Confucianism

Named after the sage Confucius (b. 551 B.C.E.), Confucianism is one of the most important philosophical traditions in China. Although it’s widely considered a spiritual philosophy, some scholars classify it as a religion. Its beliefs center on a pervasive, invisible divine power – tian (天), usually translated as “heaven” – that controls humans’ fate and destiny. Confucian teachings focus on filial piety (xiao 孝), loyalty (zhong 忠) and benevolence (ren 仁).

Taoism (religious)

Founded by Zhang Daoling, religious Taoism (Daojiao 道教) dates to the second century C.E. The principal teachings of religious Taoism – similar to philosophical Taoism – focus on nonaction and harmony with the Tao, or universal order. Traditional practices include meditation; self-discipline in diet, exercise and sex; and rituals to promote harmony with the heavenly order or higher forces of the cosmos.

Chinese folk religions

Also called folk belief or minjian xinyang (民间信仰), Chinese folk religions were recorded as early as the Shang dynasty (c.1600-1046 B.C.E), well before Confucianism and Taoism. Folk religions originated in shamanism, and today include a broad range of beliefs and practices directed at supernatural forces — such as fortune telling and making wishes to ancestors and gods. Folk deities include the goddess of the sea (Mazu 妈祖) and the god of wealth (caishen 财神).

Relatively few Chinese adults formally identify with religious and philosophical traditions that originated in China – in large part because, unlike Abrahamic religions, these traditions do not emphasize membership. Moreover, Chinese people generally do not refer to these traditions as religion (zongjiao 宗教).

But Confucianism, Taoism and folk religions nevertheless have a role in the lives of many Chinese people. While a tiny share of Chinese adults describe themselves as believing in (xinyang 信仰) Taoism (Daojiao 道教), Confucianism (Rujiao 儒教 or Rujia sixiang 儒家思想) or folk religions (minjian xinyang 民间信仰), far more say they hold beliefs or engage in practices tied to these traditions.

And even though the Chinese government does not consider Confucianism to be a religion, some of its characteristics are within scholars’ conception of religion. For instance, the Confucian ritual of ancestor worship (jizu 祭祖) – an expression of filial piety (xiao 孝) toward deceased family members – often entails a belief in ancestral spirits and their supernatural power to intervene in earthly affairs.

Buddhism, which is considered a “traditional Chinese” religion even though it originated in India, has strong links to these other belief systems. (Read Chapter 3 on Buddhism.)

Confucianism, Taoism, folk religions and Buddhism are often deeply intertwined, and the differences among them can be indistinguishable to Chinese people. For example, Confucian teachings on ancestor veneration permeate China’s spiritual traditions, such as in the Buddhist Ullambana Festival (Yulanpen Jie 盂兰盆节) and Taoist Zhongyuan Festival (Zhongyuan Jie 中元节). Both events take place annually in Lunar July, a time when ghosts, including deceased ancestors, are believed to visit the world of the living. And both festivals incorporate filial piety (xiao), as manifested during a ritual in which ancestral spirits are commemorated and “rescued” from their suffering.

Folk beliefs and practices, meanwhile, incorporate Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist concepts and also turn them into distinctly folk religious elements. For instance, the popular folk deity, the goddess of mercy (Guanyin 观音), was originally the Buddhist figure Avalokiteśvara, a bodhisattva of compassion often depicted as genderless or male. In Chinese folk religion, Guanyin is understood as a goddess who answers all prayers, including requests for wealth, health, good fortune and giving birth to a son.

