This study is Pew Research Center’s most comprehensive, in-depth attempt to explore religion among Black Americans. Its centerpiece is a nationally representative survey of 8,660 Black adults (ages 18 and older), featuring questions designed to examine Black religious experiences. The sample consists of a wide range of adults who identify as Black or African American, including some who identify as both Black and Hispanic or Black and another race (such as Black and White, or Black and Asian).

The Center recruited such a large sample in order to examine the diversity of the U.S. Black population. For example, this study is able to compare the views and experiences of U.S.-born Black Americans with those of Black immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean. It can compare Black adults born before 1946 (the Silent Generation and a very small number of those in the Greatest Generation) with Black adults born after 1996 (Generation Z). Because the study focuses on faith among Black Americans, it also examines Protestants who attend Black churches, Protestants who attend churches where the majority is White or another race, Protestants who attend multiracial churches, Black Catholics, Black members of non-Christian faiths and Black Americans who are religiously unaffiliated (identifying as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular).

The survey was complemented by guided, small-group discussions with Black adults of various ages and religious leanings, as well as in-depth interviews with Black clergy. These gave Black religious leaders, lay believers and nonbelievers an opportunity to describe their religious experiences in their own words.

Survey respondents were recruited from four nationally representative sources: Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (conducted online), NORC’s AmeriSpeak panel (conducted online or by phone), Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel (conducted online) and a national cross-sectional survey by Pew Research Center (conducted online and by mail). Responses were collected from Nov. 19, 2019, to June 3, 2020, but most respondents completed the survey between Jan. 21 and Feb. 10, 2020. For more information, see the Methodology for this report. The exact wording of the questions used in this analysis can be found here.

Throughout this report, Black churches and congregations are defined as those where the respondent said that all or most attendees are Black and the senior religious leaders are Black. White or other race churches and congregations are those where the respondent said that either most attendees are White; most attendees are Asian; most attendees are Hispanic; or most attendees are of a different (non-Black) race, and the same is true of the senior religious leaders. Multiracial churches and congregations are primarily those where the respondent said that no single race comprises a majority of attendees – regardless of the race of the religious leaders. This category also includes smaller numbers of congregations where the majority of the congregation is not Black, but senior religious leaders are Black; congregations where all or most attendees are Black but the senior religious leaders are not; and congregations where the senior religious leadership is multiracial – regardless of the race of the congregation.

In tables and text that analyze survey findings on Black Protestants and Catholics, the category “other Christians” refers to a group composed mostly of Jehovah’s Witnesses, but also Orthodox Christians, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as Mormons) and other groups. In the category “non-Christian faiths” the largest single group is Muslims, but this category also includes people who describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” as well as Buddhists, Jews and adherents of traditional African or Afro-Caribbean religions.

In tables and text that analyze survey findings by generation, members of Generation Z are respondents who were born from 1997 to 2002, Millennials from 1981 to 1996, members of Generation X from 1965 to 1980, Baby Boomers from 1946 to 1964, and members of the Silent Generation prior to 1946 (in this report, the Silent Generation category includes a very small number of those in the Greatest Generation, who were born before 1928).

“Black, non-Hispanic” respondents are those who identify as single-race Black and say they have no Hispanic background. “Black Hispanic” respondents are those who are Black and also say they do have Hispanic background. “Multiracial” respondents are those who indicate two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Black) and say they have no Hispanic background.

“African-born” respondents were born in sub-Saharan Africa, while “Caribbean-born” respondents were born in the West Indies. In this report, “immigrant” refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens.

Religion has long figured prominently in the lives of Black Americans. When segregation was the law of the land, Black churches – and later, mosques – served as important spaces for racial solidarity and civic activity, and faith more broadly was a source of hope and inspiration.

