Majorities of U.S. adults say they believe in heaven, hell

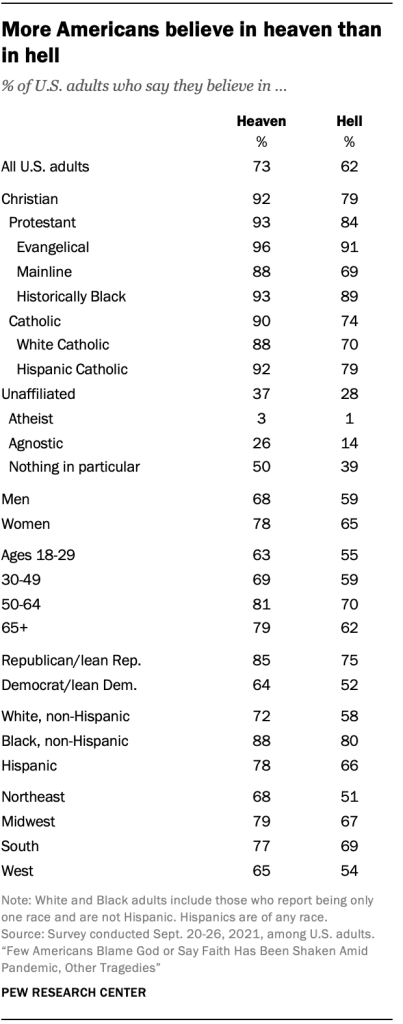

Nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults say they believe in heaven. (The survey did not immediately offer a definition of heaven, though subsequent questions explored what respondents think heaven is like.)

Large majorities of all Christian subgroups say they believe in heaven, while belief is much less common among religiously unaffiliated Americans (37%). This unaffiliated group includes those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” – half of whom believe in heaven – as well as agnostics (26% of whom believe in heaven) and atheists (3%).

While most U.S. adults also believe in hell, this belief is less widespread than belief in heaven. Roughly six-in-ten American adults (62%) say they believe in hell, though once again there are notable differences across subgroups of the population.

Across most Christian subgroups, smaller shares say they believe in hell than heaven. While roughly nine-in-ten Protestants in the evangelical and historically Black traditions believe in hell, only about seven-in-ten mainline Protestants (69%) and 74% of Catholics share this belief.

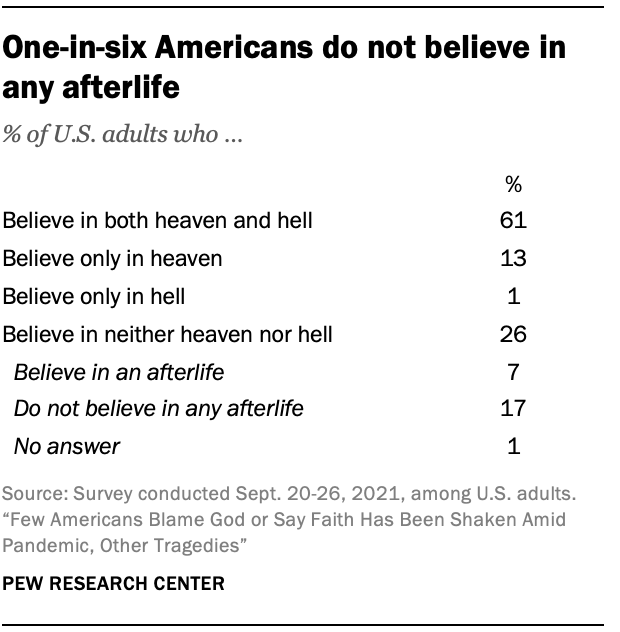

Roughly a quarter of all U.S. adults (26%) say that they do not believe in heaven or hell, including 7% who say they do believe in some kind of afterlife and 17% who do not believe in any afterlife at all.

