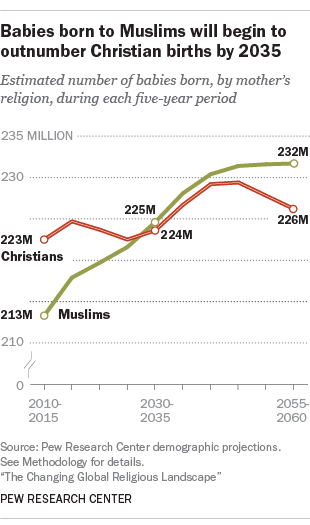

More babies were born to Christian mothers than to members of any other religion in recent years, reflecting Christianity’s continued status as the world’s largest religious group. But this is unlikely to be the case for much longer: Less than 20 years from now, the number of babies born to Muslims is expected to modestly exceed births to Christians, according to new Pew Research Center demographic estimates.

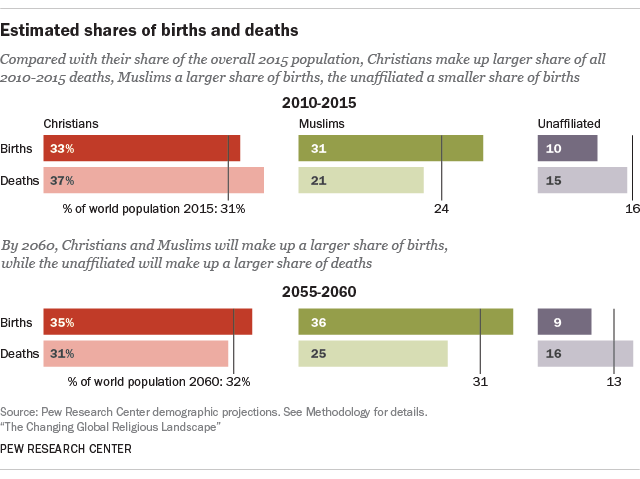

Muslims are projected to be the world’s fastest-growing major religious group in the decades ahead, as Pew Research Center has explained, and signs of this rapid growth already are visible. In the period between 2010 and 2015, births to Muslims made up an estimated 31% of all babies born around the world – far exceeding the Muslim share of people of all ages in 2015 (24%).

The world’s Christian population also has continued to grow, but more modestly. In recent years, 33% of the world’s babies were born to Christians, which is slightly greater than the Christian share of the world’s population in 2015 (31%).

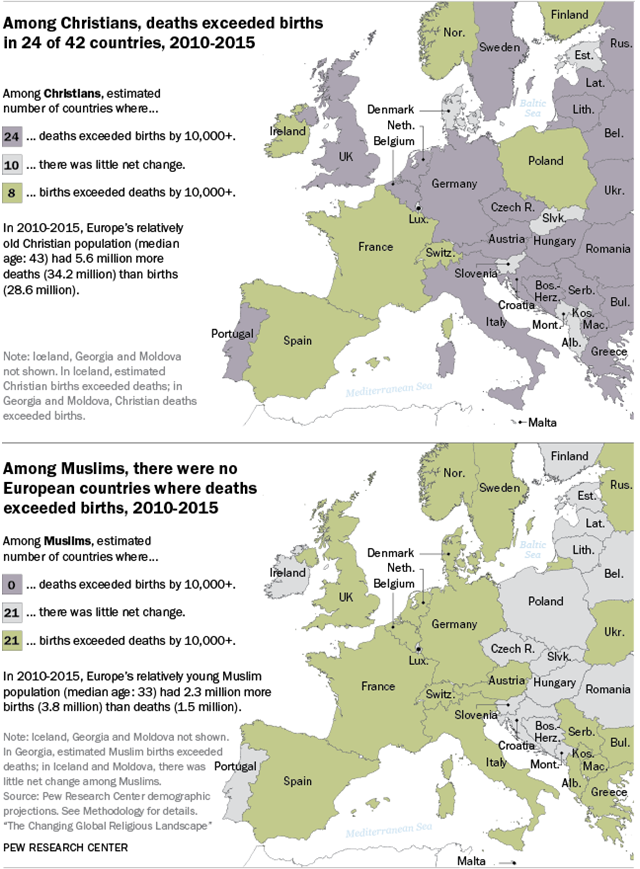

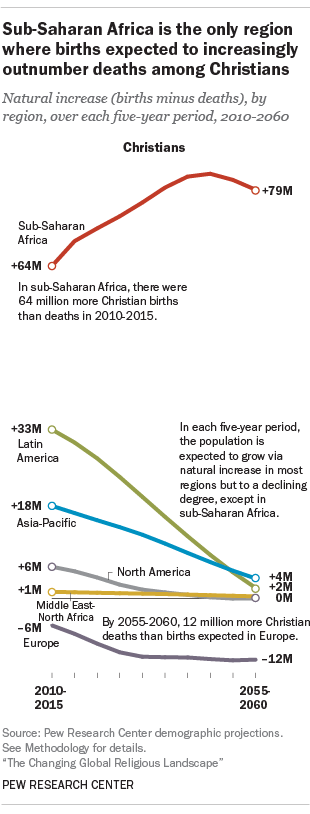

While the relatively young Christian population of a region like sub-Saharan Africa is projected to grow in the decades ahead, the same cannot be said for Christian populations everywhere. Indeed, in recent years, Christians have had a disproportionately large share of the world’s deaths (37%) – in large part because of the relatively advanced age of Christian populations in some places. This is especially true in Europe, where the number of deaths already is estimated to exceed the number of births among Christians. In Germany alone, for example, there were an estimated 1.4 million more Christian deaths than births between 2010 and 2015, a pattern that is expected to continue across much of Europe in the decades ahead.

