Question 1: Measuring religious identity

How does Pew Research Center measure the religious identity of survey respondents and the religious composition of the U.S.?

Answer: Generally, we rely on respondents’ self-identification. A key question we ask in many surveys is: “What is your present religion, if any? Are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox such as Greek or Russian Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular?”

Those who answer this question by describing themselves as “Protestant” are categorized as Protestants. Some respondents (roughly one-in-ten or more, on average, in recent surveys) answer the question by volunteering that they are “Christian” or “just Christian,” and they, too, are categorized as Protestants. Respondents who say they belong to nondenominational Christian churches also go into the broad Protestant category.

Those who describe themselves as “Catholic” or “Roman Catholic” are categorized as Catholics. And the large – and growing – number of survey respondents who describe themselves as “atheist,” “agnostic” or “nothing in particular” are often combined into an umbrella group called the religiously unaffiliated (sometimes also called the religious “nones”).

Similarly, those who describe themselves as “Mormon,” “Orthodox,” “Jewish,” “Muslim,” “Buddhist” or “Hindu” are categorized as such in Pew Research Center reporting. Many Pew Research Center surveys encounter too few respondents from these smaller religious groups to permit analysis of their views and characteristics.1 However, the Center’s larger surveys (like the 35,000 person U.S. Religious Landscape Study) do make it possible to report on the characteristics of these groups. In addition, the Center has conducted several surveys designed specifically to capture the views of smaller religious groups in the U.S., including three surveys of U.S. Muslims, a 2013 survey of U.S. Jews, a 2012 survey of Asian Americans (including large samples of Buddhists and Hindus), and a 2011 survey of U.S. Mormons.

Respondents who answer by describing their religion as “something else” are asked to specify further. Many of them provide answers suggesting they belong in one of the existing categories, and they are categorized accordingly. For example, after first saying “something else,” many respondents specify that they are Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, etc., and are subsequently categorized as Protestants.

Others say they are “LDS” (an abbreviation for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and are coded as Mormons, while still others give a variety of answers (e.g., “Sunni” or “Sufi”) that indicate they are Muslims. The few remaining respondents (typically 1% or 2% of all respondents) who specify something that does not belong in any of the existing categories (including members of smaller religious groups like Sikhs, Baha’is and Rastafarians, as well as those who say they are “spiritual but not religious” or that they have their “own beliefs”) remain categorized as “something else.”

We sometimes use a more expansive definition, which includes not just people who identify religiously with a group, but also those who self-identify culturally or ethnically. For example, the Center’s 2013 survey of U.S. Jews included both respondents who described themselves as Jewish when asked about their religion as well as those who described themselves (religiously) as “atheist,” “agnostic,” or “nothing in particular” if they also currently considered themselves Jewish or partially Jewish “aside from religion,” and they were raised Jewish or had a Jewish parent. Similarly, our 2015 survey of U.S. Catholics and Family Life included analysis of “cultural Catholics” in addition to those who identified as Catholic by religion. Instances of this kind of more expansive approach to defining groups are rare, however, and are clearly noted in our reports.

Question 2: Religious identity vs. religious belief

But what about Catholics who don’t attend church? Can someone really be Catholic if they don’t attend Mass regularly? Similarly, what about Mormons who don’t believe in God? Can someone who doesn’t believe in God be Mormon?

Answer: In our surveys, members of religious groups are categorized based on their self-identification with the group, not on the basis of their religious beliefs or practices. We do ask about beliefs and practices, but those are separate questions. This allows us to see, for example, that among self-described Catholics, roughly four-in-ten say they attend religious services at least once a week, while a similar share say they attend Mass once or twice a month or a few times a year, and one-in-five say they seldom or never attend Mass. All are categorized as Catholics in the Center’s reports, though in many of our larger surveys, we are able to break down the Catholic category into subgroups and compare Catholics who say they go to Mass weekly with those who attend less often.

Defining religious categories on the basis of self-identification has a number of benefits, chief among them that this kind of approach makes it possible to describe the diversity of belief and practice that exists within every religious tradition in the U.S. Some religious traditions are composed of people who overwhelmingly profess to believe in the unique teachings of their faith. For example, the Center’s 2011 survey of U.S. Mormons found that 94% of self-described Mormons believe that the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a prophet of God, and 91% believe that the Book of Mormon was written by ancient prophets and translated by Joseph Smith. The same survey found that 82% of Mormons say religion is very important in their lives, and 77% say they attend religious services on at least a weekly basis.

Other religious groups exhibit lower levels of uniformity. For example, Americans who identify as Jewish when asked about their religion are roughly evenly divided between those who say religion is very important in their lives (31%), those who say it is somewhat important in their lives (35%), and those who say religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives (33%).