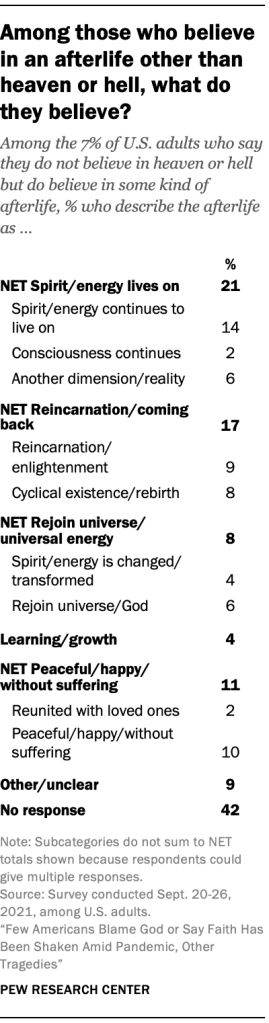

Respondents who believe in neither heaven nor hell but do still believe in an afterlife were given the opportunity to describe their idea of this afterlife in the form of an open-ended question that asked: “In your own words, what do you think the afterlife is like?”

Within this group, about one-in-five people (21%) express belief in an afterlife where one’s spirit, consciousness or energy lives on after their physical body has passed away, or in a continued existence in an alternate dimension or reality. One respondent describes their view as “a resting place for our spirits and energy. I don’t think it’s like the traditional view of heaven but I’m also not sure that death is the end.” And another says, “I believe that life continues and after my current life is done, I will go on in some other form. It won’t be me, as in my traits and personality, but something of me will carry on.”

An additional 17% of respondents who believe in neither heaven nor hell (but do believe in some kind of afterlife) express a belief in people enduring a cyclical existence or becoming enlightened after death. As one individual puts it, “Maybe something like nirvana or enlightenment? I like to imagine that the living world we inhabit is like a cradle for the soul. We spend our lifetime (or maybe many lifetimes) learning and growing, and then in the afterlife we retain all those memories from our life(/lives), and the lessons we’ve learned, and that we exist for some greater purpose that living prepares us for.”

Among many other responses, some people believe that people’s energy rejoins the universe in some form, while others feel that people simply enter a period of peace without suffering. And many people in this group (42% of everyone who says they believe in an afterlife but not in heaven or hell) did not offer a response.

Believers largely see heaven as free from suffering, hell as just the opposite

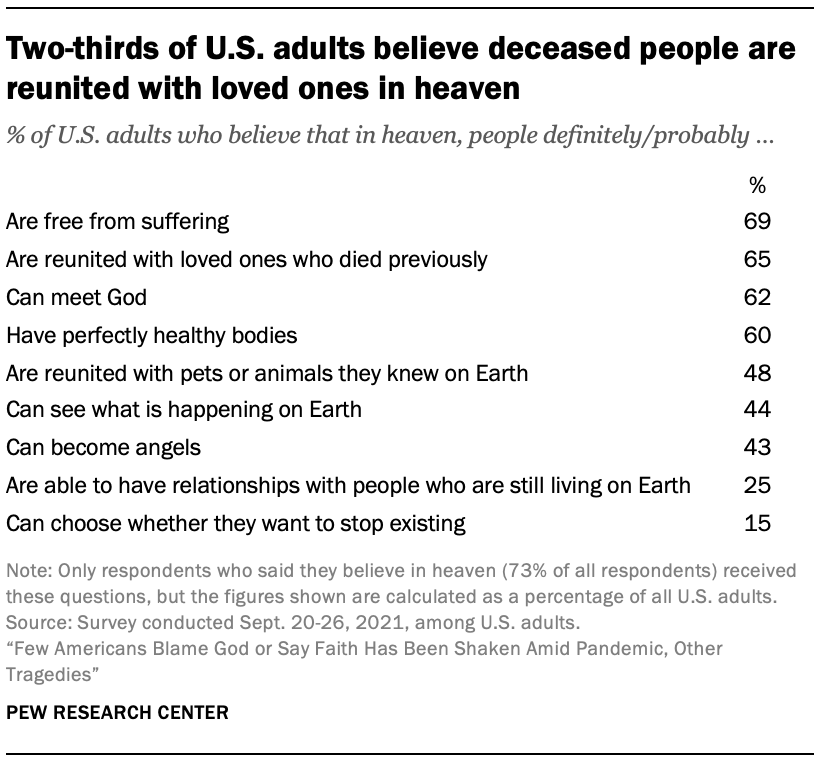

In addition to asking about general belief in heaven and hell, the survey asked about specific characteristics of these two destinations to determine what Americans think they are like. In the case of heaven, respondents were presented with nine prospective traits, and asked whether heaven is “definitely like this,” “probably like this,” “probably not like this” or “definitely not like this.”