A note about terminology

The phrase “babies born to Christians” and “Christian births” are used interchangeably in this report to refer to live births to Christian mothers. Parallel language is used for other religious groups (e.g., babies born to Muslims, Muslim births).

This report generally avoids the terms “Christian babies” or “Muslim babies” because that wording could suggest children take on a religion at birth.

The assumption in these estimates and projections is that children tend to inherit their mother’s religious identity (or lack thereof) until young adulthood, when some choose to switch their religious identity. The projection models in this report take into account estimated rates of religious switching (or conversion) into and out of major religious groups in the 70 countries for which such data are available.

Globally, the relatively young population and high fertility rates of Muslims lead to a projection that between 2030 and 2035, there will be slightly more babies born to Muslims (225 million) than to Christians (224 million), even though the total Christian population will still be larger. By the 2055 to 2060 period, the birth gap between the two groups is expected to approach 6 million (232 million births among Muslims vs. 226 million births among Christians).1

In contrast with this baby boom among Muslims, people who do not identify with any religion are experiencing a much different trend. While religiously unaffiliated people currently make up 16% of the global population, only an estimated 10% of the world’s newborns between 2010 and 2015 were born to religiously unaffiliated mothers. This dearth of newborns among the unaffiliated helps explain why religious “nones” (including people who identity as atheist or agnostic, as well as those who have no particular religion) are projected to decline as a share of the world’s population in the coming decades.

By 2055 to 2060, just 9% of all babies will be born to religiously unaffiliated women, while more than seven-in-ten will be born to either Muslims (36%) or Christians (35%).

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center analysis of demographic data. This analysis is based on – and builds on – the same database of more than 2,500 censuses, surveys and population registers used for the 2015 report “The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050.” Both reports share the same demographic projection models, but the figures on births and deaths in this analysis have not been previously released.

In addition, this report provides updated global population estimates, as of 2015, for Christians, Muslims, religious “nones” and adherents of other religious groups. And the population growth projections in this report extend to 2060, a decade further than in the original report.

The projections do not assume that all babies will remain in the religion of their mother. The projections attempt to take religious switching (in all directions) into account, but conversion patterns are complex and varied. In some countries, including the United States, it is fairly common for adults to leave their childhood religion and switch to another faith (or no faith). For example, many people raised in the U.S. as Christians become unaffiliated in adulthood, and vice versa – many people raised without any religion join a religious group later in their lives. But in some other countries, changes in religious identity are rare or even illegal.2

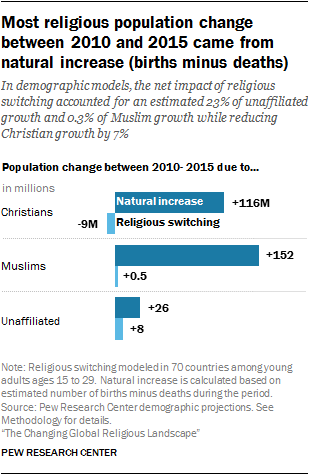

At present, the best available data indicate that the worldwide impact of religious switching alone, absent any other factors, would be a relatively small increase in the number of Muslims, a substantial increase in the number of unaffiliated people, and a substantial decrease in the number of Christians in coming decades. Globally, however, the effects of religious switching are overshadowed by the impact of differences in fertility and mortality. As a result, the unaffiliated are projected to decline as a share of the world’s total population despite the boost they are expected to receive from people leaving Christianity and other religious groups in Europe, North America and some other parts of the world. And the number of Christians is projected to rise, though not as fast as the number of Muslims.