Historically, Confucianism, Taoism and folk religions – along with Buddhism – have helped shape Chinese people’s understanding of the universe. Even today, these traditions are tied to Chinese social norms and the country’s national holidays. Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which in the past were frequently referred to as the “Three Teachings,” typically garner more support from educated elites and authorities than do folk religions, which historically have been marginalized as “illegitimate” and “unorthodox.”15

Folk practices have their roots in shamanistic activities (wushu 巫术), which were recorded as early as the Shang dynasty (c.1600-1046 B.C.E.). Historical records indicate that Chinese elites engaged in fortune telling through diviners’ reading of oracle bones. Shamans (wu 巫), who at times held great prestige in royal courts, performed rituals such as rain-making ceremonies to break droughts.16

Confucianism emerged from the teachings of the philosopher Confucius, who was born in what is today Shandong province on China’s east coast in the sixth century B.C.E. His philosophy was captured by his disciples in “The Analects” (Lunyu 论语), published years after his death. “The Analects” is among Confucianism’s foundational texts, a collection that is known as the Four Books and Five Classics (Sishuwujing 四书五经).

There is a close link between Confucianism and shamanism. Scholars have argued that some Confucian concepts, including parts of the five constants (wuchang 五常), have their roots in shamanistic rituals.17 Confucianism became state ideology during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.) and took hold among Chinese elites. Shamanistic activities continued to be practiced by common people, morphing into the veneration of ancestors, heroes and local deities, and ultimately influenced some Buddhist and Taoist rituals, such as the Hungry Ghost Festival.18

Religious Taoism, influenced by a Taoist philosophy that dates back to the sixth century B.C.E., first emerged as a sect, founded by Zhang Daoling, during the second century C.E. But it was not until centuries later that aristocrats, reacting to the growing religion of Buddhism and seeking to preserve and defend Indigenous religious traditions, began identifying as “Taoist” and collecting Taoist texts.19 Religious Taoism’s principal teachings, similar to those of Taoist philosophy, focus on nonaction and harmony with the Tao, or universal order. Religious Taoism’s teachings also include internal alchemy (neidan 内丹), self-cultivation and spiritual refinement through meditation.

During the Southern and Northern dynasties (420-589), Taoism gained some credibility among the ruling classes as a legitimate guiding philosophy, and together with Buddhism and Confucianism came to be recognized as one of the “Three Teachings.” During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), emperors both regulated and promoted Taoist practices. Early Ming rulers controlled the number of ordained Taoists in the state and established temples throughout the kingdom for Taoist liturgies to be held in support of the state. They also occasionally invited Taoists to the royal court. Emperor Jiajing (1522-1566) – a devout Taoist known for his fascination with immortality, divination and alchemy – is one of Taoism’s best-known imperial adherents. Taoism fell out of favor with the ruling class during the Qing dynasty (1636–1911), when the emperors espoused Confucianism and Buddhism.

Starting in the late 19th century, intellectuals, political leaders and other elites – drawn initially to Western ideals of science and modernity, and later to Communist ideology – soured on traditional Chinese belief systems. This backlash came in waves and from different angles, producing a new vocabulary and framework to discuss and evaluate religious concepts.

During the late Qing period (roughly 1900-1911), Chinese scholars, influenced by Protestant ideals of religion, began to use the term zongjiao (宗教) to refer to organized religions, particularly those with professional clergy and institutional oversight. Around the same time, they adopted the new term mixin (迷信), meaning blind belief or superstition, to describe folk religions (minjian xinyang 民间信仰), and religious activities and beliefs outside zongjiao and Confucian orthodoxy. Some of this framework of separating zongjiao religion from other belief systems remains in place today.

In the 1920s, the government of the Republic of China launched a campaign against superstition, tearing down temples and shrines dedicated to folk deities.20 However, due partly to the fact that folk religious temples often housed deities of various religious traditions, local authorities did not fully implement the policy. Around the same time, during the New Culture Movement, intellectuals blamed traditional Confucian values for China’s political weakness and advocated for Western values, especially science and democracy.21

After the Communist Party took power, folk religions and Confucianism were attacked further during the socialist campaign in the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976. In 1982, the government accepted the legitimacy of zongjiao religion, but folk religions remained illegal. Authorities continued to denounce the “superstitious practices” of folk religions and strictly forbade sorcerers and witches, though folk activities that the government did not deem as harmful – such as fengshui (风水) and worshipping the goddess of sea, Mazu (妈祖) – were largely tolerated and sometimes encouraged.