Of the items listed, U.S. adults are most likely to say that in heaven, people are definitely or probably free from suffering, with roughly seven-in-ten members of the general public holding this view. This perspective is nearly unanimous among the 73% of Americans who express belief in heaven.

Majorities of Americans also express confidence in the ideas that in heaven, people are reunited with deceased loved ones (65% of all U.S. adults say this), can meet God (62%) and have perfectly healthy bodies (60%). Roughly half of all U.S. adults (48%) believe that people in heaven are reunited with pets or animals that they knew on Earth, while more than four-in-ten say that people in heaven can see what is happening on Earth (44%) and can become angels (43%).

Smaller shares believe that people in heaven are able to have relationships with people who are still living on Earth (25%), or that they can choose whether they want to stop existing (15%).

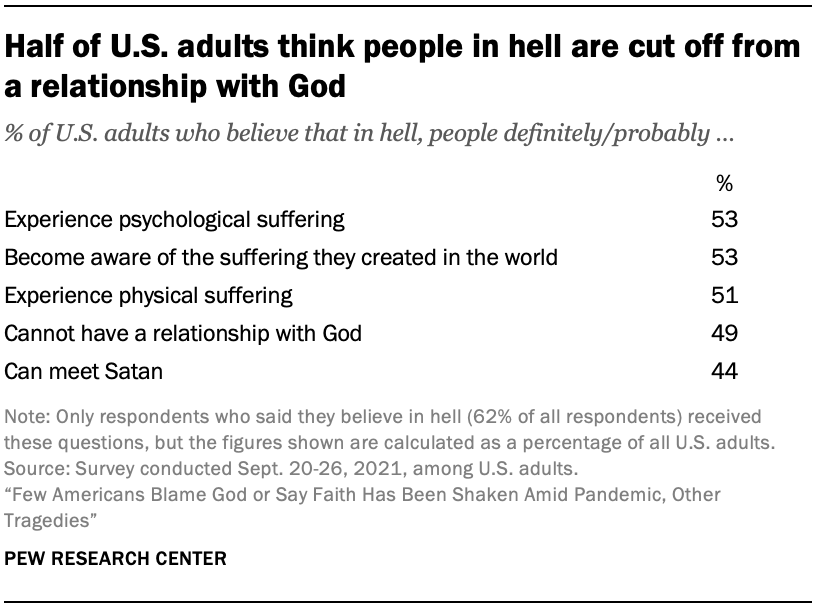

In the case of hell, the survey asked about five different traits. About half of all U.S. adults – the vast majority of the 62% who believe in hell – say that people in hell definitely or probably experience psychological suffering, become aware of the suffering they created in the world, experience physical suffering, and are prevented from having a relationship with God. A slightly smaller share (44%) say they believe people in hell definitely or probably can meet Satan.

Who can get to heaven? No consensus on whether belief in God, being Christian is required