Global population projections, 2015 to 2060

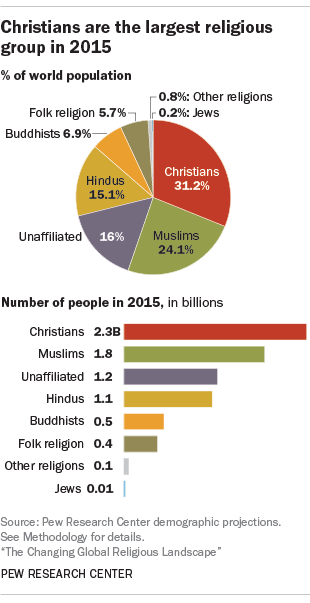

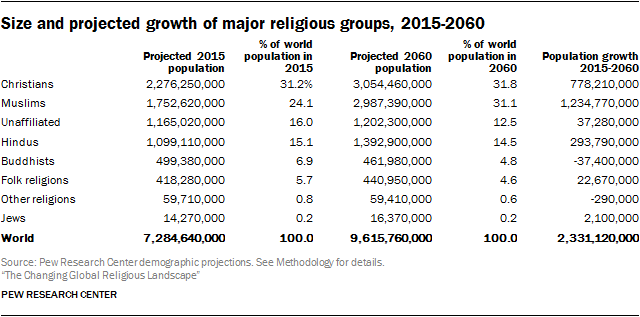

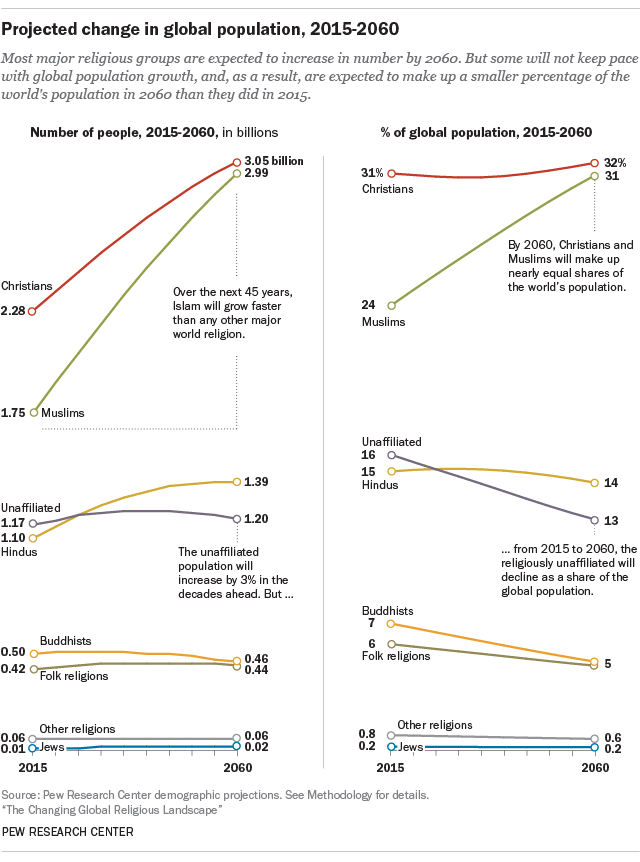

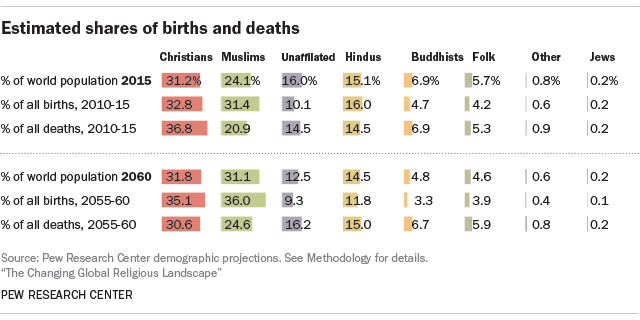

Christians were the largest religious group in the world in 2015, making up nearly a third (31%) of Earth’s 7.3 billion people. Muslims were second, with 1.8 billion people, or 24% of the global population, followed by religious “nones” (16%), Hindus (15%) and Buddhists (7%). Adherents of folk religions, Jews and members of other religions make up smaller shares of the world’s people.

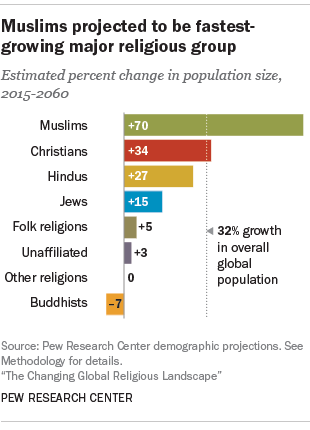

Between 2015 and 2060, the world’s population is expected to increase by 32%, to 9.6 billion. Over that same period, the number of Muslims – the major religious group with the youngest population and the highest fertility – is projected to increase by 70%. The number of Christians is projected to rise by 34%, slightly faster than the global population overall yet far more slowly than Muslims.

As a result, according to Pew Research Center projections, by 2060, the count of Muslims (3.0 billion, or 31% of the population) will near the Christian count (3.1 billion, or 32%).3

Except for Muslims and Christians, all major world religions are projected to make up a smaller percentage of the global population in 2060 than they did in 2015.4 While Hindus, Jews and adherents of folk religions are expected to grow in absolute numbers in the coming decades, none of these groups will keep pace with global population growth.

Worldwide, the number of Hindus is projected to rise by 27%, from 1.1 billion to 1.4 billion, lagging slightly behind the pace of overall population growth. Jews, the smallest religious group for which separate projections were made, are expected to grow by 15%, from 14.3 million in 2015 to 16.4 million worldwide in 2060.5 And adherents of various folk religions – including African traditional religions, Chinese folk religions, Native American religions and Australian aboriginal religions, among others – are projected to increase by 5%, from 418 million to 441 million.

Buddhists, meanwhile, are projected to decline in absolute number, dropping 7% from nearly 500 million in 2015 to 462 million in 2060. Low fertility rates and aging populations in countries such as China, Thailand and Japan are the main demographic reasons for the expected shrinkage in the Buddhist population in the years ahead.

All other religions combined – an umbrella category that includes Baha’is, Jains, Sikhs, Taoists and many smaller faiths – also are projected to decrease slightly in number, from a total of approximately 59.7 million in 2015 to 59.4 million in 2060.6

