Computational analysis of nearly 50,000 sermons reveals differences in length and content across major Christian traditions

Many surveys have asked Americans about their religious affiliations, beliefs and practices, including what religious group they belong to – if any – and how often they attend services at a church or other house of worship. But less is known about what churchgoing Americans hear during religious services. Frequent churchgoers may have a good sense of what kind of sermons to expect from their own clergy: how long they usually last, how much they dwell on biblical texts, whether the messages lean toward fire and brimstone or toward love and self-acceptance. But what are other Americans hearing from the pulpits in their congregations?

A new Pew Research Center analysis begins to explore this question by harnessing computational techniques to identify, collect and analyze the sermons that U.S. churches livestream or share on their websites each week. To gather the data used in this report, the Center built computational tools that identified every institution labeled as a church in the Google Places application programming interface (API), collected and transcribed all the sermons publicly posted on a representative sample of their websites during an eight-week period, and analyzed the content of the sermons in a few relatively simple ways. For practical reasons, this exploration is limited to Christian churches and does not describe sermons delivered in synagogues, mosques or other non-Christian congregations.1

How this report defines a sermon

This process produced a database containing the transcribed texts of 49,719 sermons shared online by 6,431 churches and delivered between April 7 and June 1, 2019, a period that included Easter.2 These churches are not representative of all houses of worship or even of all Christian churches in the U.S.; they make up just a small percentage of the estimated 350,000-plus religious congregations nationwide. Compared with U.S. congregations as a whole, the churches with sermons included in the dataset are more likely to be in urban areas and tend to have larger-than-average congregations (see the Methodology for full details).

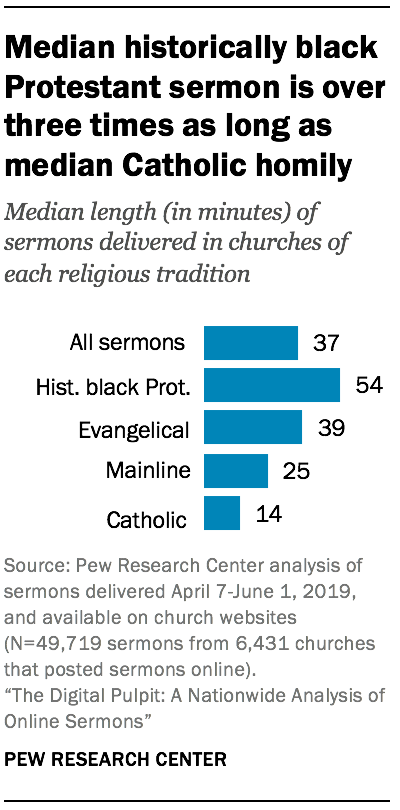

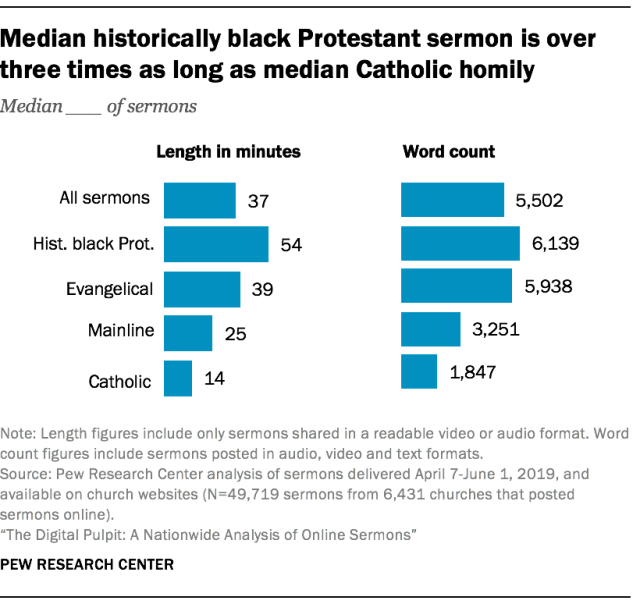

The median sermon scraped from congregational websites is 37 minutes long. But there are striking differences in the typical length of a sermon in each of the four major Christian traditions analyzed in this report: Catholic, evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant and historically black Protestant.3

Catholic sermons are the shortest, at a median of just 14 minutes, compared with 25 minutes for sermons in mainline Protestant congregations and 39 minutes in evangelical Protestant congregations. Historically black Protestant churches have the longest sermons by far: a median of 54 minutes, more than triple the length of the median Catholic homily posted online during the Easter study period.

The median is the middle number in a list of figures sorted in ascending or descending order. For instance, the median of [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] is 3. Medians are often used when describing data that contain a small number of unusually large or small values (“outliers”) that can adversely affect other statistics, such as the mean.