Pew Research Center surveys even find that a few self-described atheists say they believe in God or a universal spirit. There are a number of possible explanations for this paradox. Some respondents may identify as atheists because they reject traditional images of God, even though they believe there is some spiritual force in the universe. Others may identify as atheist primarily as a means of registering an objection to organized religion. And a few self-described atheists are unclear on what, exactly, the word “atheist” means. Whatever the explanation, the larger point is that no religious group in the U.S. is a monolith. There is diversity of belief and practice within every religious tradition, and defining religious traditions on the basis of self-identification makes it possible to illustrate the multiplicity of belief and practice inside each group.

In short, we do not seek to make any judgments about what characteristics may or may not disqualify someone from a particular group. This can often be a matter of opinion; for example, most U.S. Jews say a person cannot be Jewish if he or she believes Jesus was the messiah, but a substantial minority disagree. As a neutral research organization, Pew Research Center does not take positions on these sorts of debates.

Question 3: Subgroups of Protestants

Protestants are the single largest religious group in the United States. But Pew Research Center usually disaggregates them into several subgroups (for example, evangelical Protestants, mainline Protestants, black Protestants). How do you do this?

Answer: To categorize Protestants into subgroups, we typically choose between two different methods, depending on the survey. In most of our surveys, we employ a self-identification approach, which relies on information about respondents’ race and whether they self-identify as a “born-again or evangelical Christian” to sort them into subgroups. In some of our largest surveys, however, we employ a denominational approach, in which Protestants are sorted into subgroups based on the specific denomination with which they identify.

The self-identification approach

In many of the Center’s surveys, including most of our political polling, respondents are asked the religious identification question described above: “What is your present religion, if any? Are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox such as Greek or Russian Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular?”

Then, in addition, all Christians (including people who identify as any type of Protestant as well as Catholics, Mormons, etc.) are asked a follow-up question: “Would you describe yourself as a born-again or evangelical Christian, or not?” Finally, all respondents receive a standard series of demographic questions, including about their race/ethnicity.