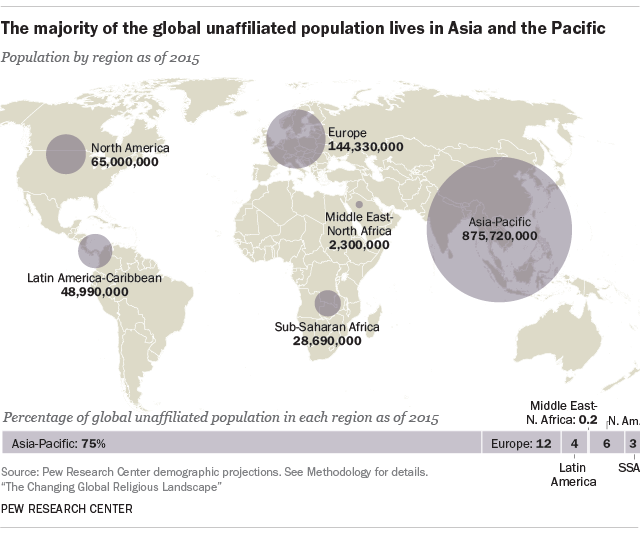

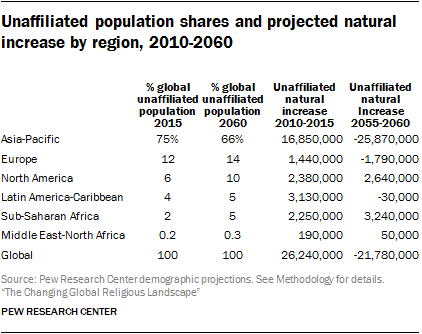

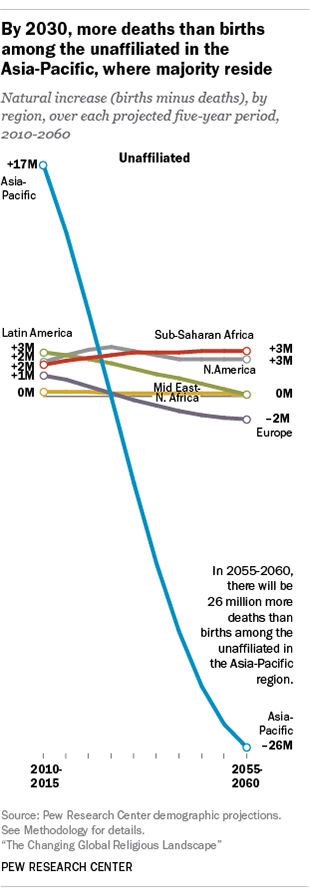

The religiously unaffiliated population is projected to shrink as a percentage of the global population, even though it will increase modestly in absolute number. In 2015, there were slightly fewer than 1.2 billion atheists, agnostics and people who did not identify with any particular religion around the world.7 By 2060, the unaffiliated population is expected to reach 1.2 billion. But as a share of all people in the world, religious “nones” are projected to decline from 16% of the total population in 2015 to 13% in 2060. While the unaffiliated are expected to continue to increase as a share the population in much of Europe and North America, people with no religion will decline as a share of the population in Asia, where 75% of the world’s religious “nones” live.

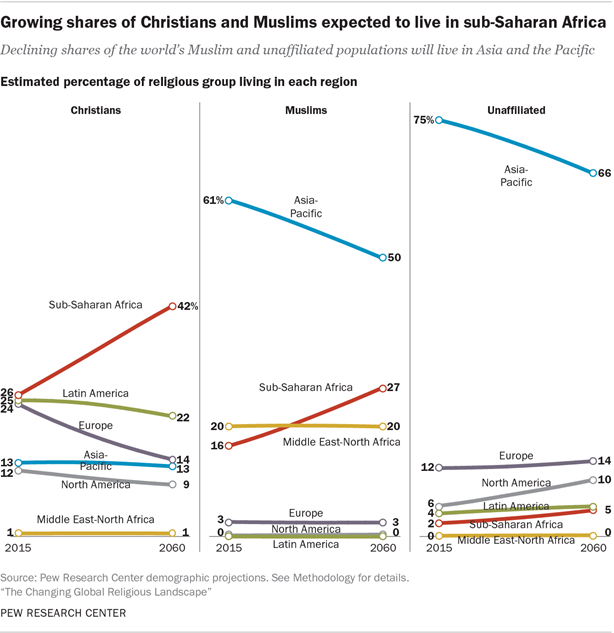

Geographic differences like these play a major role in patterns of religious growth. Indeed, one of the main determinants of future growth is where each group is geographically concentrated today. For example, the religiously unaffiliated population is heavily concentrated in places with aging populations and low fertility, such as China, Japan, Europe and North America. By contrast, religions with many adherents in developing countries – where birth rates are high and infant mortality rates generally have been falling – are likely to grow quickly. Much of the worldwide growth of Islam and Christianity, for example, is expected to take place in sub-Saharan Africa.

Change in where groups are concentrated

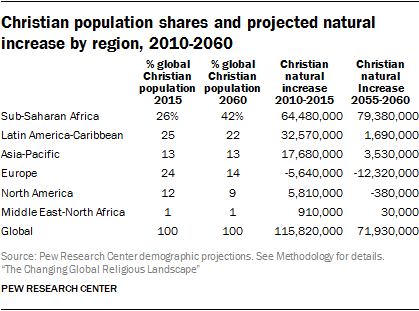

The regional distribution of religious groups is also expected to shift in the coming decades. For example, the share of Christians worldwide who live in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to increase dramatically between 2015 and 2060, from 26% to 42%, due to high fertility in the region. Meanwhile, religious switching and lower fertility will drive down the shares of the global Christian population living in Europe and North America.