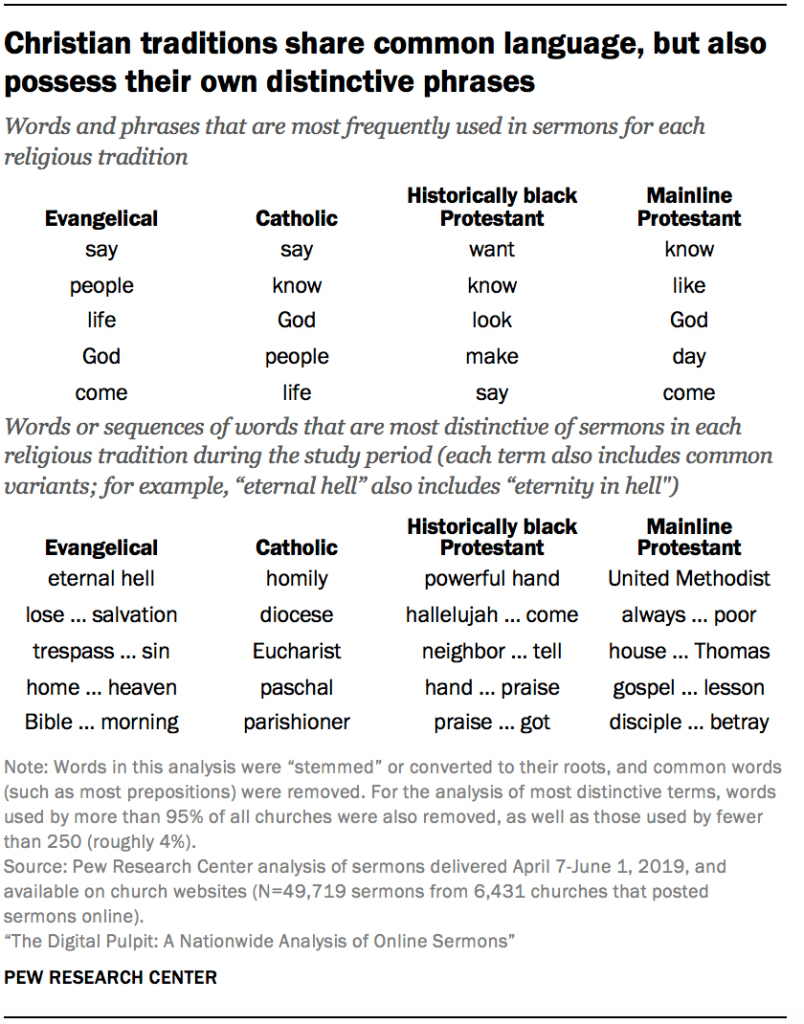

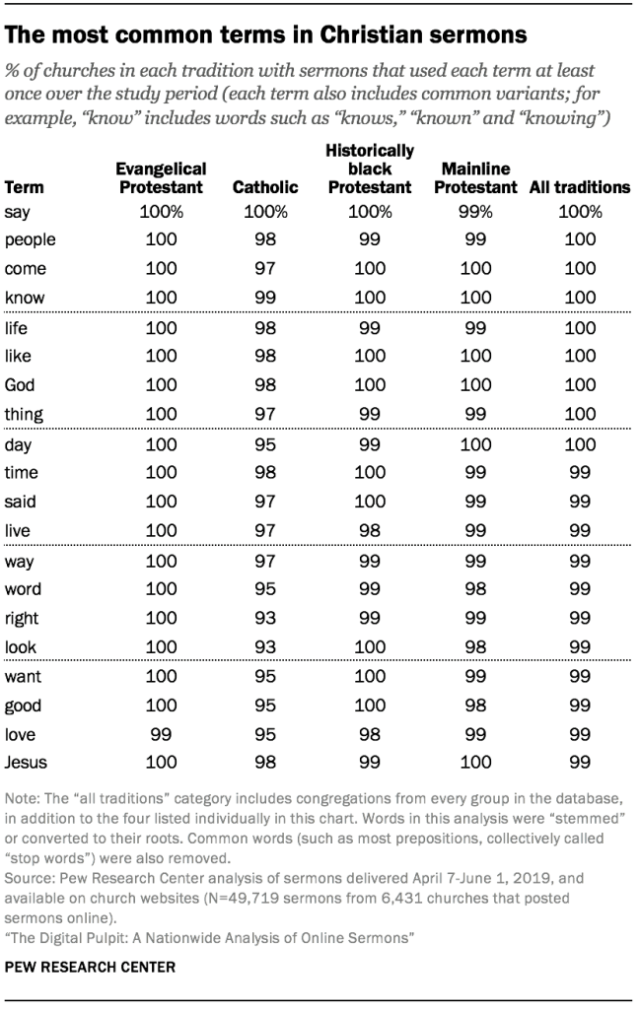

Researchers also conducted a basic exploration of sermons’ vocabulary. Several words frequently appear in sermons at many different types of churches – for instance, words such as “know,” “God” and “Jesus” were used in sermons at 98% or more of churches in all four major Christian traditions included in this analysis.4

This computational text analysis also found many words and phrases that are used more frequently in the sermons of some Christian groups than others.