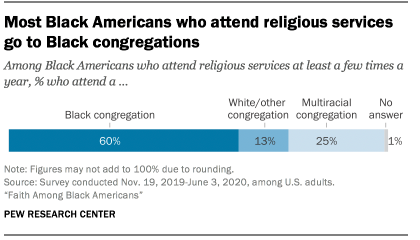

Today, most Black adults say they rely on prayer to help make major decisions, and view opposing racism as essential to their religious faith. Also, predominantly Black places of worship continue to have a considerable presence in the lives of Black Americans: Fully 60% of Black adults who go to religious services – whether every week or just a few times a year – say they attend religious services at places where most or all of the other attendees, as well as the senior clergy, are also Black, according to a major new Pew Research Center survey. Far fewer attend houses of worship with multiracial congregations or clergy (25%) or congregations that are predominantly White or another race or ethnicity, such as Hispanic or Asian (13%).

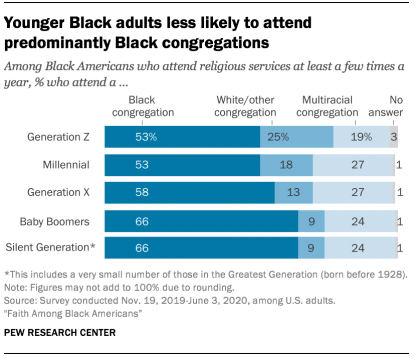

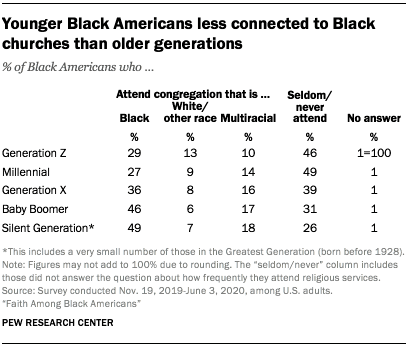

But these patterns appear to be changing. The survey of more than 8,600 Black adults (ages 18 and older) across the United States finds that young Black adults are less religious and less engaged in Black churches than older generations. Black Millennials and members of Generation Z are less likely to rely on prayer, less likely to have grown up in Black churches and less likely to say religion is an important part of their lives. Fewer attend religious services, and those who do attend are less likely to go to a predominantly Black congregation.

For example, roughly half of Black Gen Zers (born after 1996) who go to a church or other house of worship say their congregation and clergy are mostly Black, compared with two-thirds of Black Baby Boomers and members of the Silent Generation who say this.

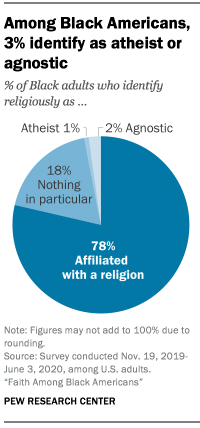

Protestantism has long dominated the Black American religious landscape, and still does. The survey shows that two-thirds of Black Americans (66%) are Protestant, 6% are Catholic and 3% identify with other Christian faiths – mostly Jehovah’s Witnesses. Another 3% belong to non-Christian faiths, the most common of which is Islam.1

But about one-in-five Black Americans (21%) are not affiliated with any religion and instead identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” and this phenomenon is increasing by generation: Roughly three-in-ten Black Gen Zers (28%) and Millennials (33%) in the survey are religiously unaffiliated, compared with just 11% of Baby Boomers and 5% of those in the Silent Generation.

Defining Black congregations

To help analyze survey data, this report splits Black Protestants’ places of worship into three categories – (1) Black congregations, (2) White or other race congregations, (3) and multiracial congregations – based on the respondent’s description of their congregation and clergy.

Black churches/congregations are those where the respondent said that all or most attendees are Black and the senior religious leaders are Black.

White or other race churches/

congregations are those where the respondent said that most attendees are White, most are Asian, most are Hispanic, or most are of a different (non-Black) race, AND most or all of the senior religious leaders are of the same non-Black race as one another.

Multiracial churches/congregations are primarily those where the respondent said that no single race makes up a majority of attendees. This category also includes smaller numbers of congregations where the majority of the congregation is not Black, but senior religious leader(s) are Black; congregations where all or most attendees are Black, but the senior religious leaders are not; and congregations where the senior religious leadership is multiracial, regardless of the race of the congregation.