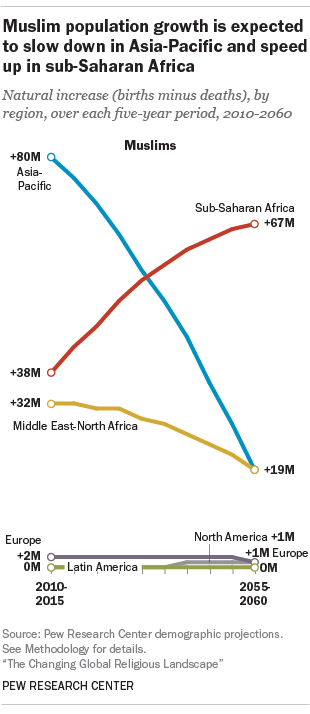

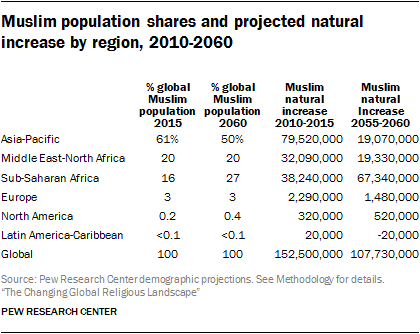

Sub-Saharan Africa is also expected to be home to a growing share of the world’s Muslims. By 2060, 27% of the global Muslim population is projected to be living in the region, up from 16% in 2015. By contrast, the share of Muslims living in the Asia-Pacific region is expected to decline over the period from 61% to 50%. The share of Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa is expected to hold steady at 20%.

As of 2015, three-in-four unaffiliated people live in Asia and the Pacific. But that share is expected to decline to 66% by 2060 due to low fertility and an aging population. At the same time, a growing share of the unaffiliated will live outside of the Asia-Pacific, particularly in Europe and North America. By 2060, 9% of the global unaffiliated population will live in the United States alone, according to the projections.

The vast majority of Hindus and Buddhists (98-99%) will continue to live in the Asia-Pacific region in the next several decades. Most adherents of folk religions, too, will remain in Asia and the Pacific (79% in 2060), although a growing share are expected to live sub-Saharan Africa (7% in 2015 vs. 16% in 2060). Roughly equal shares of the world’s Jews live in Israel (42%) and the United States in 2015 (40%). But, by 2060, over half of all Jews (53%) are projected to live in Israel, while the U.S. is expected to have a smaller share (32%).

Age and fertility are major factors behind growth of religious groups

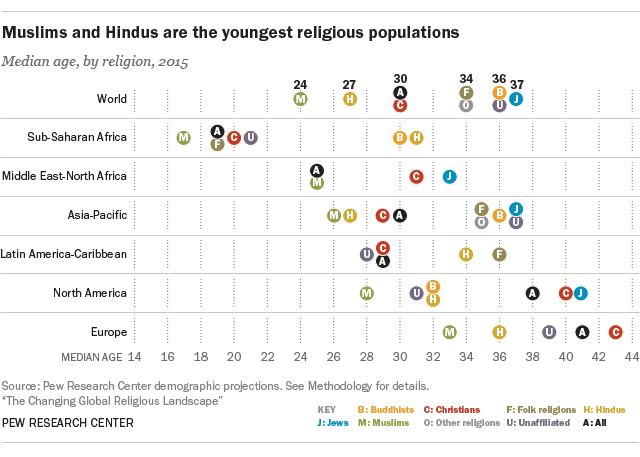

The current age distribution of each religious group is an important determinant of demographic growth. Some groups’ adherents are predominantly young, with their prime childbearing years still ahead, while members of other groups are older and largely past their childbearing years. The median ages of Muslims (24 years) and Hindus (27) are younger than the median age of the world’s overall population (30), while the median age of Christians (30) matches the global median. All the other groups are older than the global median, which is part of the reason why they are expected to fall behind the pace of global population growth.8

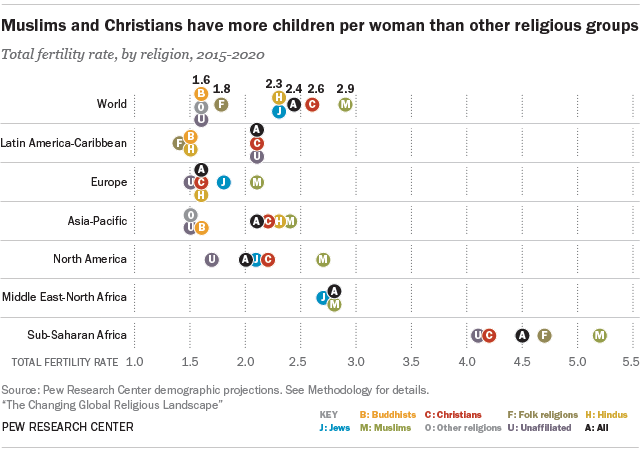

Moreover, Muslims have the highest fertility rate of any religious group – an average of 2.9 children per woman, well above replacement level (2.1), the minimum typically needed to maintain a stable population.9 Christians are second, at 2.6 children per woman. Hindu and Jewish fertility (2.3 each) are both just below the global average of 2.4 children per woman. All other groups have fertility levels too low to sustain their populations.

In addition to fertility rates and age distributions, religious switching is likely to play a role in the changing sizes of religious groups.

Pew Research Center projections attempt to incorporate patterns of religious switching in 70 countries where surveys provide information on the number of people who say they no longer belong to the religious group in which they were raised.10 In the projection model, all directions of switching are possible, and they may partially offset one another. In the United States, for example, surveys find that although it is particularly common for people who grew up as Christians to become unaffiliated, some people who were raised with no religious affiliation also have switched to become Christians.11 These types of patterns are projected to continue as future generations come of age. (For more details on how and where switching was modeled, see Appendix B: Methodology.)

