslaved.

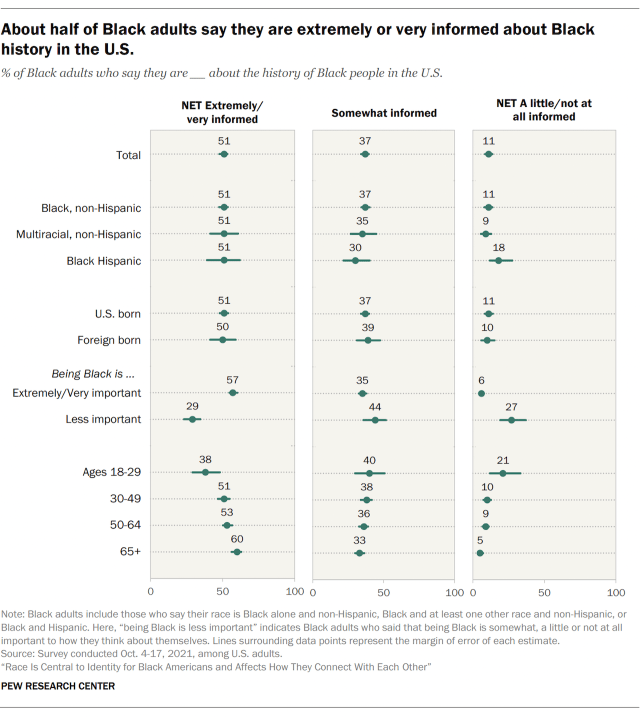

Most Black adults are at least somewhat informed about U.S. Black history

In addition to their family history, we asked Black Americans about their knowledge of racial history. Overall, about half (51%) of Black adults say they are very or extremely informed about the history of Black people in the United States, while 37% say they are somewhat informed. Only 11% say that they are a little informed or not informed at all.

Black adults who were born in the U.S. (51%) are no more likely than Black immigrants (50%) to say they are very or extremely informed. Similarly, Black adults no matter their ethnicity are just as likely to say they are very or extremely informed about Black history.

However, those who say being Black is a significant part of their personal identity (57%) are nearly twice as likely as those for whom being Black is less important (29%) to say they feel very or extremely informed about Black history.

And Black women (37%) are slightly more likely than Black men (30%) to say they are very informed.

Older Black adults are more informed than younger Black adults about Black History. Six-in-ten Black adults ages 65 and older say they are very or extremely informed about Black history, a share that falls to 53% among those ages 50 to 64 and 51% among those 30 to 49. Black adults under 30 (38%) are the least likely of the age groups to say they are very or extremely informed.

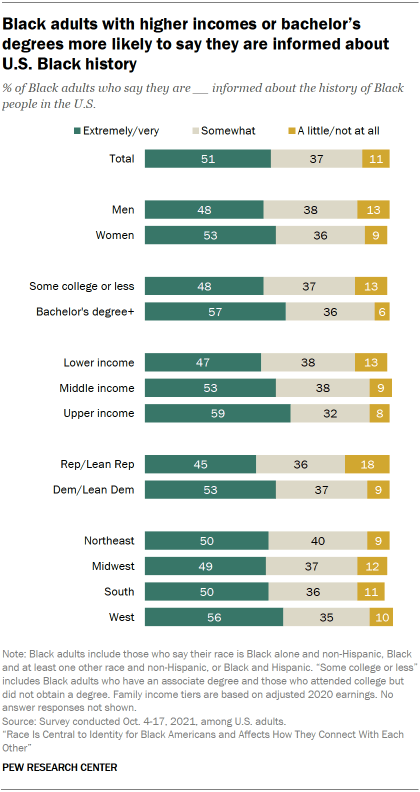

The share of Black college-educated adults who say they are very or extremely informed about Black history (57%) is larger than the share with lower levels of formal education (48%) who say this. Similarly, Black adults with middle (53%) and higher incomes (59%) are more likely to say they are very or extremely informed about Black history than those with lower incomes (47%). There are few differences among Black adults by party or region on this question.

Sources of information about Black history in the United States

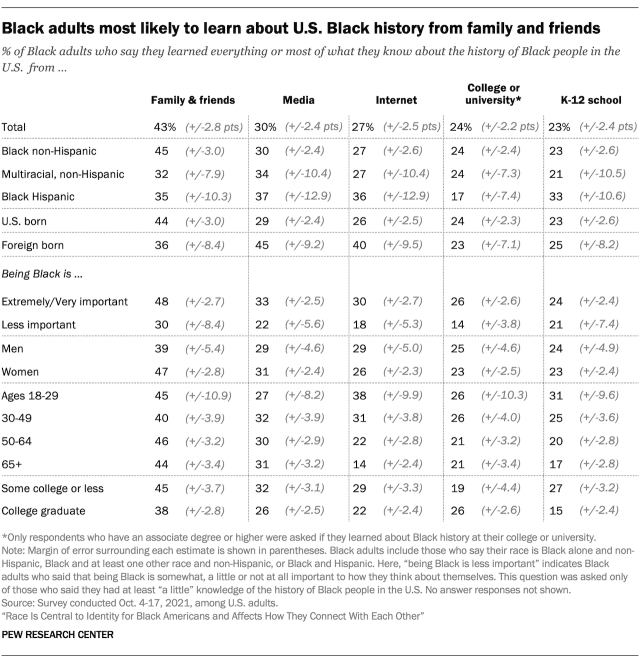

A significant share of Black Americans feel very or extremely informed about U.S. Black history, and many turn to the people closest to them to learn about it. Those who feel at least a little informed about U.S. Black history are more likely to say they learned everything or most things they know about it from family and friends (43%) than from the media (30%), the internet (27%), K-12 schooling, (23%) or college, if they attended (24%). Overall, at least half of Black adults who say they are informed about U.S. Black history learned at least some of what they know about it from each of these sources.

Non-Hispanic Black adults (45%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (32%) to say they learned everything or most things they know about Black history from friends and family. There are few differences between U.S.-born and foreign-born Black adults on this question, although about a quarter of those born outside the U.S. (27%) say they learned little or nothing of what they know about Black history from their families or friends.

Black adults without a college degree (45%) are more likely than those with a degree (38%) to have learned about Black history from family and friends. Relatedly, Black adults with middle incomes (44%) are more likely to have done this than those with upper incomes (37%).

Black adults without a college degree (32%) are also more likely than their degree-holding counterparts (26%) to say that they learned everything or most things they know about Black history from the media, and those with lower and middle incomes (both 31%) are more likely than those with higher incomes (23%) to say the same. More among Black immigrants (45%) than among U.S.-born Black adults (29%) learned everything or most things they know about Black history from the media. These patterns in education, income and nativity hold when it comes to the shares of Black adults who learned everything or most things they know about Black history from the internet.

Black adults under 30 (38%) are more likely than those ages 50 to 64 (22%) and 65 and older (14%) to have learned about Black history on the internet. These age patterns also apply when it comes to educational sources of information. Black adults under 30 (31%) and those 30 to 49 (25%) are both more likely than those ages 50 to 64 (20%) and 65 and older (17%) to say that they learned about Black history in K-12 school.

Much like the patterns above, the share of Black adults without a college degree (27%) who learned everything or most things they know about Black history in K-12 school is larger than the share of

the college educated (15%). Likewise, Black adults with lower (28%) and middle incomes (19%) are more likely than those with upper incomes (14%) to point to their K-12 schooling as their source of their knowledge about U.S. Black history.

Among those who attended college, Black adults who completed a bachelor’s degree (26%) are more likely than those who did not (19%) to say that this education taught them everything or most things they know about Black history.