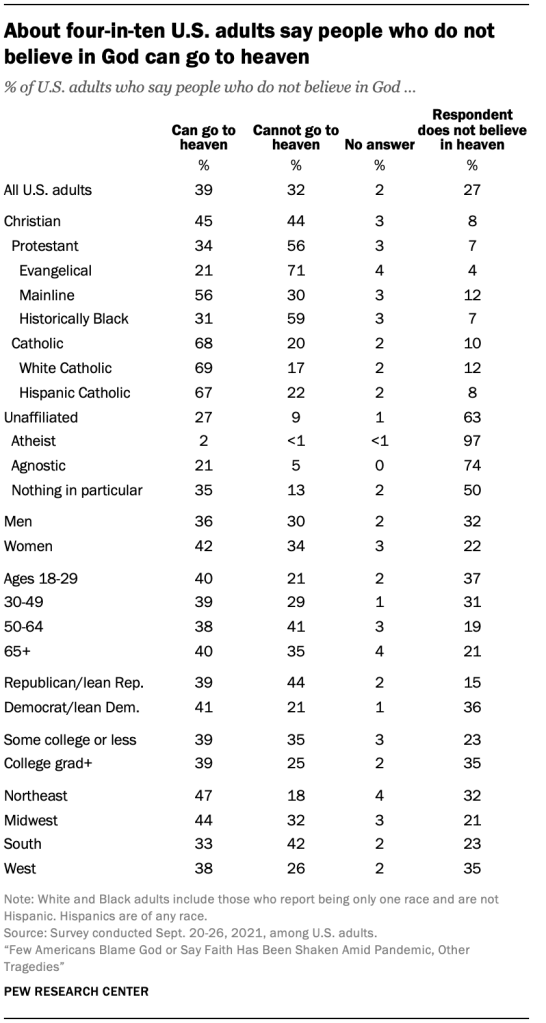

While most U.S. adults believe in heaven, there is disagreement about who can go there. Among all Americans, about four-in-ten (39%) say that people who do not believe in God can go to heaven, while roughly a third (32%) say that nonbelievers cannot enter heaven. (Again, 27% do not believe in heaven at all.)

Catholics are twice as likely as Protestants to say that people who do not believe in God can still go to heaven (68% vs. 34%). Evangelical Protestants are especially likely to view access to heaven as exclusive in this regard, with 71% saying that only those who believe in God can go to heaven, compared with 21% who say nonbelievers can gain entry. A majority of members of the historically Black Protestant tradition (59%) also say that nonbelievers are excluded from heaven, while most mainline Protestants (56%) say that people who do not believe in God can go to heaven.

Most religious “nones” do not believe in heaven at all, but those who do are much more likely to say that people who do not believe in God can go to heaven (27% of all religious “nones”) than that they cannot (9%).

More than four-in-ten Republicans (44%) believe in heaven and say that people who do not believe in God cannot go there – twice the share of Democrats who hold the same view (21%). Additionally, Americans who live in the South are more likely than those in other regions to believe in heaven and to say that people who do not believe in God are excluded.

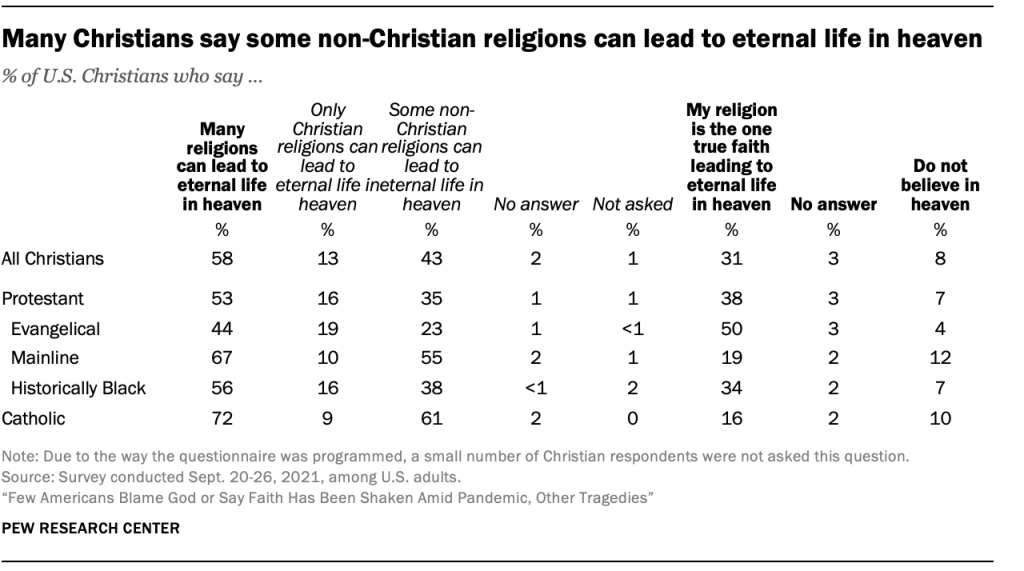

About three-in-ten U.S. Christians (31%) say that their religion is the one true faith leading to eternal life in heaven, while nearly twice as many (58%) say that there are multiple religions that can lead to heaven.

Once again, there are differences on this question across subgroups – including between Protestants and Catholics. Roughly four-in-ten Protestants (38%) say that theirs is the only faith leading to eternal life in heaven, a view that is especially common among evangelical Protestants (50%). Among Catholics, meanwhile, just 16% say that their religion is the one true faith leading to eternal life in heaven, while about seven-in-ten (72%) instead say that many religions can lead to eternal life.1

Christians who believe that many religions can lead to eternal life in heaven were asked whether they believe that this privilege is reserved only for members of other Christian religions, or that some non-Christian religions can also lead to eternal life in heaven. Among all Christians, a majority (58%) say that many religions can lead to eternal life in heaven, and within this group, the prevailing view is that members of some non-Christian religions are able to attain eternal life in heaven (43% of all Christians express this view). Just 13% of U.S. Christians say that many religions can lead to eternal life in heaven, but that only Christian religions qualify.