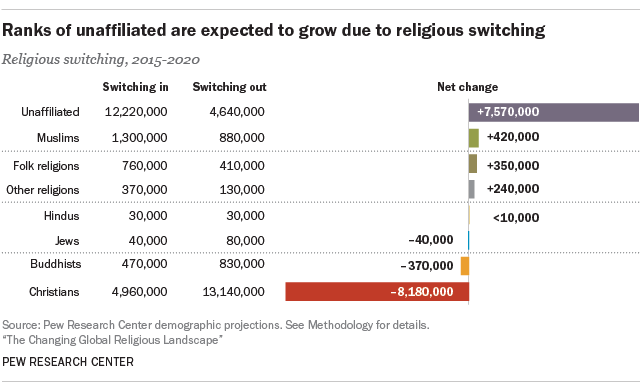

Between 2015 and 2020, Christians are projected to experience the largest losses due to switching. Globally, about 5 million people are expected to become Christians in this five-year period, while 13 million are expected to leave Christianity, with most of these departures joining the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated.

The unaffiliated are projected to add 12 million and lose 4.6 million via switching, for a net gain of 7.6 million between 2015 and 2020. The projected net changes due to switching for other religious groups are smaller.

The demographic challenges of the religiously unaffiliated

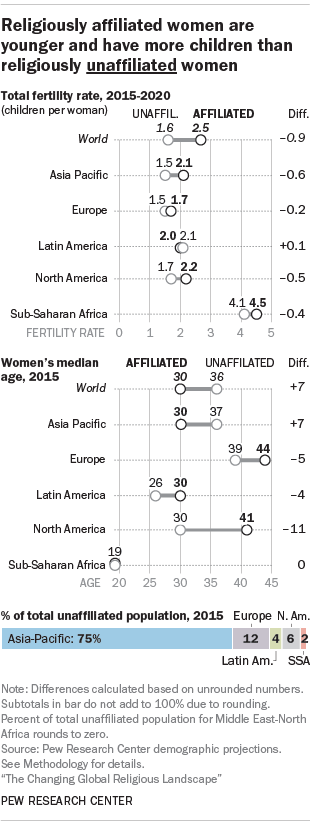

Although current patterns of religious switching favor the growth of the religiously unaffiliated population – particularly in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand – religious “nones” are projected to decline as a share of the world’s population in the coming decades due to a combination of low fertility and an older age profile.

Between 2015 and 2020, religious “nones” are projected to experience a net gain of 7.6 million people due to religious switching; people who grew up as Christians are expected to make up the overwhelming majority of those who switch into the unaffiliated group.12 Still, if current religious switching patterns continue, gains made through religious disaffiliation will not be large enough to make up for population losses due to other demographic factors.

For example, the 2015 to 2020 total fertility rate for religiously unaffiliated women is projected to be 1.6 children per woman, nearly a full child less than the rate of 2.5 children per woman for religiously affiliated women. And although religious “nones” tend to be younger than religiously affiliated people in the United States, the opposite is true at the global level: Unaffiliated women are older than the affiliated and thus more likely to be past their prime childbearing years. In 2015, the global median age for the female unaffiliated population was 36, compared with 30 for the religiously affiliated.

These demographic patterns are heavily influenced by the situation in Asia, and particularly China, which was home to 61% of the world’s unaffiliated population in 2015.

What Americans believe and expect about the global size of religious groups

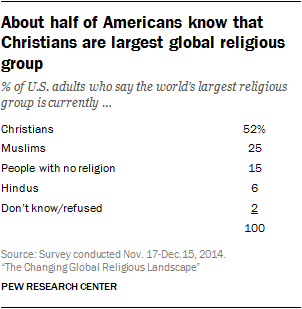

Before releasing projections of the future size of religious groups in 2015, Pew Research Center asked members of the American Trends Panel a few questions about their perceptions of the global religious landscape – and their expectations for its future.

About half of Americans (52%) have an accurate idea of which religious group is currently the largest in the world, correctly saying that Christians make up the largest religious group, while a quarter think (incorrectly) that Muslims are largest. Fewer U.S. adults say that people with no religion (15%) or Hindus (6%) are the largest religious group.

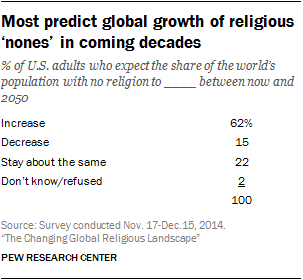

The survey also asked Americans how they expect the share of the global population with no religion to change in the coming decades. Most Americans (62%) predict that the global share of religious “nones” will increase between now and 2050 – an expectation perhaps colored by what is happening on a national level.

Indeed, in the U.S. and many other Western nations, the unaffiliated share of the population has been increasing and is expected to continue to rise as many Christians and others shed their religious identity and as younger, less religious generations replace older, more religious ones. However, because most religious “nones” live in Asia, where the religiously unaffiliated population is relatively old and has relatively low fertility, Pew Research Center projects that the global unaffiliated population will decline in the decades ahead, even after factoring in expected gains via religious switching. Only 15% of U.S. adults surveyed expect that people with no religion will decline as a share of the global population by 2050.13

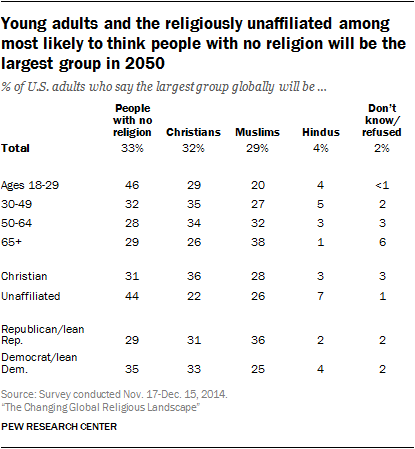

Asked which group they expect to have the most adherents globally in 2050, Americans are closely divided among those who say religious “nones” (33%), Christians (32%) and Muslims (29%). A small share (4%) anticipates that Hindus will be the largest group.