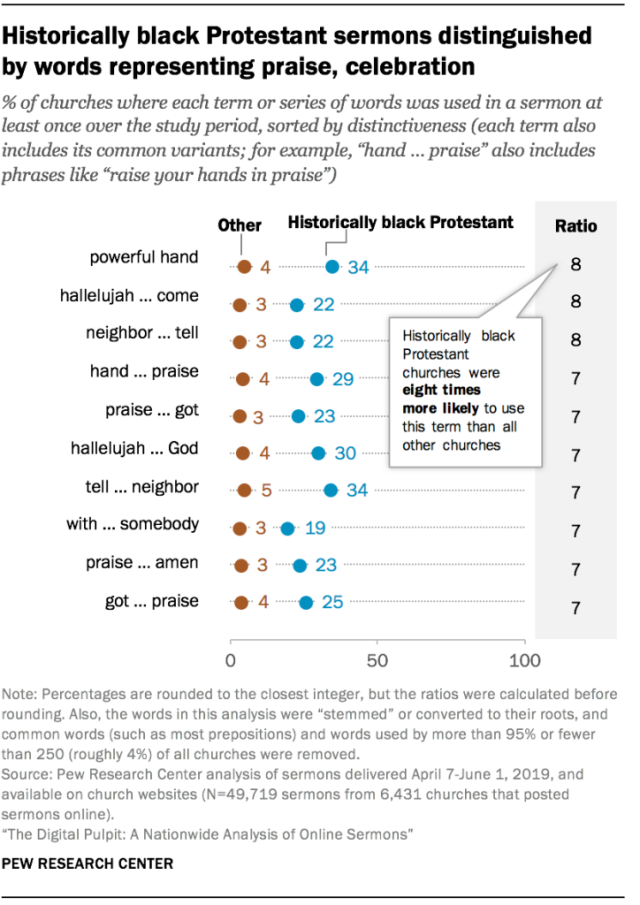

For instance, the distinctive words (or sequences of words) that often appear in sermons delivered at historically black Protestant congregations include “powerful hand” and “hallelujah … come.” The latter phrase (which appears online in actual sentences such as “Hallelujah! Come on … let your praises loose!”) appeared in some form in the sermons of 22% of all historically black Protestant churches across the study period. And these congregations were eight times more likely than others to hear that phrase or a close variant. Although the word “hallelujah” is by no means unique to historically black Protestant services, this analysis indicates that it is a hallmark of black Protestant churches.

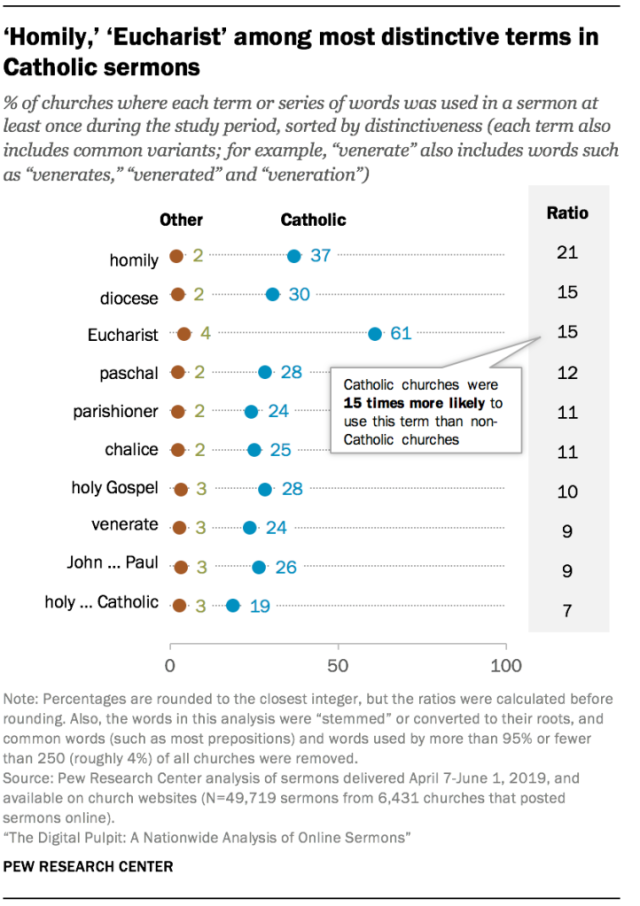

Meanwhile, the distinctive vocabulary of Catholic sermons includes “homily” (which is what Catholics typically call a sermon) as well as “diocese” and “Eucharist.”

The two analytic lenses used in this report

This report uses two different comparison groups depending on the focus of the analysis. Some findings are based on the share of all sermons that have certain characteristics (for example, “61% of sermons reference the name of a book from the Old Testament,” or “the median evangelical Protestant sermon is 39 minutes long.”)

Other findings are based on the share of all churches that have certain characteristics (for example, “37% of all Catholic churches used the word ‘homily’ at least once during the study period.”) These analyses aggregate all sermons delivered at a single church and analyze them together, to represent what a consistent attendee at that church would have heard over the duration of the study period.

The findings about the most common or distinctive words are based on the share of churches, because calculating the share of all sermons that use a particular word would give little indication of whether the word was used across a wide swathe of churches or just many times in a few churches. The findings about the median length of sermons and how often they include citations of books of the Old Testament (the Hebrew Bible) and the New Testament (which includes the Christian Gospels) are based on the content of individual sermons.