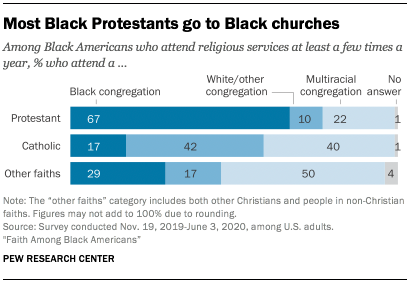

Black Protestants are particularly likely to worship in congregations where most of the laypeople, as well as the senior clergy, are Black. Two-thirds of Black Protestant churchgoers say they attend this type of congregation. By contrast, majorities of Black Catholics and Black adults of other faiths say their congregations and religious leaders are multiracial, mostly White, or mostly some other race.

Nonetheless, there is a broad consensus among Black Americans of all faiths that predominantly Black churches have played a valuable role in the struggle for racial equality in U.S. society. Roughly three-quarters of Black adults surveyed say that Black churches have played at least “some” role in helping Black people move toward equality – including three-in-ten who say Black churches have done “a great deal” – while roughly half say Black Muslim organizations such as the Nation of Islam have contributed at least some in this regard. (See Chapter 10 for more on the history of religion among Black Americans.)

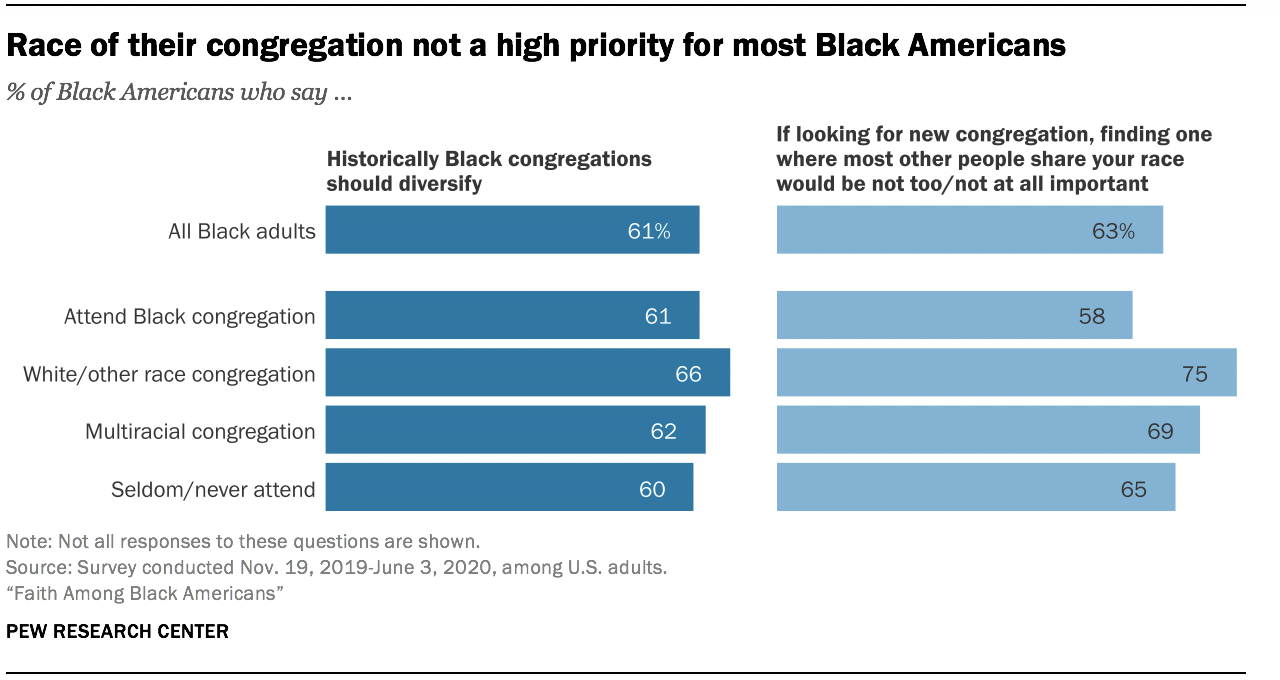

That so many Black Americans worship in Black congregations – and value their role in seeking equal rights – suggests that preserving them as institutions might be a high priority. Yet just a third (33%) of Black Americans say historically Black congregations should preserve their traditional racial character. Most (61%) say these congregations should become more racially and ethnically diverse. This is the majority view among those who attend Black congregations as well as those who do not.