Expectations about which group will become the largest vary by respondents’ age, religion and political party affiliation. For instance, nearly half (46%) of U.S. adults under 30 predict that people with no religion will outnumber Christians, Muslims and Hindus in 2050, while only about three-in-ten of those ages 50 and older anticipate that religious “nones” will be the largest group at mid-century. Meanwhile, older Americans are more likely than young adults (under 30) to say that Muslims will be the largest group.

Christians are more likely than religious “nones” to say that Christians will be the largest group in 2050 (36% vs. 22%). And the unaffiliated are more likely than Christians to say people with no religion will be the largest group at mid-century: 44% of religious “nones” say this will be the case, compared with 31% of Christians.

Differences in expectations about the future size of religious groups also are apparent across the political spectrum. Americans who identify with or lean toward the Republican Party are more likely than those who identify as or lean Democratic to predict that Muslims will make up the largest religious group in the world in 2050 (36% vs. 25%). By contrast, Democrats are more likely than Republicans (35% vs. 29%) to expect that people with no religion will be the largest group.

How births and deaths are changing religious populations

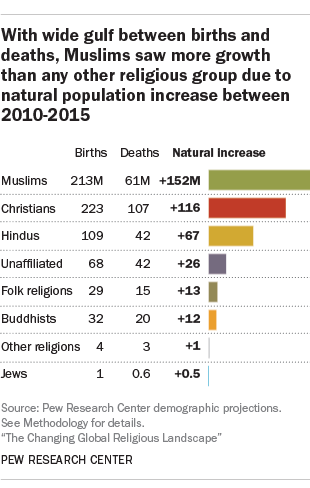

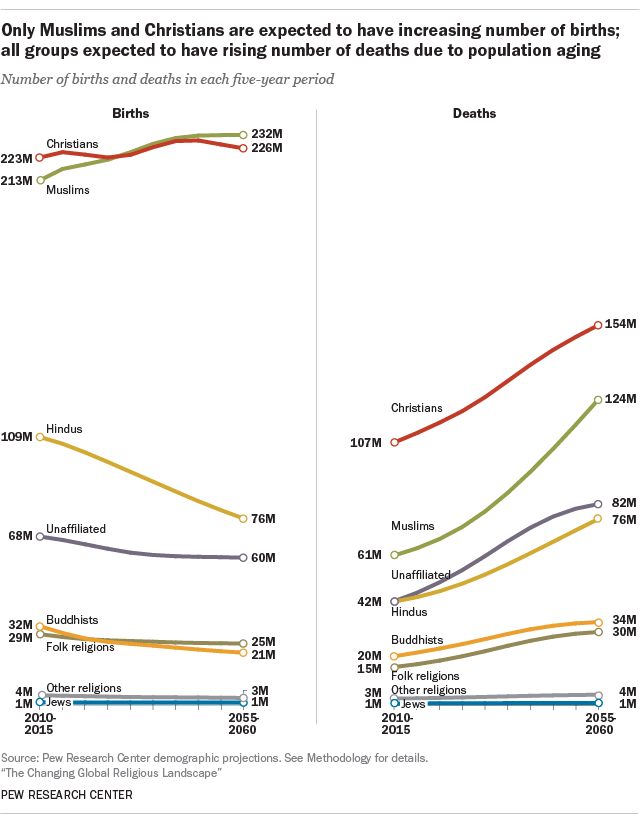

As the world’s largest religious group, Christians had the most births and deaths of any group between 2010 and 2015. During this five-year period, an estimated 223 million babies were born to Christian mothers and roughly 107 million Christians died, meaning that the natural increase in the Christian population – i.e., the number of births minus the number of deaths – was 116 million over this period.

Muslims had the second-largest number of births between 2010 and 2015, with 213 million babies born to Muslim mothers. But Muslims saw the largest natural increase of any religious group – more than 152 million people – due to the relatively small number of Muslim deaths (61 million). This large natural increase results from both high Muslim fertility and the concentration of the Muslim population in younger age groups, which have lower mortality rates.

Compared with the overall size of the religiously unaffiliated population (16% of the world’s people), there were relatively few recent births to unaffiliated mothers (10% of all births between 2010 and 2015). Religious “nones” are the third-largest group overall, and yet due to lower levels of fertility, they rank fourth behind Hindus in terms of babies born. Between 2010 and 2015, an estimated 68 million babies were born to unaffiliated mothers, compared with 109 million to Hindu mothers. Hindus also saw a much larger natural increase than the religiously unaffiliated (67 million vs. 26 million).

Births also outnumbered deaths among other major religious groups between 2010 and 2015, including among Buddhists, Jews and members of folk or traditional religions.

Beyond 2015, Christian and Muslim mothers are expected to give birth to increasing numbers of babies through 2060. But Muslim births are projected to rise at a faster rate – so much so that by 2035 the number of babies born to Muslim mothers will narrowly surpass the number born to Christian mothers. Between 2055 and 2060, the birth gap between the two groups is expected to approach 6 million (232 million births among Muslims vs. 226 million births among Christians).