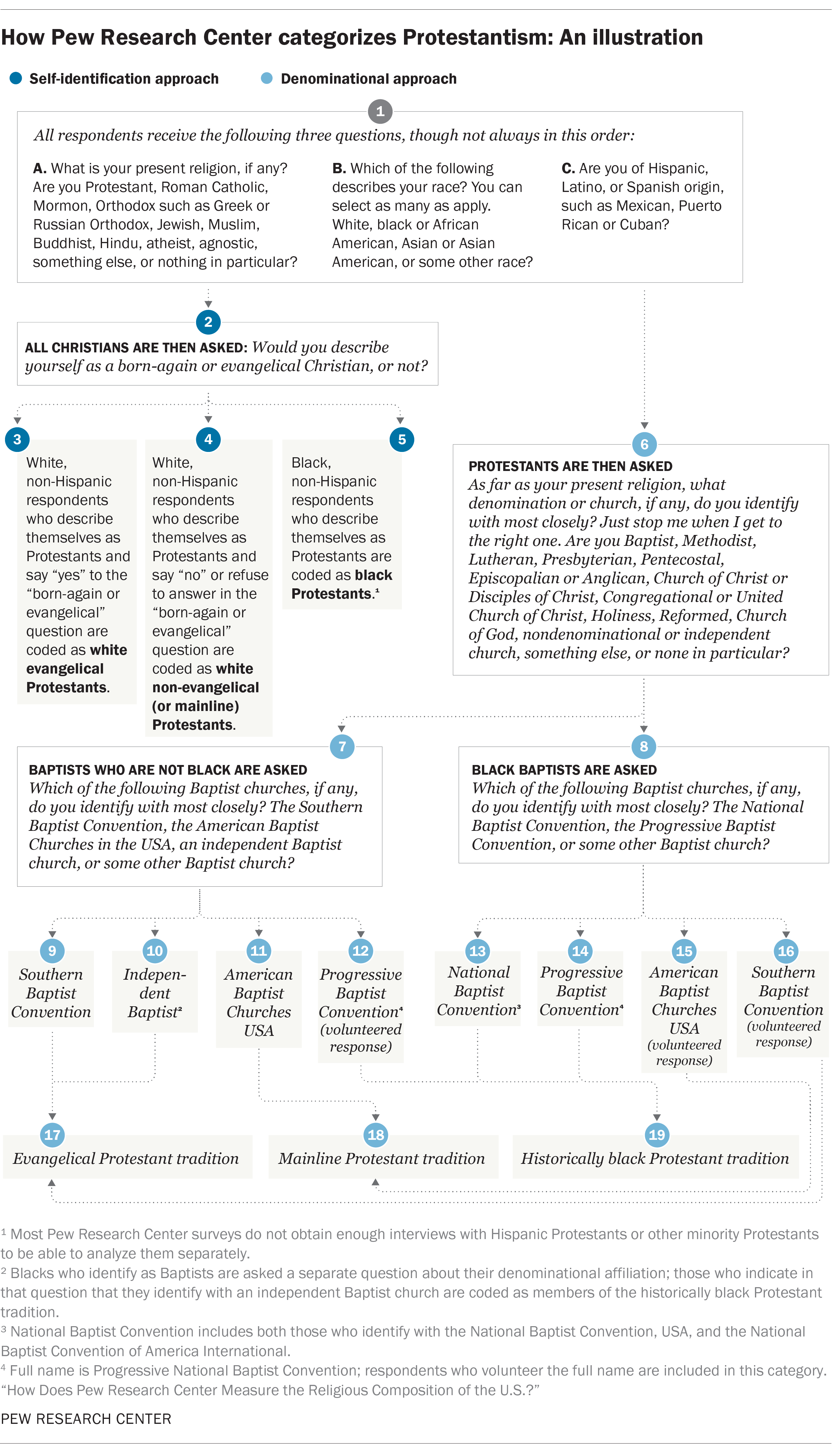

By combining the answers to all these questions, we generally divide Protestants into three groups.

- White evangelical Protestants are defined as those who answer the first question by identifying as Protestant (or by volunteering that they are “Christian” or “just Christian”), who answer the second question by saying they consider themselves to be “born-again or evangelical” Christians, and who describe themselves as white and non-Hispanic when asked about their race and ethnicity.

- White non-evangelical (or mainline) Protestants are defined as those who answer the first question by identifying as Protestant (or by volunteering that they are “Christian” or “just Christian”), who answer the second question by saying they would not describe themselves as “born-again or evangelical” Christians (or who decline to answer the question), and who furthermore describe themselves as white and non-Hispanic when asked about their race and ethnicity.

- Black Protestants are defined as those who answer the first question by identifying as Protestant (or by volunteering that they are “Christian” or “just Christian”), and who describe themselves as black and non-Hispanic when asked about their race and ethnicity. The “black Protestant” category, when defined this way, includes both those who describe themselves as “born-again or evangelical” Christians, and those who do not.

Most Pew Research Center surveys do not obtain enough interviews with Hispanic Protestants or other minority Protestants to be able to analyze them separately.

The denominational approach

While the self-identification approach outlined above is the way the Center typically analyzes subgroups of Protestants, it is not the only approach used in the Center’s analyses. Specifically, in the Center’s two large Religious Landscape Studies, first conducted in 2007 and then again in 2014, Protestants are categorized into one of three major traditions (evangelicalism, mainline Protestantism, or the historically black Protestant tradition) using a denominational approach.2

The denominational approach employed in the Landscape Studies requires asking a longer series of detailed questions about religious affiliation than can be carried on a typical survey. The first question in the series is identical to the one described above: “What is your present religion, if any? Are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox such as Greek or Russian Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular?”

Second, Protestants (and those who volunteer that they are “Christian” or “just Christian”) are asked about what denominational family they identify with. Specifically, Protestants are asked, “As far as your present religion, what denomination or church, if any, do you identify with most closely? Just stop me when I get to the right one. Are you Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Episcopalian or Anglican, Church of Christ or Disciples of Christ, Congregational or United Church of Christ, Holiness, Reformed, Church of God, nondenominational or independent church, something else, or none in particular?”

Finally, Protestants receive a third question based on their answer to the second question – and sometimes based also on their race. Baptists who are not black, for example, are asked, “Which of the following Baptist churches, if any, do you identify with most closely? The Southern Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A., an independent Baptist church, or some other Baptist church?” Baptists who are black are asked, “Which of the following Baptist churches, if any, do you identify with most closely? The National Baptist Convention, the Progressive Baptist Convention, or some other Baptist church?” Presbyterians of all races are asked: “Which of the following Presbyterian churches, if any, do you identify with most closely? The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), Presbyterian Church in America, or some other Presbyterian church?” And those identifying with other denominational families are asked a similar question tailored specifically to them. (For the full list of the questions asked and their exact question wording, see the Landscape Study questionnaire.)

The information gleaned from this series of questions is used to categorize Protestants as members of the evangelical, mainline, or historically black Protestant tradition based as much as possible on their specific denominational affiliation, and not on their answers to the born-again/evangelical self-identification question (to the extent it can be avoided).3 When this denominational measurement strategy is employed, evangelicals and mainline Protestants can include nonwhites, and the historically black Protestant tradition can include nonblacks. For example, all people who self-identify with the Southern Baptist Convention are classified as evangelicals (even if they are not white and even if they do not self-identify as born-again or evangelical Christians). All people who identify with the American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A. are categorized as mainline Protestants (even if they do identify as “born-again or evangelical Christians”).4And all people who self-identify with the National Baptist Convention are categorized in the historically black Protestant tradition (even if they are not black).5 Complete details about the denominational approach to categorizing Protestants are available in an appendix to the Religious Landscape Study reports.