Furthermore, while 34% of Black Americans say that if they were looking for a new congregation, it would be “very important” or “somewhat important” for them to find a congregation where most other attendees shared their race, most (63%) say this would be either “not too important” or “not at all important.” Higher priorities include finding a congregation that is welcoming and that offers inspiring sermons. Again, this pattern holds regardless of whether respondents currently attend a predominantly Black congregation.

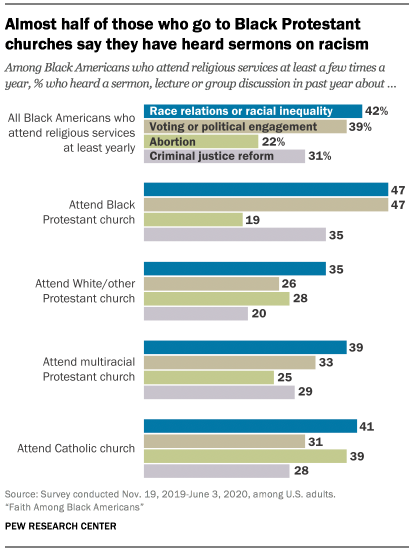

If most Black Americans say these congregations should diversify and the race of other attendees isn’t a top priority to them, what leads so many Black Americans to attend predominantly Black congregations?2 The survey indicates that Black congregations are distinctive in numerous ways beyond just their racial makeup. Sermons are a prime example: Black Americans who attend Black Protestant churches are more likely to say they hear messages from the pulpit about certain topics – such as race relations and criminal justice reform – than are Black Protestant churchgoers who attend multiracial, White or other race churches. And Protestants who go to Black congregations are somewhat less likely than others to have recently heard a sermon, lecture or group discussion about abortion.

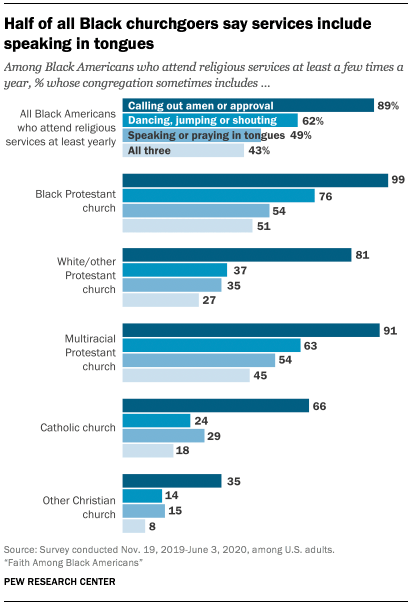

Black churches also have a distinctive atmosphere for worship. Protestants who worship in predominantly Black churches are more likely than other Black Americans to say their congregations feature worshippers calling out “amen” or other expressions of approval (known as call and response). They also are more likely to feature expressive forms of worship that include spontaneous dancing, jumping or shouting. And 54% of Protestants in Black congregations say the services they attend feature speaking or praying in tongues, a practice associated with Pentecostalism.

Taken as a whole, about half of congregants who attend Black Protestant churches report that the services they attend feature all three of these practices at least some of the time, compared with roughly a quarter of Black Protestants in White or other race churches and 18% of Black Catholics.

These are among the key findings of a survey of 8,660 Black Americans, conducted from Nov. 19, 2019, to June 3, 2020.3 While previous surveys on religion have included small or medium-sized samples of Black respondents, and other surveys with larger samples have asked questions about religion as one of multiple topics, this is Pew Research Center’s first large-scale, nationally representative survey designed primarily to help understand distinctive aspects of Black Americans’ religious lives. For more information on how the survey was conducted, see the Methodology.