By contrast, the total number of births is projected to decline steadily between 2015 and 2060 for all other major religious groups. The drop-off in births will be especially dramatic for Hindus – who are expected to see 33 million fewer births between 2055 and 2060 than between 2010 and 2015 – due in large part to declining fertility in India, which is home to 94% of the global Hindu population as of 2015.

The number of deaths is projected to increase for all religious groups between 2015 and 2060, as the world’s population continues to grow – and grow older. 14

Regional and country-level patterns of births and deaths

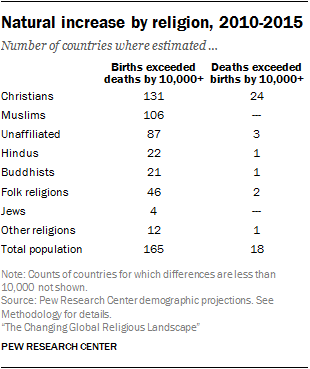

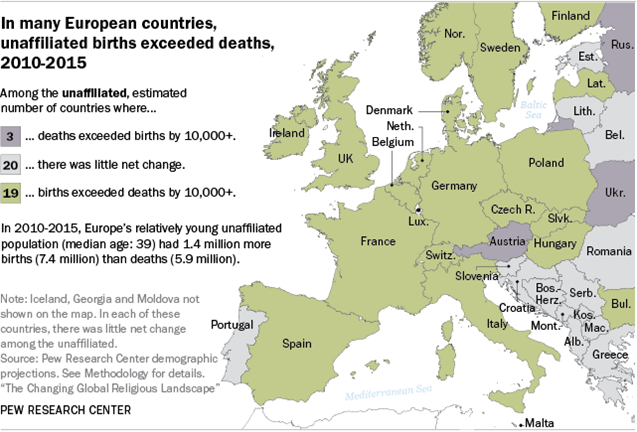

For religious groups in most countries, there is currently either positive natural increase (more births than deaths) or little net change due to births and deaths. But many European countries are experiencing a natural decrease (more deaths than births) in the populations of certain religious groups, especially Christians.

Throughout Eastern Europe and parts of Western Europe, deaths outnumbered births among Christians between 2010 and 2015 in 24 of 42 countries. Deaths also outnumbered births by at least 10,000 among religiously unaffiliated populations in Austria, Ukraine and Russia. But religious “nones” in most European countries saw either a positive natural increase (in 19 countries) or little net change during the period from 2010 to 2015 (in 20 countries). This reflects the relatively young age profile of the religiously unaffiliated compared with the Christian population in Europe.

Among Muslims, there were no European countries where the number of deaths exceeded the number of births. Throughout most of the region, the number of babies born to Muslim women exceeded the number of Muslim deaths between 2010 and 2015 (in 21 countries). In Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia and France, there were at least 250,000 more Muslim births than deaths in each country over that period. At the same time, migration is also driving Muslim population growth in Europe.

No Christian, Muslim or unaffiliated populations living in countries outside of Europe experienced more deaths than births in the 2010 to 2015 period. Similarly, other religious groups saw either positive natural increase or little net change, with a few exceptions: Buddhists in Japan, Hindus in South Africa and adherents of folk religions in South Korea and Tanzania had a larger number of deaths than births between 2010 and 2015.

There are important regional differences in birth and death trends for some religious groups. Among Christians, for example, sub-Saharan Africa experienced the biggest natural increase between 2010 and 2015 – with 64 million more births than deaths – followed by smaller Christian increases in Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia and the Pacific and North America.

In Europe, however, Christian deaths already outnumber births – a deficit that is projected to grow through 2060. And in North America, the number of Christian deaths will begin to exceed the number of births by around 2050.

These trends signal that much of Christianity’s future growth is likely to be in the global South, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa – the only region where natural increases in the Christian population are expected to grow even larger in the coming decades. (This means that not only will there continue to be more Christian births than deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, but births will exceed deaths by even larger numbers in upcoming five-year periods.) In Latin America and the Asia-Pacific region, the number of Christian births will continue to exceed the number of deaths through 2060, but the natural increases in the 2055 to 2060 time period will be much smaller than they are now as these regions experience significant declines in fertility.

The global Muslim population also is projected to undergo an important geographic shift toward sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, more Muslims live in Asia and the Pacific than in any other region, and as a result, this region had the largest natural increase in the Muslim population between 2010 and 2015.

But sub-Saharan Africa’s Muslims also experienced far more births than deaths during this period, and the natural increases in the Muslim population in sub-Saharan Africa are projected to grow even larger in the five-year periods ahead, driven by high fertility. By about 2040, the natural increase in the Muslim population in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to exceed the natural increase in Asia.

Muslims in Asia and the Middle East-North Africa region will experience slower growth in the coming decades as Muslim fertility in these regions declines. These populations will continue to have more births than deaths through 2060, but they will grow at a slower rate.

Muslims in Europe and North America also are expected to have more births than deaths through 2060.

Currently, there are more births than deaths among religious “nones” in all regions, led by the Asia-Pacific region, which is home to a majority of the global religiously unaffiliated population.

But this will change in the coming years. For people with no religion in Asia, the number of deaths will begin to exceed the number of births to unaffiliated mothers by 2030, a change driven by low fertility and a relatively old unaffiliated population in China. By 2035, unaffiliated deaths are expected to outnumber births in Europe as well.