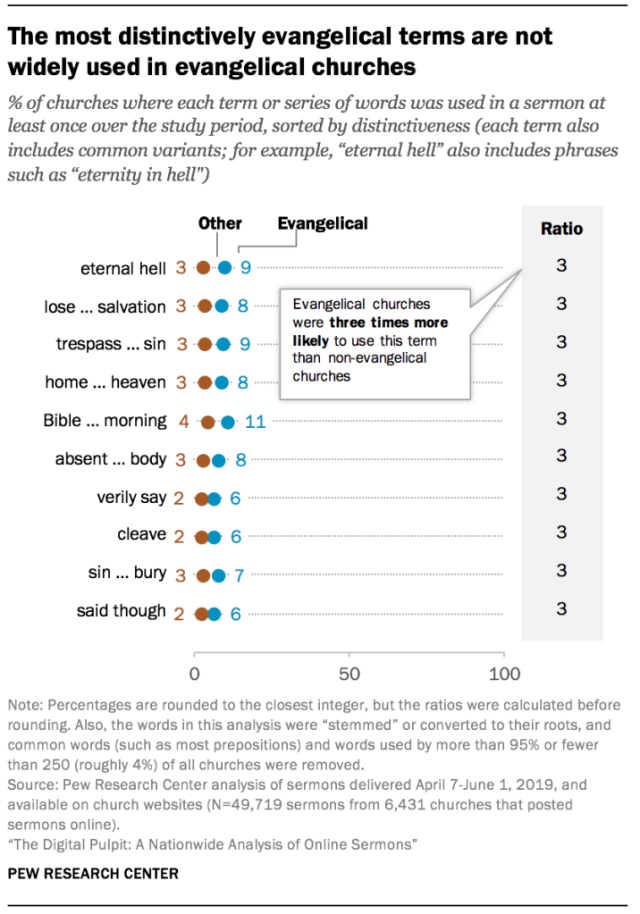

Some terms are distinctive to a religious tradition but are not very common even within that tradition. For example, the three terms most disproportionately used in evangelical sermons include variants of the phrases “eternal hell,” “lose … salvation,” and “trespass … sin” (which appear online in actual sentences such as, “Either allow what he did to pay for your sin, or you are going to pay for your sin in eternity, in hell. That’s the Gospel we have.”). But only one distinctively evangelical phrase (“Bible … morning”) was used in a sermon at more than 10% of evangelical congregations during the study period.

Indeed, a congregant who randomly chose one of the evangelical churches in the study and listened to all the sermons it posted online during the eight-week period would have only a one-in-ten chance of hearing the most distinctive phrase in evangelical sermons – “eternal hell” or a close variant, such as “eternity in hell” – compared with a nearly four-in-ten chance of hearing the most distinctively Catholic term (“homily”) if that listener chose a Catholic church.

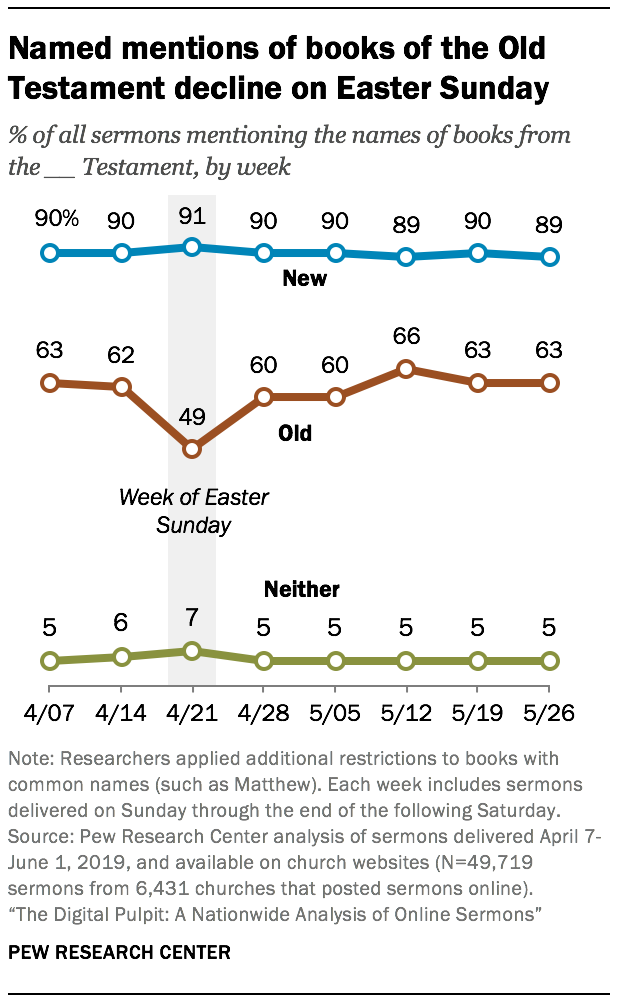

Meanwhile, an analysis of which books of the Bible are cited by name suggests that preachers nationwide, across all major Christian traditions, are more likely to refer to books from the New Testament (90% of all online sermons do so) than the Old Testament (61%).

This pattern is especially pronounced in mainline Protestant and Catholic sermons: These two groups are, respectively, 39 percentage points and 40 percentage points more likely to mention a book of the New Testament than to mention a book of the Old Testament by name in any given sermon. This may reflect the fact that most ministers in the mainline Protestant and Catholic traditions preach on the day’s Gospel reading, which is always from the New Testament.

References to books of the Bible also vary over time. For instance, the share of all sermons that mention a book of the Old Testament by name declined by 13 percentage points on the week of Easter Sunday (to 49% from 62% the previous week) and then rebounded the following week.