Despite the detailed religious affiliation questions in the Religious Landscape Studies, many respondents (more than a third of all Protestants in the 2014 study) are either unable or unwilling to describe their specific denominational affiliation.6 For instance, some respondents describe themselves as “just a Lutheran” or “just a Presbyterian” or “just a Methodist.” In these cases, respondents are sorted into one of the three Protestant traditions (evangelical, mainline, or historically black Protestant tradition) in two ways:

- First, black respondents who give vague denominational affiliations (e.g., “just a Methodist”) but who say they belong to a Protestant family with a sizable number of historically black churches (including the Baptist, Methodist, nondenominational, Pentecostal and Holiness families) are coded as members of the historically black Protestant tradition. Black respondents in denominational families without a sizable number of churches in the historically black Protestant tradition (e.g., the Lutheran and Presbyterian denominational families) are coded as members of the evangelical or mainline Protestant tradition based on their response to the question asking whether they identify as a born-again or evangelical Christian.

- Second, nonblack respondents who give vague denominational affiliations and who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Christians are coded as members of the evangelical tradition; otherwise, they are coded as members of the mainline tradition.

Overall, 38% of Protestants in the 2014 Landscape Study offered a vague denominational identity and were classified, in part, on the basis of their race and/or their answer to the question about whether they identify as a born-again or evangelical Christian.

For a discussion of how Protestant groups compare to each other depending on which measurement strategy (the self-identification approach or denominational approach) is employed, see Question 7 below.

Question 4: Race and religion

Aren’t most black Protestants evangelicals? And if so, then why do you analyze them separately in so many reports?

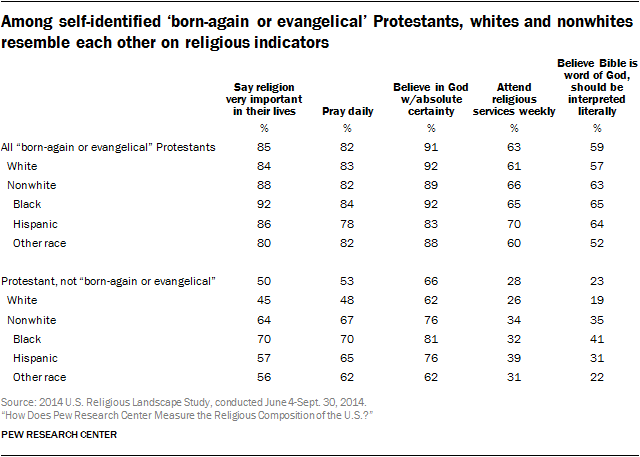

Answer: Most nonwhite Protestants (70%), including 71% of African American Protestants, say “yes” when asked directly whether they consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians. And in terms of their religious beliefs and practices, there are, indeed, a number of important ways in which white evangelicals and evangelical minorities closely resemble each other. For example, 84% of white born-again or evangelical Protestants say religion is very important in their lives, and 88% of nonwhite evangelicals say the same, including 92% of black evangelical Protestants who say this. And more than eight-in-ten white evangelicals say they pray every day (83%), as do 82% of nonwhite evangelicals (including 84% of black self-identified evangelicals).

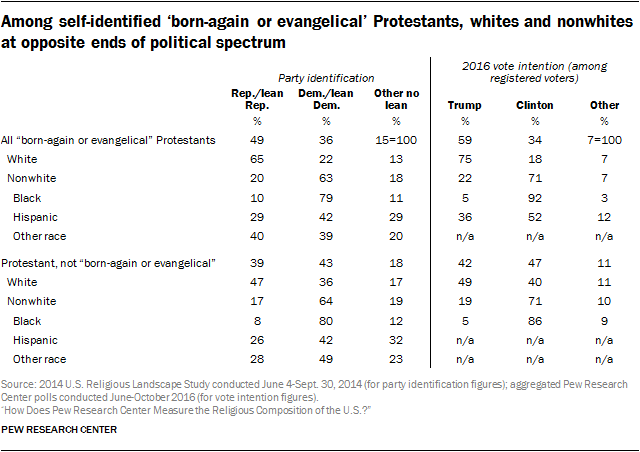

But while white and nonwhite evangelicals (including black evangelicals) share many religious characteristics in common, they are sharply divided when it comes to politics, and their views about many key social and cultural issues. White evangelicals, simply put, are among the most strongly Republican, conservative constituencies in American politics. By contrast, nonwhite evangelicals (especially black evangelicals) are among the most strongly and consistently Democratic groups in the U.S. electorate. Pew Research Center regularly focuses on public opinion on political and cultural topics, and this is why white evangelicals and black Protestants often are examined separately in our reports.