Confucianism in particular serves as a morality template for many Chinese. In recent decades, there has been growing discussion in Chinese society about “moral decline,” and commentators sometimes blame gruesome or senseless crimes on China’s loss of a “moral compass.”

In 2015, the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) included a question about Confucianism and moral values: “Some people say the moral conditions in society are not ideal. If we were to restore moral values in society, what role do you think the Confucian tradition should play?” About two-thirds of respondents said efforts would need to rely at least partly on the Confucian tradition.

Authorities in China often differentiate between traditional beliefs and practices they consider to be “custom,” which are tolerated, versus those that are “superstition” and therefore discouraged or banned. (Some superstitious activities deemed to be “harmless” are allowed.) These distinctions may be blurry and subjective, but they are at least partly rooted in the history of Confucianism, Taoism and folk religion in China.

A Chinese family performs the ritual of ancestor worship during Lunar July, when the deceased are believed to visit the world of the living. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Festivals and traditions honoring ancestors

The Confucian practice of paying respects to deceased ancestors as if they were living is observed across religious traditions during the month of Lunar July, a time when tradition teaches that the gate of the underworld opens, and ghosts and spirits, including deceased ancestors, are allowed to visit the world of the living.

Folk religion: (Hungry) Ghost Festival (Gui Jie 鬼节)

People make offerings of food and “spirit money” to ghosts and ancestors.

Buddhism: Ullambana Festival (Yulanpen Jie 盂兰盆节)

A festival centered on filial piety and gratitude to all beings. Buddhist monks traditionally perform a ritual called “releasing the flaming mouth” to rescue ghosts, including ancestors, from their suffering.

Taoism: Zhongyuan Festival (Zhongyuan Jie 中元节)

The Taoist deity, Ruler of the Earth, is believed to pardon ghosts of their sins. Taoist priests perform Zhongyuan fasting and offering rituals to rescue ghosts, including ancestors, from their suffering.

Beliefs and practices

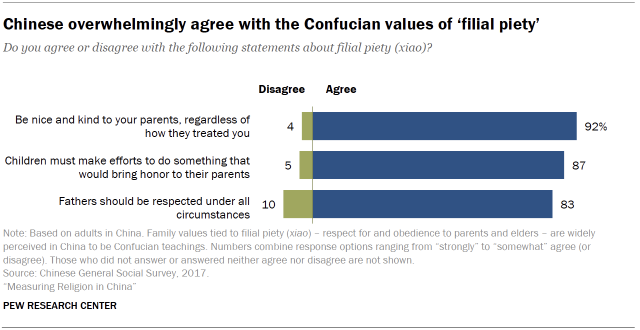

Beliefs and practices tied to Confucianism, Taoism and Chinese folk religions generally fall into three broad areas: filial piety (xiao 孝) and ancestor worship (jizu 祭祖), veneration of deities and ghosts, and beliefs that involve supernatural forces, such as fengshui (风水).22

While some of these concepts appear to be distinctly Confucian (ancestor worship), Taoist (belief in Taoist deities), folk religious (caring about auspicious days) or even Buddhist (belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva), they defy clear categorization. There is a lot of overlap among these traditions, and Confucianism, Taoism, folk religion (and Buddhism) all are considered to be part of traditional Chinese culture.

In addition, Chinese people often engage in religious beliefs and practices with a range of origins without distinction. Folk religion in particular blends elements from a variety of Chinese traditions, so separating folk beliefs and practices from more “orthodox” belief systems is particularly difficult.

Filial piety and ancestor worship

In its basic form, filial piety (xiao) refers to one’s duties and indebtedness to parents, even after their death. These duties include respect, obedience and care for parents and elderly family members.