These are among the key findings of the Center’s initial foray into analyzing the nature and content of online sermons using computational approaches. For more details on how the database was built and the natural language processing tools used in the analysis, see the Methodology.

In interpreting these findings and the ones that follow, several cautions are warranted:

- The sermons included in this dataset are not necessarily representative of all the sermons delivered in U.S. religious congregations. To begin with, not all congregations are Christian churches. Moreover, not all Christian churches make their sermons publicly available online. And the churches that do place sermons online may choose selectively, posting some but not others.

- The sermons were collected during an eight-week period in 2019 that included Easter. Sermons delivered around Easter may be different, in content as well as in length, from sermons delivered at other times of year.

- Some churches include audio or video recordings of other parts of a worship service – such as Bible readings, hymns and prayers – along with the sermons they post online. If a sermon was posted online along with Bible readings, prayers or music, and without a clear separation, the sermon could be counted by the text processing tools as longer than it actually was.

- By the same token, if a congregation posted only a portion of a worship service online, the parts that were not posted cannot be included in the analysis. For example, if a congregation posted only half of a sermon online, it would be counted as shorter than it really was.

A note on data privacy

All of the sermons analyzed in this report were shared publicly on church websites, or on services – such as YouTube – that were linked from those websites. In some cases, congregational websites made some attempt to prevent the sermons they share online from being viewed or downloaded by nonmembers – for instance, by storing them in a hard-to-reach database or behind a login screen. The Center made absolutely no attempt to access these sermons, even when it would have been possible.

Out of concern for the privacy of congregations and clergy, the data is presented in this report in aggregate form, without citing identifying information such as congregations’ names or addresses.

Nevertheless, the nearly 50,000 sermons collected in this analysis offer a window into the messages that millions of Americans hear from pulpits across the country. The view is limited and does not come close to revealing all the meaningful communications between American clergy and their congregations, but it is an attempt to look systematically and objectively at a large portion of those communications.

This research also builds on earlier computational research on religion, such as a study analyzing the sermons that pastors share in text form on dedicated sermon hosting sites like SermonCentral.com.5 Pew Research Center’s computational analysis brings a new level of comprehensiveness to the study of sermons, beginning with a very large database of U.S. churches – identified using Google Places – and collecting not only sermons that have been posted in plain text form, but also transcribing sermons that were shared in audio and video formats on congregations’ main websites.

The rest of this report takes a closer look at the findings from the new analysis, including differences across major Christian traditions in the content and length of sermons as well as their most common biblical citations.

How Pew Research Center collected and analyzed the online sermons used in this report

To collect the sermons analyzed in this report, data scientists deployed a custom-built computer program (a web scraper) to the public websites of 38,630 American churches. The websites of these churches were identified using the Google Places API. Thus, the churches can be considered representative of all Christian churches with English-language websites listed on Google Maps. Researchers also gathered commercially available information about these churches’ denominations, membership sizes and racial compositions, where possible.

The scraper automatically navigated through the website of each church, using machine learning technology to find any pages with sermons in audio, video or text form. The scraper then downloaded each sermon along with the date it was delivered, and, if necessary, transcribed it from audio to text using automated methods. If churches shared sermons somewhere other than their websites – such as on Facebook accounts or in printed (hard copy) form – those sermons could not be included in this research. Sermons posted to YouTube, Vimeo or common sermon-sharing sites such as SermonAudio.com were collected only if the account was directly linked from the church website.

The resulting database contains the text of 49,719 sermons shared by 6,431 U.S. religious congregations, nearly all of which are Christian churches. All the sermons were delivered between April 7 and June 1, 2019, a period that included some of Lent, Easter Sunday and several weeks following Easter.

Researchers were able to identify a denomination (such as the Southern Baptist Convention), denominational family (for example, Baptist), approximate membership size and predominant race or ethnicity for 5,677 of these 6,431 congregations (88%). Where available, these variables were used to identify each congregation’s religious tradition. U.S. churches belong to a wide range of religious traditions. However, only four broad traditions were numerous enough in the sermons dataset to be analyzed and broken out separately in this report: Catholic, evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant and historically black Protestant.

The final dataset includes sermons publicly posted on the websites of 2,156 evangelical Protestant congregations, 1,367 mainline Protestant congregations, 422 Catholic parishes and 278 historically black Protestant congregations. The remaining congregations could not be reliably classified, belong to other Christian traditions (such as Orthodox Christian denominations) or belong to other faiths; their sermons are not described separately, though they are included in the overall analysis of all sermons online, and they are counted in the total figures.

To the Center’s knowledge, this research is the most exhaustive attempt to date to catalogue and analyze American religious sermons. It is not, however, representative of all sermons delivered in U.S. churches. See the Appendix for more details on how the congregations included in this study differ from congregations nationwide. See the Methodology for additional technical information on how this study was conducted.

Sermon length varies across religious traditions

Among sermons shared in video or audio format in a sufficiently high-quality file that the Center could determine their length, the median sermon in this dataset runs 37 minutes in length.6

However, the length of a typical sermon varies widely among churches in different religious traditions. The median sermon collected from the website of a historically black Protestant church (54 minutes) is more than three times as long as the median Catholic homily (which runs just 14 minutes). Evangelical and mainline Protestant sermons fall somewhere in between: Sermons found on the websites of evangelical churches run a median of 39 minutes, fully 14 minutes longer than those collected from mainline Protestant churches (25 minutes).