When asked directly about their partisan leanings, nearly two-thirds of white evangelical Protestants say they lean toward or identify with the Republican Party, while just 22% lean toward or identify with the Democratic Party (the remaining 13% identify as political independents or with another party and decline to lean toward either the GOP or the Democratic Party). Among nonwhite evangelicals, these figures are reversed; 63% identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, while just 20% prefer the GOP. The Democratic advantage is especially lopsided among black evangelical Protestants, among whom eight-in-ten (79%) say they identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, compared with just 10% who prefer the GOP. On this measure, there is no discernible difference between black evangelical Protestants and black non-evangelical Protestants, among whom 80% favor the Democratic Party and just 8% identify with or lean toward the GOP.7 In other words, with respect to partisanship, black evangelicals are much more in line with black non-evangelical Protestants than with white evangelicals.8

The same pattern is evident in voting behavior.9 In pre-election polling conducted during the 2016 presidential election, three-quarters of white evangelical Protestants indicated that they intended to vote for Republican Donald Trump (75%), compared with just 18% who intended to cast a ballot for Democrat Hillary Clinton. Among nonwhite evangelicals, these figures were reversed, with 71% expressing support for Clinton and just 22% saying they backed Trump. Among black evangelical Protestants, support for Clinton swelled to 92%, compared with just 5% who intended to vote for Trump.

Whites also express much more affinity for the GOP than do nonwhites among non-evangelical Protestants, though they (white non-evangelical Protestants) are significantly less Republican than are white evangelicals. Nearly half of white non-evangelical Protestants identify with or lean toward the GOP, which is nearly three times the share of nonwhite, non-evangelical Protestants who say the same. And whereas 49% of white non-evangelical Protestants expressed an intention to vote for Trump in the 2016 election, just 19% of nonwhite, non-evangelical Protestants indicated they intended to vote for Trump.

In short, there is no escaping the importance and explanatory power of race when it comes to partisanship and electoral politics. Analyses that explore the link between religion and partisanship or voting without taking race into account would obscure far more than they would illuminate.

Question 5: Religion and politics

Doesn’t the strong support that Donald Trump received from white evangelicals suggest that the term “evangelical” is now a political label as much as a religious one? And isn’t it true that among whites, there are lots of self-described evangelicals who actually aren’t very religious, but who call themselves evangelicals just because they’re politically conservative or Republican?

Answer: During the 2016 presidential campaign, some commentators expressed surprise at the high level of support Donald Trump received from white evangelical voters, and suggested that Trump’s rise may have been driven in large part by outsized support from evangelicals who are not particularly religious.

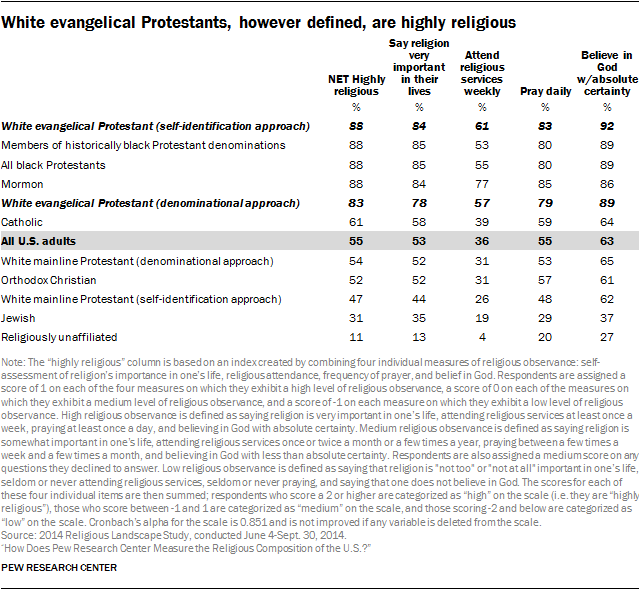

But the notion that there are large numbers of white evangelicals (however defined) who are not particularly religious is false. Whether evangelicalism is defined by the denominational or the self-identification approach, white evangelicals are among the most religiously observant groups in the population. (For details on the difference between the denominational and the self-identification approach to subdividing Protestants, see Question 3 above.)

Under the self-identification approach, 88% of white evangelical Protestants interviewed as part of the 2014 Religious Landscape Study score “high” on an index of religiosity that incorporates indicators of religious attendance, frequency of prayer, belief in God, and a self-assessment of religion’s importance in one’s life. While some other religious groups (including Mormons and black Protestants) exhibit similar levels of religiosity, there is no group that exhibits a significantly higher level of religious commitment, and many religious groups exhibit much lower levels of religiosity.10 Under the denominational approach, 83% of white evangelicals score high on the same scale.

Question 6: Religious trends

Have fewer people identified as evangelicals in recent years, in part because of the political connotations of the label? More specifically, are people who dislike President Trump abandoning the “evangelical” label for themselves because of evangelicals’ strong support for Trump?

Answer: This is a difficult question to answer directly, in part because a definitive answer would require longitudinal data (that is, the same respondents would be interviewed on multiple occasions so researchers could see how their answers change over time). For the time being, the best we can do is to consider this question in the context of longer-term trends in American religion.