Catholics are more likely than Protestants to say that many religions can lead to heaven and that non-Christians are included (61% vs. 35%), although most mainline Protestants (55%) also say this. Members of the evangelical and historically Black Protestant traditions, however, are more likely to say either that theirs is the one true faith leading to eternal life in heaven or that only Christian religions can lead to heaven.

Fewer than half of Americans believe in reincarnation, fate

The survey also asked respondents about a few other concepts associated with the afterlife or the supernatural.

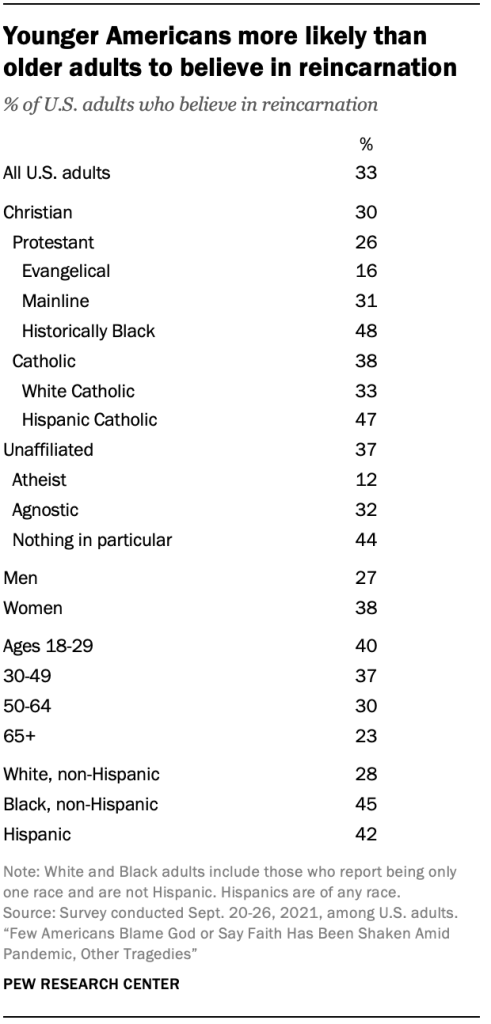

Though the share of adults who believe in reincarnation – i.e., that “people will be reborn again and again in this world” – is much lower than the share who believe in heaven or hell, it is a view held by a substantial minority of the population (33%).

Just as with heaven and hell, women are more likely than men to believe in reincarnation (38% vs. 27%), but the age pattern on this question differs from the ones observed on the prior two questions. Whereas younger Americans are less likely than their elders to believe in heaven and hell, younger adults are more likely to believe in reincarnation. Nearly four-in-ten adults under the age of 50 (38%) believe in reincarnation, compared with 27% of those ages 50 and older.

Overall, Catholics are more likely than Protestants to say that they believe in reincarnation (38% vs. 26%), but there is wide variance within these groups. Nearly half of Hispanic Catholics (47%) believe in reincarnation, compared with a third of White Catholics. The gap among Protestants is even more pronounced: 48% of members of the historically Black Protestant tradition say they believe in reincarnation, while just 31% of mainline Protestants and only 16% of evangelical Protestants say the same. Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, belief in reincarnation is on par with belief in heaven, with 37% of respondents in this group saying that they believe that people will be reborn again and again in this world – higher than the share of Protestants who hold this view.