This report is the first in a series of Pew Research Center studies focused on describing the rich diversity of Black people in the United States. The survey included not only single-race, U.S.-born African Americans but also Americans who identify as both Black and some other race or Black and Hispanic, as well as Black people who live in the U.S. but were born outside of the country.

Many findings in this survey highlight the distinctiveness and vibrancy of Black congregations, demonstrating that the collective entity some observers and participants have called “the Black Church” is alive and well in America today.4 But there also are some signs of decline, such as the gap between the shares of young adults and those in older generations who attend predominantly Black houses of worship. This gap is a result of two distinct pressures.

First, younger Black Americans, like younger Americans more generally, are less religious than their elders. Black Millennials (49%) and members of Generation Z (46%) are about twice as likely as Black members of the Silent Generation (26%) to say they seldom or never attend religious services at any congregation. Second, among Black adults who do attend religious services, the youngest adults are less apt to attend Black congregations than the oldest adults. Among Black Gen Zers who attend religious services at least yearly, about half (just 29% of all Black Gen Zers) say they go to a Black congregation. By contrast, among Black Americans in the Silent Generation who attend religious services at least yearly, fully two-thirds (which is 49% of all Black Americans in the Silent Generation cohort) attend Black congregations.

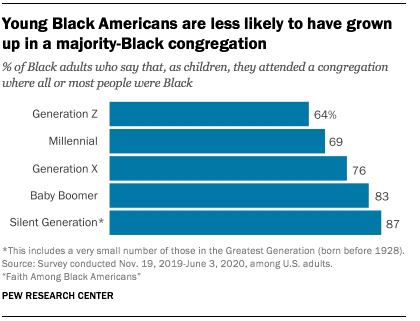

Additional findings suggest that, over the long term, fewer Black families with children have been going to Black congregations. While nearly nine-in-ten members of the Silent Generation (87%) say they grew up attending religious services at a congregation where most or all other attendees were Black, a smaller majority (64%) of Generation Zers say this about their more recent childhoods.

When asked to assess the influence of predominantly Black churches in their communities, nearly half of Black adults (47%) say that Black churches are less influential today than they were 50 years ago. Three-in-ten say they are more influential, and about one-in-five say they hold the same amount of sway.

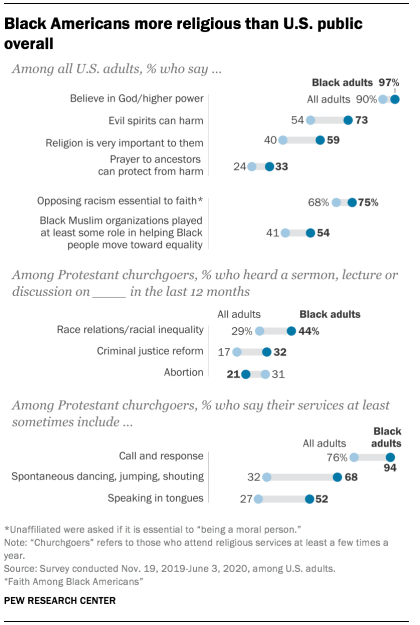

Black Americans more religious than the U.S. public overall

In conjunction with this study, researchers also asked some of the same questions of 4,574 Americans who do notidentify as Black or African American. The findings show that Black Americans are more religious than the American public as a whole on a range of measures of religious commitment. For example, they are more likely to say they believe in God or a higher power, and to report that they attend religious services regularly. They also are more likely to say religion is “very important” in their lives and to be affiliated with a religion, and to believe prayers to ancestors have protective power and that evil spirits can cause problems in a person’s life.

In addition to being more religious by these measures, Black Americans’ views on other topics involving religion or religious groups differ from those of the general population. For example, Black Americans are more likely than Americans overall to view opposition to racism as essential to what it means to be a religiously faithful or moral person.5 And they are more likely to credit predominantly Black Muslim organizations, such as the Nation of Islam, with a role in helping Black people move toward equality in the U.S.