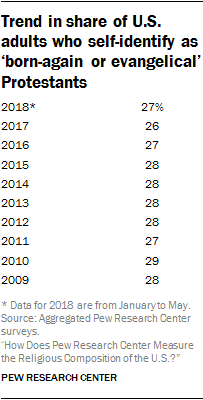

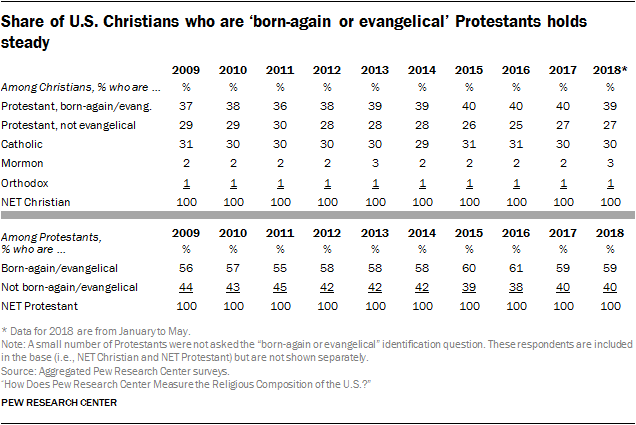

Our data show, on the one hand, that the share of Americans who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants has been fairly stable in recent years. In 2009 (which was the first year Pew Research Center asked its now-standard question about religious identification and conducted most of its surveys in both English and Spanish), 28% of American adults identified as born-again or evangelical Protestants, and this figure held quite stable through 2015. (Trump declared his candidacy for president on June 16, 2015.)

Between 2015 and 2017, however, there appears to have been a slight downturn in the share of Americans who identified as evangelical Protestants, which slipped to 26% in 2017. Surveys conducted thus far in 2018 suggest that the number may have recently rebounded to 27%, though it is too early, as of this writing, to know for sure.11

In short, surveys suggest that the share of self-described born-again or evangelical Protestants in the U.S. is either holding steady or declining very slightly.

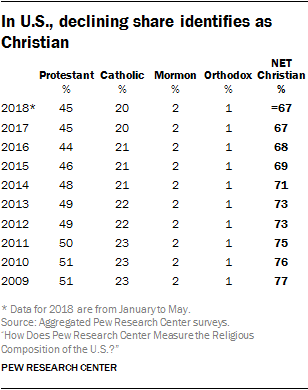

But even if there has been a slight decline in the share of Americans who identify as evangelical Protestants, it can only be understood against the backdrop of broader trends in American religion. The share of Americans who identify with Christianity writ large has been declining for some time. In 2009, more than three-quarters of U.S. adults (77%) identified with some kind of Christianity, including 51% who were Protestant, 23% who were Catholic, 2% who were Mormon and 1% who identified with Orthodox Christianity. By 2014, the share of adults identifying with Christianity had slipped to 71%. And today, 67% of Americans describe themselves as Christians, including 45% who are Protestant, 20% who are Catholic, 2% who are Mormon and 1% who identify with Orthodox Christianity.

In other words, to the extent that there has been a decline in the share of Americans who identify as evangelicals, this is part of a broader shift away from Christianity altogether, and these trends long predate the emergence of Trump as a political force.

Also, while the share of U.S. adults who identify with Christianity (including Protestantism) has been declining, among those who are Christian, the percentage who identify with the “born-again or evangelical” Protestant label is at least as high today (39%) as in 2009 (37%) or in the years immediately prior to Trump’s presidential bid (39% in both 2013 and 2014). This suggests that any decline in the share of born-again or evangelical Protestants in the U.S. population is attributable mainly to the decline in the share of Americans who identify with Christianity, and not to a decline in the share of Christians who identify with the “born-again or evangelical” Protestant label.12

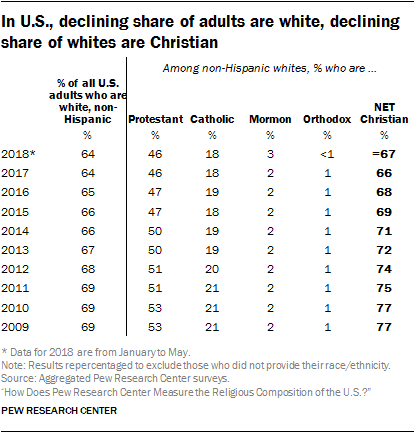

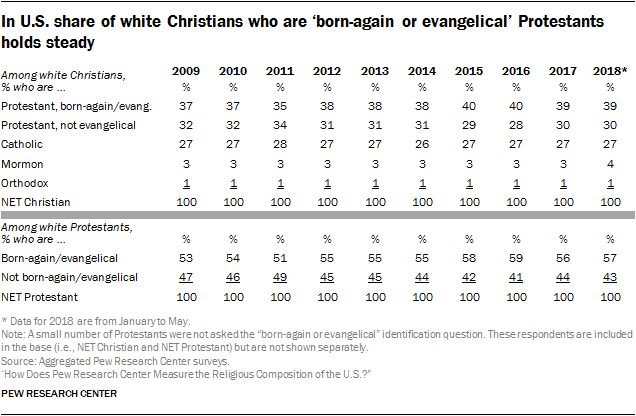

While the share of Americans who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants is holding steady or perhaps declining very slightly, there has been a more clear-cut decline in the share of U.S. adults who are white born-again or evangelical Protestants. In 2009, 20% of U.S. adults were white born-again or evangelical Protestants. Today, 17% of U.S. adults fit this description. But here again, these trends were underway long before Trump’s emergence on the political scene, and they seem to have more to do with broader trends in American religion (including declines in the share identifying with Christianity) and with broader trends in the racial and ethnic composition of the population (including a decline in the share of all U.S. adults who are white) than they do with abandonment of the “born-again or evangelical” label.

In Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 2017 and early 2018, just under two-thirds of all respondents have been white (64%). A decade ago, by contrast, roughly seven-in-ten U.S. adults were white. As the share of adults who are white declined in recent years, so too did the share of whites who describe themselves as Christians. Today, two-thirds of whites (67%) identify as Christians, down from 77% in 2009.

But while whites are declining as a share of the population, and identification with Christianity is declining among whites, the percentage of white Christians who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants is quite stable. In 2009, 37% of white Christians in the U.S. were born-again or evangelical Protestants. Today, 39% of white Christians describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants.

Among white Protestants, the share who currently identify as born-again or evangelical Christians (57%) may appear to be down slightly from its peak in late 2016 (59%). But the percentage of born-again or evangelical Christians among white Protestants is currently on par with estimates from 2014 and, if anything, slightly above readings taken in 2009 (53%) and 2011 (51%).

These data do not prove that no one has abandoned the “born-again or evangelical” label due to concerns about the association between evangelicalism and support for Trump. There may be individuals who have distanced themselves from the “born-again or evangelical” label for exactly those reasons. And, by the same token, it is also possible that there are individuals who have come to adopt the “born-again or evangelical” label because of their admiration for Trump and their sense that evangelicals strongly support him.

However, there is no evidence in Pew Research Center surveys that a sudden, mass movement away from evangelicalism began during the Trump administration or his presidential election campaign. The share of white born-again or evangelical Christians in the U.S. population has been declining, but this gradual shift seems to be part of long-term religious and demographic changes that have been underway for decades. Whether Trump’s popularity among white evangelicals has hastened (or slowed) this shift is not yet clear.

Question 7: Impact of measurement strategy for understanding Protestantism

What difference does the choice of approach for measuring Protestantism – denominational vs. self-identification – make for understanding the characteristics of Protestants?

Answer: There is substantial overlap, but not a perfect match, between the denominational and self-identification approaches to categorizing Protestants. Both methods produce similar estimates of the size of the evangelical population, and they result in similar religious and demographic portraits of the major Protestant traditions.13 (For details on the difference between the denominational and the self-identification approach to subdividing Protestants, see Question 3 above.)

To illustrate the overlap between the denominational and self-identification approaches, this analysis is restricted to whites who self-identify as Protestants, since the self-identification approach typically focuses on white born-again or evangelical Protestants and white non-evangelical Protestants, with black Protestants sorted into their own category (see Question 3 above for more details).14

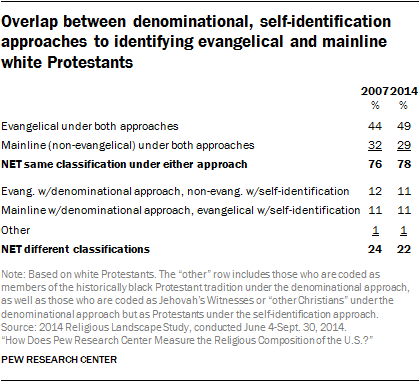

Overlap

In the 2014 Religious Landscape Study, more than three-quarters of white Protestants (78%) would have been categorized the same way under either the denominational or self-identification approach, including 49% who qualify as evangelicals under both the denominational and self-identification approaches and 29% who are categorized as non-evangelical (or mainline) Protestants under either approach. Just 22% of white Protestants would have been classified differently under the denominational and self-identification approaches. The data show, furthermore, that the correspondence between the denominational and self-identification approach is, if anything, growing closer over time. In the first Religious Landscape Study, conducted in 2007, a slightly smaller share of white Protestants (76%) would have been categorized the same way under both approaches.