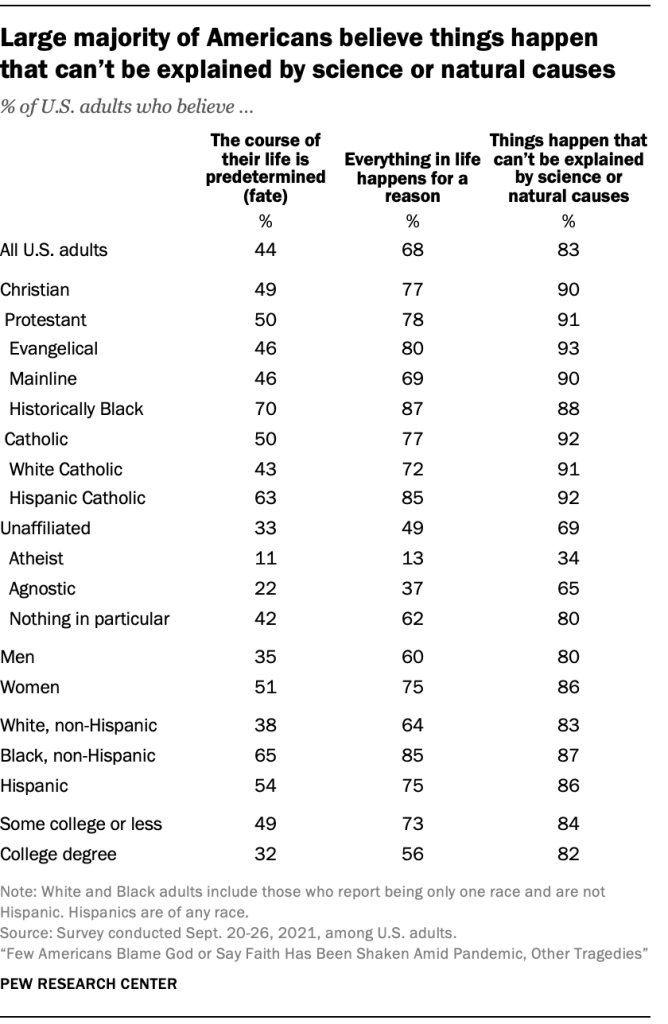

Overall, 44% of U.S. adults say they believe in fate, defined as the course of their life being predetermined. This group includes half of women (51%) and 35% of men. There also are differences based on levels of educational attainment, with college graduates significantly less likely than those without a degree to say they believe in fate (32% vs. 49%).

Protestants and Catholics overall are identical on this question, with 50% in each group saying they believe in fate. But there is again wide variation along racial and ethnic lines within each group: Protestants in the historically Black tradition (70%) are much more likely than evangelical or mainline Protestants to believe in fate (46% for both evangelical and mainline Protestants), as are Hispanic Catholics compared with White Catholics (63% vs. 43%). One-third of religiously unaffiliated adults believe in fate, with those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” much more likely than atheists and agnostics to hold this view.

Differences among religious “nones” are even bigger on a question about whether everything happens for a reason. Most of those whose religion is “nothing in particular” (62%) say that everything in life does happen for a reason, compared with just 13% of atheists and 37% of agnostics. Overall, 68% of U.S. adults hold this view, including 78% of Protestants and 77% of Catholics.

An even larger majority of Americans (83%) believe things happen that cannot be explained by science or natural causes. Atheists are again a notable exception, with only a third (34%) saying they believe things happen that cannot be explained by science or natural causes.

Most Americans believe people can communicate with God or other higher power

The survey also gave examples of various supernatural occurrences and asked respondents to say whether they think each is possible, and if so, whether they had ever personally experienced it.