These findings largely hold true when word count, rather than duration, is used to measure the length of sermons.7 However, there is one notable exception: Historically black Protestant sermons are roughly as long as evangelical Protestant sermons when measured by word count, but 38% longer when measured by duration. This suggests that there may be more time in sermons delivered at historically black Protestant congregations during which the preacher is not speaking, such as musical interludes, pauses between sentences or call and response with people in the pews.

Sermons share common language, but some terms are distinctive

Certain words and phrases appear consistently across the sermons of all Christian traditions, while other expressions are more commonly used in certain traditions. To conduct this analysis, researchers first stripped each sermon of “stop words” (common pronouns, articles, prepositions and other words with little significance on their own).8

To simplify the analysis and to avoid repeated mentions of similar words or phrases, each remaining word was then converted to its root. For instance, “Bible” and “biblical” would both become “bibl.” As a result, words or phrases that are similar but not identical may be shortened to the same piece of text. The phrases “eternity in hell” and “eternal hell,” for instance, would both be shortened to “etern hell.”

The statistics in this section speak to the share of all churches in which a particular word or phrase appeared in a sermon at least once during the study period, rather than the share of all sermons that contain that term. This is because sermon-level statistics would offer few clues as to whether a particular phrase crops up at least occasionally in a large percentage of churches, or whether that phrase appears in a large number of sermons delivered at a small percentage of all churches.

Across the four largest U.S. Christian traditions, the most commonly used words in online sermons are simple, broadly applicable terms. The three words that appear most frequently in sermons are “say,” “people” and “come” – they are included in nearly every church’s sermons. “Know,” “life” and “like” make the next most frequent appearances, again in nearly all churches in the study. “Jesus” is the 20th most common term, used in sermons at 99% of congregations. These rates vary by only a small margin across Christian traditions. Of the top 20 words, all were used in sermons at more than 90% of churches in each major Christian tradition in this analysis.

In addition to calculating the most common terms across Christian traditions, researchers also identified the words and phrases that congregations of each major Christian tradition were disproportionately likely to hear in sermons, compared with congregations in the other traditions. Researchers identified these “most distinctive” terms by calculating the share of all churches in a Christian group with sermons that used a given word or phrase over the study period, as well as the share of all churches not in that group where the word or phrase was used, and then dividing the former by the latter to establish a ratio. In addition to converting each word to its stem, as in the preceding analysis, researchers removed any words used in sermons at fewer than 250 churches (4%) or at more than 95% of all churches (6,109).

Some of the findings are commonsensical. For instance, Catholic congregations were 21 times more likely than others to hear the term “homily” at least once during the study period, and they were 15 times more likely to hear “diocese” and “Eucharist.”9

In other cases, a tradition’s most distinctive terms may reflect some aspect of its teachings or its lectionary (a calendar of weekly readings). For example, Catholic sermons from the study period are more likely than others to contain the word “paschal,” which refers to Easter and to what the Catholic Catechism calls the “paschal mystery” of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus.

Certain expressions may be distinctive to the sermons of a particular Christian tradition but not especially common even within that tradition. Evangelical sermons are an especially notable example of this phenomenon.

Evangelical sermons contain a number of distinctive words and phrases relating to sin, punishment and redemption. But most of these terms were used in sermons at fewer than 10% of all evangelical churches across the study period. For instance, sermons from evangelical churches were three times more likely than those from other traditions to include the phrase “eternal hell” (or variations such as “eternity in hell). However, a congregant who attended every service at a given evangelical church in the dataset had a roughly one-in-ten chance of hearing one of those terms at least once during the study period. By comparison, that same congregant had a 99% chance of hearing the word “love.”

In addition to being less common overall, the most distinctively evangelical terms also are less distinctive than those of other Christian traditions. For example, evangelical congregations were only three times more likely than others to hear the phrase “eternal hell” in a sermon during the study period, while Catholic congregations were 12 times more likely than others to hear the word “paschal.”

Other distinctively evangelical terms include variations of the phrases “lose … salvation” (used in 8% of all sermons delivered to evangelical congregations over the course of the data collection), “trespass … sin” (9%), and “home … heaven” (8%). In each case, evangelical churches were about three times as likely as others to have these words in their sermons.

Several of the terms that distinguish sermons from historically black Protestant churches include the words “hallelujah” and “neighbor.” Both “neighbor … tell” and “tell … neighbor” rank among the 10 words and phrases most disproportionately used in historically black Protestant sermons. (The actual phrases used in a sermon might be something like “tell your neighbor” but would be shortened in the text processing. Similarly, the exhortation to “lift your hands in praise” would become “hand … praise.”)

The phrase that is most distinctive to historically black Protestant congregations is “powerful hand.” Some 34% of black Protestant churches used some variation of this expression in a sermon during the study period, compared with just 4% of other congregations. Two of the historically black Protestant tradition’s 10 most distinct phrases include the word “hallelujah.”