Black Protestants stand out from Protestant churchgoers of other races. Black Protestants are far more likely to go to a church that has highly expressive worship that includes shouts of “amen,” spontaneous dancing, jumping or shouting, and speaking in tongues. And they are less likely than U.S. Protestants overall to report hearing sermons on abortion, but more likely to say they have heard sermons about race relations or criminal justice reform. (While most respondents participated in this survey in early 2020 – prior to May 2020, when a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd, sparking nationwide protests – more recent polling from July 2020 supports this pattern, showing Black Protestants to be far more likely than Protestants of other races to have recently heard sermons supporting the Black Lives Matter movement.)

Religiously unaffiliated Black Americans

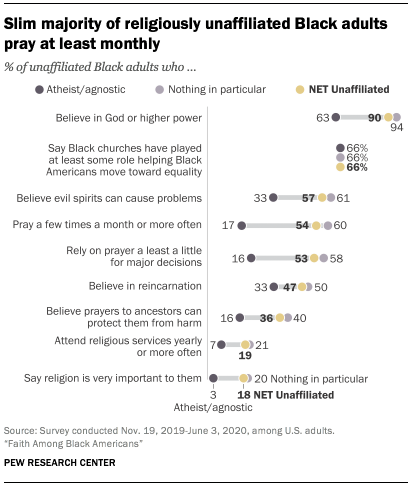

As is true within the general U.S. population, the share of people who do not identify with any religion is increasing among Black Americans. This religiously unaffiliated category (sometimes called religious “nones”) includes those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” when asked about their religion. Most Black religious “nones” (18% of all Black Americans) identify as “nothing in particular,” while far fewer describe themselves as agnostic (2%) or atheist (1%). The survey finds, furthermore, that many Black religious “nones” hold favorable views about Black churches and show numerous signs of religious or spiritual engagement.

For example, most religiously unaffiliated Black Americans credit Black churches with helping Black Americans move toward equality. This is true whether they identify as “nothing in particular” (66%) or as atheist or agnostic (also 66%). (Because so few Black Americans identify as atheist or agnostic, the two groups are analyzed together throughout this report.) In addition, most Black religious “nones” say that predominantly Black churches today have either “too little” influence in Black communities (35%) or “about the right amount of influence” (43%). Just one-in-five (19%) say predominantly Black churches have “too much influence.”

Several religious beliefs and practices are common among Black “nones.” Nine-in-ten say they believe in God or a higher power.6 Just over half report praying at least a few times a month. Similar shares say they rely, at least a little, on prayer and personal religious reflection when making major life decisions, and that they believe evil spirits can cause problems in a person’s life. About half of Black religious “nones” say they believe in reincarnation, and a little more than a third believe that prayers to ancestors can protect them from harm.

By these measures, religiously unaffiliated Black adults are a lot more religious than unaffiliated adults in the U.S. general population. For example, they are more likely to believe in God or a higher power (90% vs. 72%) and to pray at least a few times a month (54% vs. 28%).

Religion and gender

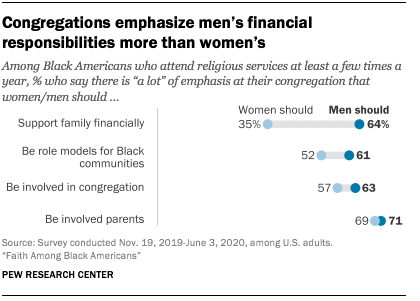

Women make up a small minority of religious leaders at Black Protestant churches, according to the National Congregations Study, and media accounts suggest it is uncommon for women to be named to lead large Black congregations.7 Yet the survey shows that the vast majority of Black Americans – women (87%) and men (84%) alike – say women should be allowed to serve as senior religious leaders of congregations.

Black Americans also typically express egalitarian views on other issues relating to gender norms. For example, among men and women and across religious groups, most say they believe that mothers and fathers who live in the same household should share parenting and financial responsibilities equally.