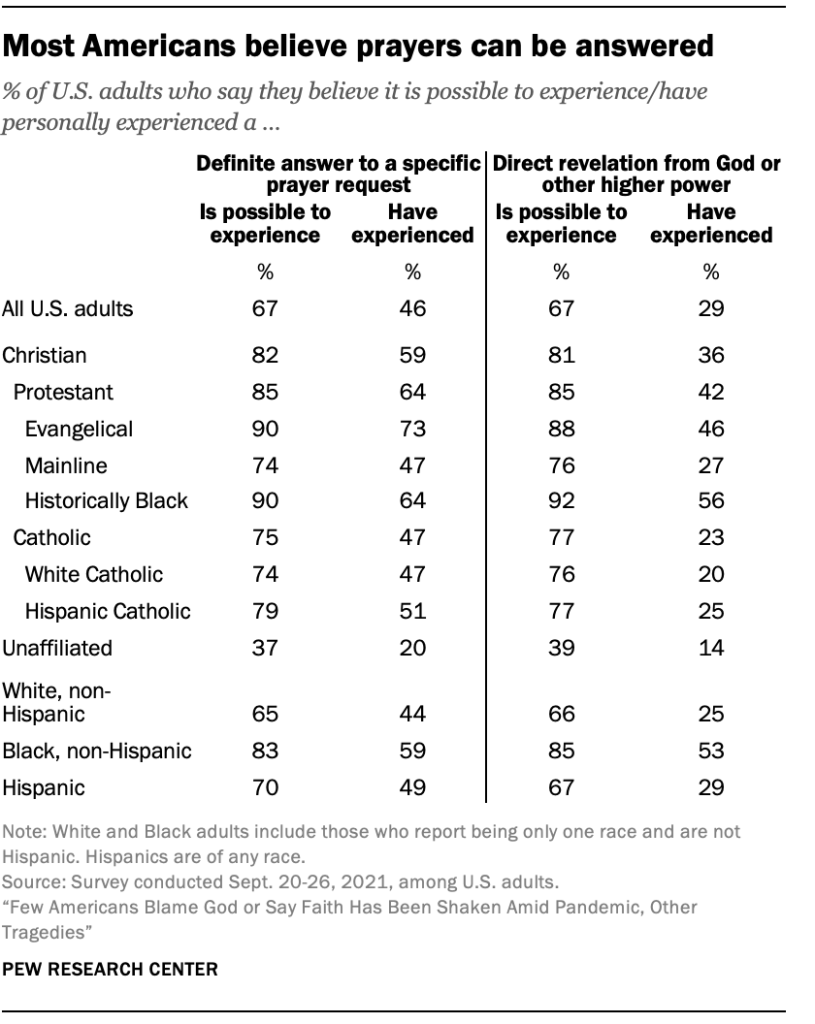

Fully two-thirds of U.S. adults believe it is possible for people to receive a “definite answer to a specific prayer request,” and the same share (67%) think it is possible to receive a “direct revelation” from God. Americans are more likely to say they have experienced the former (46%) than the latter (29%).

Overwhelming majorities of Protestants report believing both experiences are possible (85% on each question), and most even say that they personally have received a definite answer to a specific prayer request (64%). This experience is especially common among evangelical Protestants (73%), although members of the historically Black Protestant tradition are more likely than evangelicals to say they have experienced a direct revelation from God (56% vs. 46%).

Indeed, Black Americans are more likely than White and Hispanic Americans to say it is possible to have one’s prayers definitely answered and to receive a direct revelation from God or a higher power. Black Americans also are more likely to report having experienced these spiritual phenomena personally.

Most Catholics in the U.S. express belief that it is possible to receive a definite answer to a specific prayer request (75%) and a direct revelation from God (77%), though they are somewhat less likely than Protestants to say so. Fewer than half of religiously unaffiliated Americans say the same (37% and 39%, respectively).