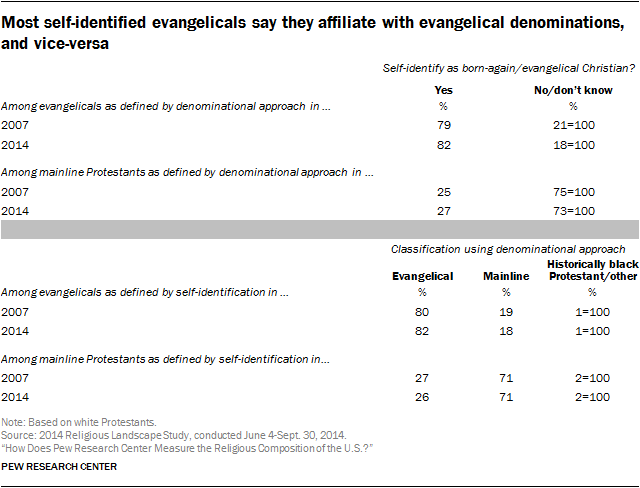

Looked at another way, the data show that fully eight-in-ten of those classified as white evangelical Protestants under the denominational approach (82%) answer the self-identification question affirmatively, saying yes when asked whether they would describe themselves as a born-again or evangelical Christian. And nearly three-quarters of those classified as mainline Protestants under the denominational approach (73%) answer the self-identification question by saying no, they do not consider themselves to be born-again or evangelical Christians.15 Similarly, the vast majority of white Protestants who self-identify as born-again or evangelical Christians are classified as evangelicals under the denominational approach (82%), and roughly seven-in-ten white Protestants who do not self-identify as born-again or evangelical Christians are categorized as mainline Protestants under the denominational approach.

The data also show that the two approaches, the denominational approach and the self-identification method, produce identical estimates of the overall size of the white evangelical and non-evangelical (or mainline) Protestant categories. Using the denominational approach, the Landscape Study estimates that 19% of all U.S. adults are white evangelical Protestants and 13% of all U.S. adults are white mainline Protestants. The self-identification approach produces identical estimates; 19% of all U.S. adults are white born-again or evangelical Protestants, and 13% are white non-evangelical Protestants.

Demographics, religious beliefs and practices, and politics

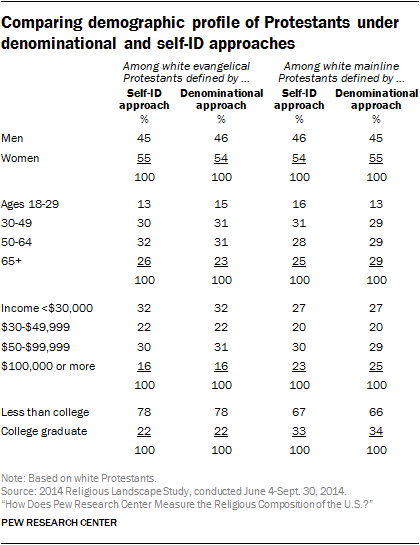

The demographic profiles of evangelical and non-evangelical Protestants are exceedingly similar under either measurement approach. For example, 54% of white evangelicals are women when the denominational strategy is employed, and 55% of white evangelicals are women when the self-identification approach is used. With respect to educational attainment, the data show that 34% of white mainline Protestants defined using the denominational approach are college graduates, as are 33% of white non-evangelical Protestants under the self-identification approach. Evangelicals as defined using the denominational method are somewhat younger than self-identified evangelicals, and mainline Protestants defined by the denominational method are somewhat older than non-evangelical Protestants categorized as such under the self-identification method. Overall, however, the two methods for classifying white Protestants produce very similar demographic profiles.

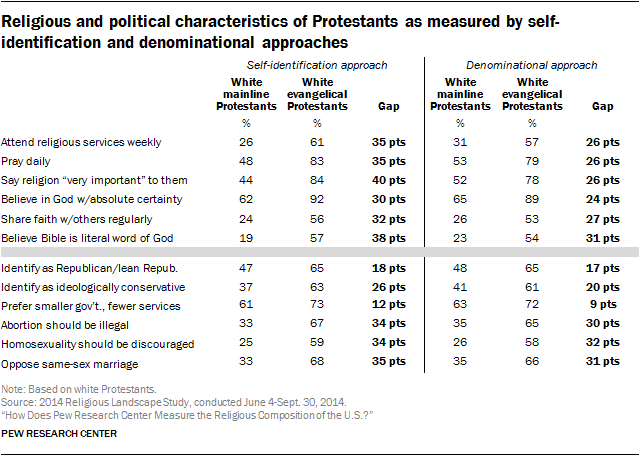

Religiously, white evangelical Protestants are much more observant than are white mainline Protestants under both the denominational and self-identification approaches to categorization. For instance, 83% of white evangelical Protestants as defined by the self-identification approach say they pray every day, as do 48% of white mainline Protestants; the gap, then, between the share of white evangelicals who pray every day and the share of white mainline Protestants who do the same is 35 points under the self-identification approach. When white Protestants are divided into evangelical and mainline categories using their denominational affiliation, the gap in daily prayer is 26 points (79% among evangelicals vs. 53% among mainline Protestants).

The data reveal a similar pattern with respect to political opinions. Evangelicals are substantially and consistently more Republican and more conservative than mainline Protestants regardless of the measurement strategy. For example, evangelicals are 18 points more likely than white mainline Protestants to say they identify with or lean toward the Republican Party under the self-identification approach, and they are 17 points more likely than mainline Protestants to say they favor the GOP when the denominational strategy is used.