In addition, Black Americans are almost as likely to say opposing sexism is essential to what it means to be a faithful or moral person as they are to say the same about opposing racism – and, again, men and women are equally likely to report this view.

However, other survey findings suggest that the culture at many Black congregations emphasizes men’s experiences and leadership more than women’s. Black Americans are much less likely to have heard sermons, lectures or group discussions about discrimination against women or sexism than about racial discrimination. In addition, Black Americans are much more likely to say their congregations strongly emphasize that men should financially support their families and be role models in Black communities than to say that they emphasize these same things for women. In fact, of the four roles asked about in the survey, the only one that congregants say is emphasized equally for men and women is being an involved parent.

Though gender is a key focus throughout the report, Chapter 7 looks specifically at the intersection of gender, sexuality and religion in more detail.

African and Caribbean immigrants

One advantage of surveying a large sample of Black Americans is that it is possible to analyze the views of the growing share of Black Americans who are immigrants to the U.S.

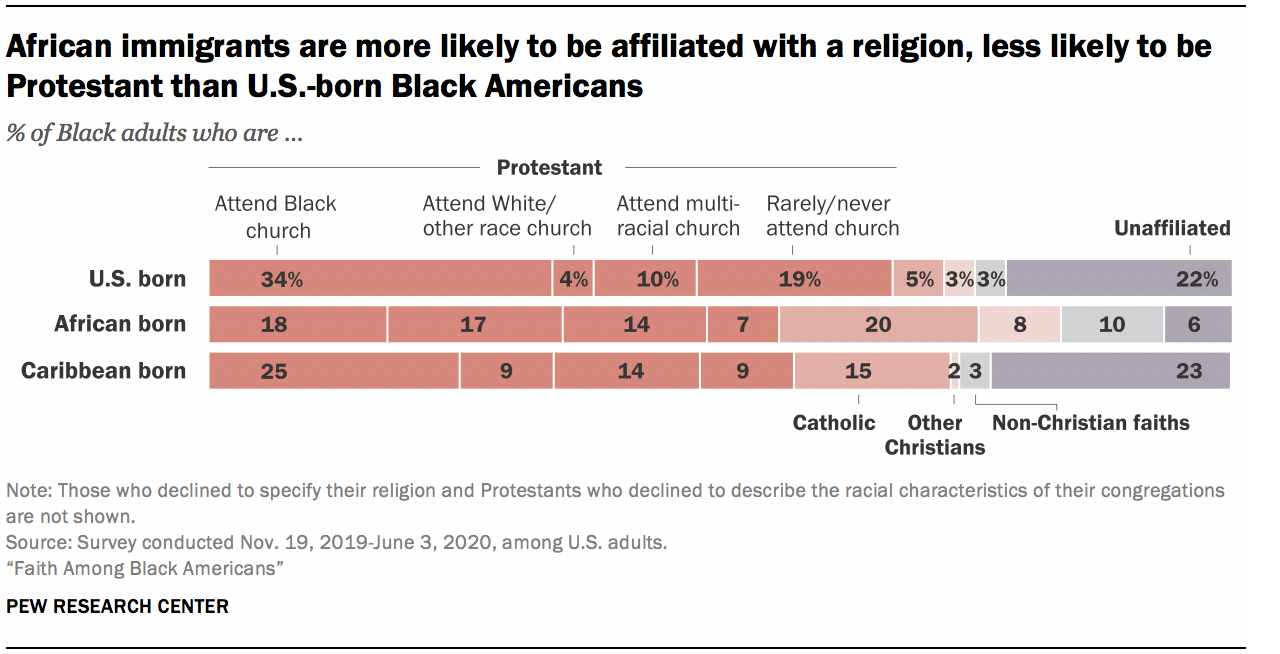

Immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa make up 5% of the Black adult population, and they stand out in the survey findings in numerous ways for more active religious behavior and more conservative social views.8