Most believe some interaction is possible between the living and the dead

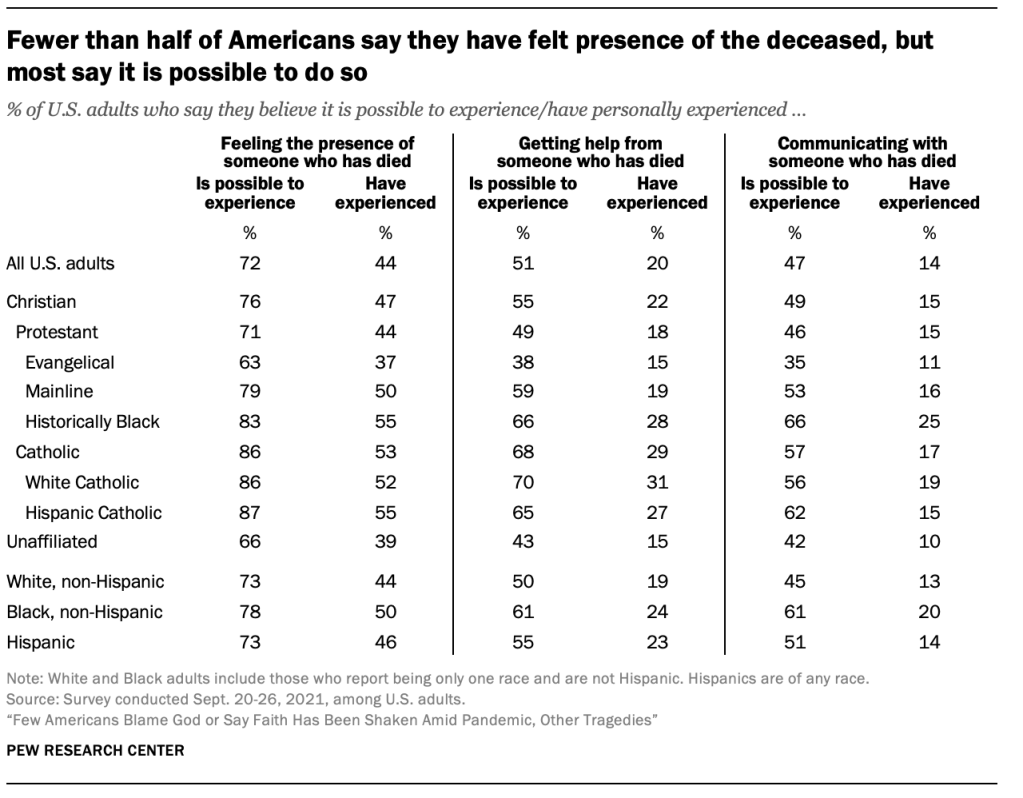

About seven-in-ten Americans say it is possible to feel “the presence of someone who has died,” while roughly half say that living people can be helped by those who have passed (51%) or communicate with them in some way (47%). When asked about their personal experiences with the deceased, 44% of U.S. adults say that they have felt the presence of someone who has died, while smaller shares say that they have received help from (20%) or communicated with (14%) someone who has died.

Contrary to the questions about interaction with God, Catholics are more inclined than Protestants to say it is possible for people to feel the presence of someone who has died (86% vs. 71%), with two-thirds of religious “nones” (66%) also expressing this view. Catholics also are most likely to believe it is possible to get help from the departed (68% vs. 49% of Protestants and 43% of “nones”) and communicate with them (57% vs. 46% and 42%, respectively). Evangelical Protestants, meanwhile, are no more likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to report believing in or experiencing all of these interactions with the deceased.

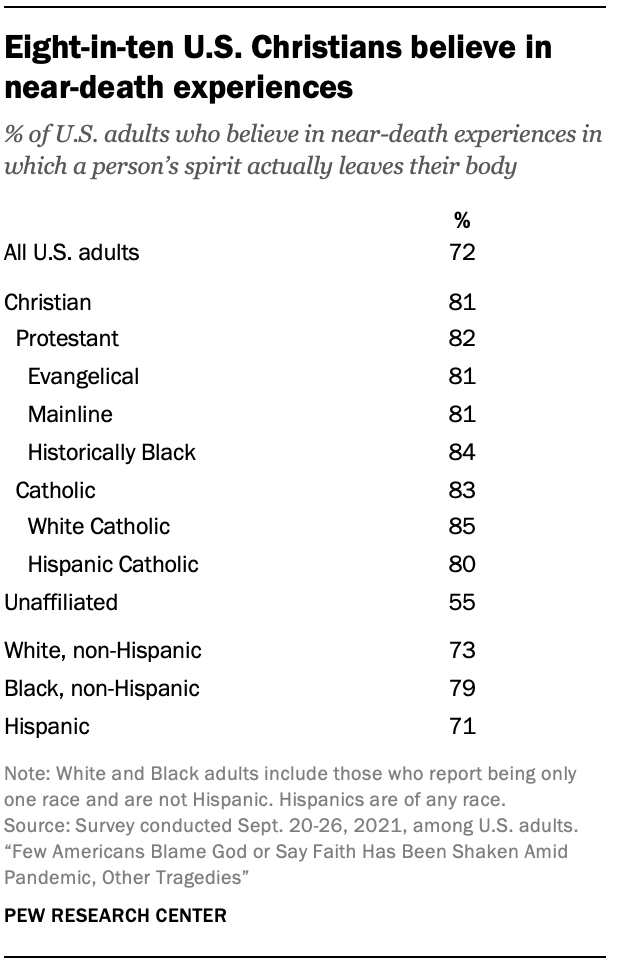

Almost three-quarters of all U.S. adults (72%) think it is possible for people to have “a near-death experience in which their spirit actually leaves their body.” Protestants (82%) and Catholics (83%) are more likely than the religiously unaffiliated (55%) to believe that such an experience is possible, as are Black Americans compared with Americans of other races.

The survey did not ask about whether people have actually had such an experience.