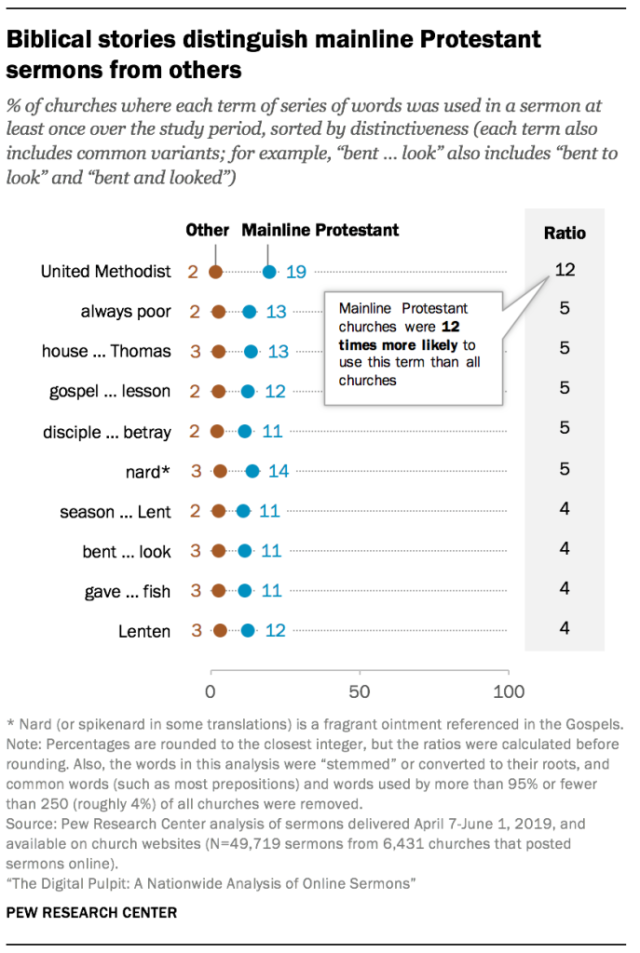

In mainline Protestant churches, the most distinctive phrase is “United Methodist,” which is the name of the largest mainline Protestant denomination in the U.S. This phrase was heard in the sermons of 19% of mainline Protestant congregations during the time period studied. Notably, the 2014 Pew Research Center Religious Landscape Study found that a similar share (about a quarter) of all mainline Protestants belong to the United Methodist Church.

Beyond that, the language that most distinguishes sermons in mainline Protestant churches seems to center around biblical stories. Such phrases include “disciple … betray,” and “bent … look.”

Most sermons mention books from both Old and New Testaments

How Pew Research Center analyzed biblical citations

Researchers identified biblical citations by looking for the names of books, Gospels, or epistles of the Bible. To compile this list of books, the Center used the five versions of the Bible most commonly read aloud in U.S. congregations as of 2012 (excluding congregations that report reading multiple translations), according to the National Congregations Study.

For book names that are not commonly used in other contexts – for instance, “Thessalonians” – researchers simply counted any use of the name. For books such as “John” that have a wider range of uses unrelated to scripture, researchers included extra restrictions to avoid overestimating the rate at which books are cited.

For these books, researchers only included the name if it appeared no further than three words from a one- or two-digit number, the word “book” or “chapter” or its classification in the Bible (such as “epistle” or “Gospel”). These searches were case-insensitive. The word “book” sufficed even for pieces of scripture that are Gospels or epistles.

For example, the phrases “John 14,” “in John chapter 14, verses 1 through 6” and “turn to John, chapter 14” – as well as simply “the Gospel of John” – would all qualify as a mention of the Book of John. “John” alone would not. Books preceded by a volume number (such as II Peter) were counted if preceded by a number (“2 Peter”) or with an ordinal label (“2nd Peter” or “second Peter”).

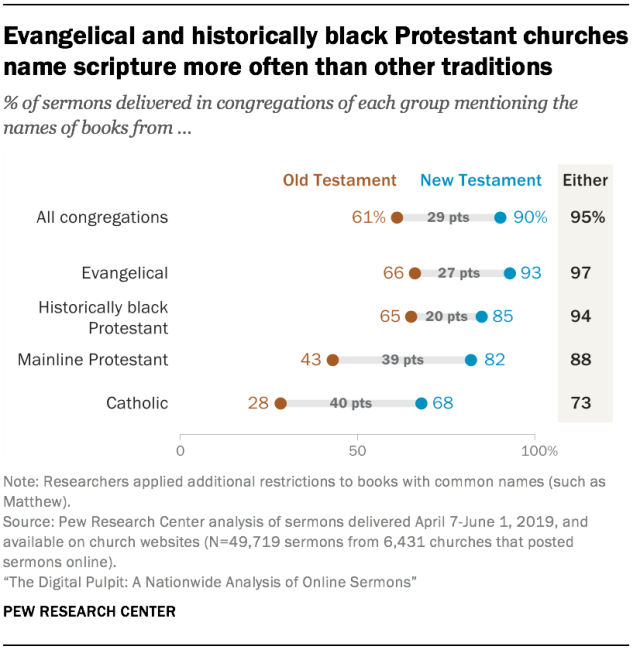

The sermons that American churches share online are heavily laced with scripture: 95% reference at least one book, Gospel or epistle of the Bible by name, and more than half (56%) cite particular books from both the Old Testament (also known as the Hebrew scriptures) and the New Testament (which includes the Christian Gospels) in the same sermon. These numbers vary across Christian groups, with evangelical churches being the most likely to reference a book, Gospel or epistle of the Bible by name – doing so in 97% of all sermons. Pastors across the country are more likely to reference the New Testament by name (90% do so) than to mention the Old Testament (61%).