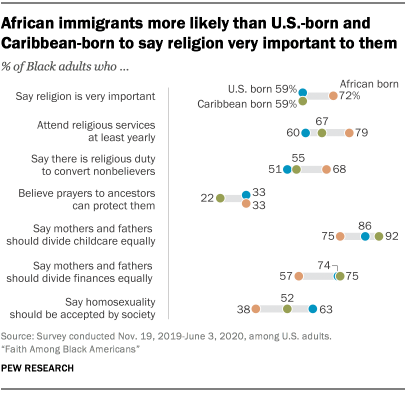

Only 6% of all African immigrants are religiously unaffiliated, far fewer than the share of U.S.-born Black adults who are unaffiliated. African immigrants are less likely to identify as Protestant than are U.S.-born Black Americans, and more likely to identify as Catholic or with non-Christian faiths. African immigrants also are more likely than other Black Americans to say religion is very important in their lives, to report that they attend religious services regularly, and to believe that people of faith have a religious duty to convert nonbelievers.

African immigrants also tend to be more supportive of traditional gender norms than U.S.-born Black adults. For example, they are more likely to say that mothers should be most responsible for taking care of children and that fathers should be most responsible for providing for the family financially – though the prevailing opinion is still that both parents should be equally responsible for both functions. In addition, African immigrants are much less likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted by society.

A slightly larger share of Black adults were born in the Caribbean (6%). Like African immigrants, Black Americans from the Caribbean are more likely than U.S.-born Black adults to be Catholic, though they are about equally likely to be religiously unaffiliated. Caribbean-born immigrants are no more likely than U.S.-born Black Americans to say religion is very important in their lives or that they have a religious duty to convert nonbelievers.

Political partisanship

Most Black Americans (84%) are Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party. Just 10% say they are Republicans or lean Republican.

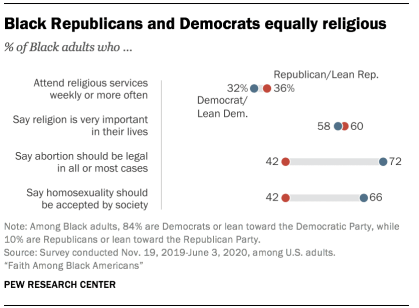

In several ways, the religious lives of Black Democrats and Republicans are similar. They are about equally likely to identify with a religion, to say religion is very important in their lives and to attend religious services at least once a week. The lack of a partisan divide on these measures of religious commitment contrasts with patterns seen among White Americans; White Republicans tend to be more religious than White Democrats.

Though they have similar rates of attendance, there are some differences between Black Democrats and Black Republicans when it comes to the types of congregations they attend. Fewer than half of Black Republicans who attend religious services go to a Black congregation (43%), compared with 64% of Black Democrats. And Black Republicans are more likely than Black Democrats to go to congregations where most attendees are White (22% vs. 11%).

In addition, as in the larger public, Black Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say that abortion should be legal and that homosexuality should be accepted by society. And among Black Christians, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say that opposing racism and racial discrimination, as well as opposing sexism or discrimination against women, are essential to what being a Christian means to them – though more than half of all Black Christians in both parties say these are essential.

Roadmap to the report

The remainder of this report explores these and other findings in more detail. Chapter 1 describes six focus group discussions and highlights some of the reasons Black Americans value Black congregations. Chapter 2 examines the religious affiliations of Black Americans in more detail. Chapter 3 explores some common Christian beliefs as well as other forms of spirituality among Black Americans. Chapter 4 reports how frequently Black Americans engage in a range of religious and spiritual practices. Chapter 5 examines the impact that religion and church have on the everyday lives of Black Americans. Chapter 6 looks more closely at the role race plays in the religious experience of Black Americans. Chapter 7 analyzes views on gender and sexuality and how they are related to religion. Chapter 8 describes how political preferences, engagement and views on social and political topics vary across different types of congregations. Chapter 9 summarizes interviews with 30 Black Protestant clergy from around the country about issues affecting their churches. And Chapter 10 offers a brief overview of Black religious history in the United States, with an emphasis on efforts by religious groups to deal with racism and its effects.