In contrast to the preceding analysis, this section of the report is based on sermons, rather than churches. Because almost every congregation in the dataset heard at least one sermon that mentioned books from both the New and Old Testaments during the study period, using the percentage of sermons as a frame of reference allows for a more revealing assessment of differences across religious traditions.

In addition, these findings may be influenced by the method used to identify references to the Old and New Testaments, as well as the ways that different churches share elements of their services online. For example, if a Catholic church posted the scripture reading that generally precedes a Catholic homily, the text processing tools would likely count it as naming a particular book of the Bible. But if the leader of a different church referred to those readings by saying, “in our first reading” or “as we heard in our second reading” – without naming the readings themselves – it would not be counted as a citation of a particular book of scripture.

Books from the New Testament are more commonly cited than books from the Old Testament across every Christian group. At least one book from the New Testament is named in 90% of all sermons, while a book of the Old Testament is cited in 61% of sermons.

Clergy in evangelical and historically black Protestant churches mention the names of books from the Old Testament most frequently. Roughly two-thirds of sermons delivered to these congregations mention specific books of the Old Testament, compared with 43% of mainline Protestant sermons and 28% of Catholic homilies.

Catholic and mainline Protestant sermons have the largest gap between references to the New and Old Testaments – sermons from these two groups are, respectively, 40 percentage points and 39 percentage points more likely to reference a book of the New Testament than a book of the Old Testament. Mainline sermons, however, reference scripture more frequently: 88% of all mainline sermons mention the name of at least one book of the Bible, compared with 73% of Catholic homilies that cite a book of the Bible by name.

By comparison, evangelical sermons are 27 percentage points more likely to reference the New Testament (93%) than the Old Testament (66%). Historically black Protestant sermons exhibit the smallest gap, at 20 points (85% vs. 65%).

Evangelical sermons also are the most likely to name a book from both the Old and New Testaments in the same sermon: 62% of all sermons from evangelical churches did so in the study period, compared with 56% of historically black Protestant sermons, 37% of mainline Protestant sermons and 22% of Catholic homilies.

Scripture citations are likely influenced by calendars such as the common lectionary, which specifies which biblical passages should be read during weekly services for many groups. This influence can be seen most clearly on Easter Sunday, which occurred during the third of the study’s eight weeks for most U.S. Christians. Mentions of books from the Old Testament across all Christian groups dropped by 13 points during the week that began on Easter Sunday (to 49% during the week of Easter Sunday from 62% a week earlier) before rebounding the following week. Mentions of books from the New Testament, however, stayed roughly steady throughout the study period.

Smaller churches more likely to cite books of Old Testament by name

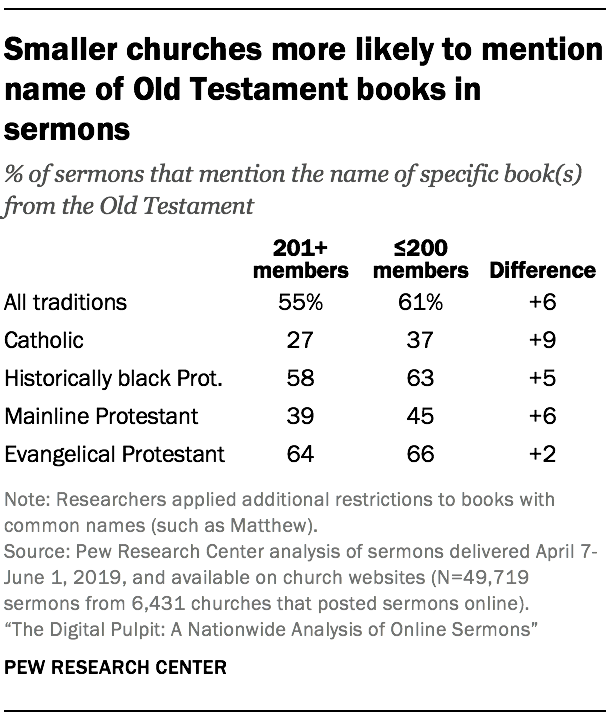

The size of a congregation’s membership also is somewhat related to whether its sermons mention books of the Bible by name. But to the extent that differences exist between smaller and larger congregations, they tend to be dwarfed by the effect of that church’s Christian tradition (for example, evangelical or mainline).

For example, pastors at churches with 200 or fewer members cited specific books from the Old Testament in 6% more of their sermons, on average, than those at churches with more than 200 members. This tendency generally holds true within Christian traditions: For instance, smaller mainline congregations heard a reference to the Old Testament in 45% of their sermons, compared with 39% at larger mainline churches during the study period.

CORRECTION: (Jan. 27, 2020): In the chart “Christian traditions share common language, but also possess their own distinctive phrases,” the “evangelical” column has been edited to correct for a data tabulation error. Changes did not affect the report’s substantive findings.