In Confucian teachings, ancestor veneration – and the associated ancestral rite (jili 祭礼) described in Confucian texts – is an expression of filial piety. Confucianism’s tenet of filial piety is a pillar of social norms across East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia.

As described in “The Analects,” the ancestor veneration ceremony or rite involves fasting in preparation, wearing ceremonial costumes, and offering elaborate meals to deceased ancestors. One is expected to perform the rites carefully and pay respects to the deceased as if they were living. Confucius was said to insist that venerating ancestors is not a religious act but a form of fulfilling filial responsibilities. Still, the ceremony entails the belief that deceased ancestors continue to exist.

Other Chinese religious traditions have adapted the concept of ancestor veneration in their own way. In Chinese folk religion, for example, failure to venerate one’s ancestors properly brings divine punishment, and the spirits of the dead who were not venerated by their living descendants become “wandering ghosts.”

In China today, ancestor veneration rituals, such as those performed during gravesite visits, are typically steeped in folk religion. Gravesite visits often involve rituals with religious underpinnings, such as burning incense and “spirit money” or joss paper, making offerings of food and drink, and making wishes to ancestors.23

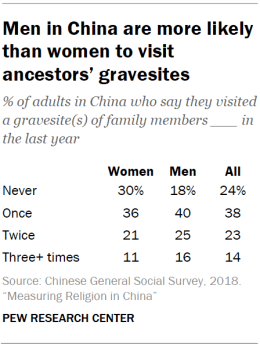

Three-quarters of Chinese adults report that they visited a family member’s gravesite at least once in the last year, according to the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS).

The survey did not ask what rituals people perform at gravesites. Some Chinese people may not engage in any activity that has spiritual or religious underpinnings while caring for an ancestor’s grave. But ethnographic research suggests that Chinese people typically burn incense and “spirit money” when visiting family members’ gravesites.

While most Chinese people venerate ancestors, very few do it as frequently as tradition dictates. Custom calls for paying respects to ancestors at a family gravesite three times a year: on Tomb Sweeping Day, during the Chinese New Year and on the anniversary of an ancestor’s death.

In 2018, only 14% of adults in China said they had visited a family member’s gravesite three times or more in the past year.

Many Chinese people oppose cremations because they are viewed as violating the Confucian understanding of respect for the dead.24 Since 1956, the Chinese government, citing the amount of arable land devoted to burials, has promoted cremation, but the cremation rate has remained far below the government’s target.

Deity worship

In Chinese religious tradition, supernatural beings typically include gods – or deities – and ghosts, i.e., the spirits of the dead. While the spirits of deceased ancestors fall into the category of “ghosts”(gui 鬼), Chinese people rarely use this term to describe their own deceased ancestors.

Gods, which are usually viewed as benevolent and having the power to intervene in worldly affairs, are believed to reside in heaven, Earth or the underworld. They follow a divine hierarchical structure and oversee a jurisdiction in accordance with their position. They may include Buddhist figures, Taoist immortals (shenxian 神仙) and local deities outside of the Buddhist or Taoist pantheons.

Gods can also be the spirits of human heroes. For instance, Lord Guan (Guan Gong 关公) was originally a renowned military general, Guan Yu (160-220 C.E.). He was worshipped by ordinary people as the god of war after his death, and later also by Confucian elites, who extolled Guan Yu as a moral exemplar of loyalty and honesty. Guan Yu was also granted the Buddhist rank of bodhisattva during the Sui dynasty (581-618), and the Taoist title of Emperor Guanduring the reign of Song Emperor Huizong in the 12th century.

Ghosts are often believed to possess the power to intervene in worldly affairs, but they can be malevolent and are of a lower rank than gods. Ghosts are usually confined to the underworld, except during the month of Lunar July, also known as “Ghost Month,” when the gate of the underworld opens and ghosts are allowed to visit the world of the living. It is believed that making food offerings and burning “spirit money” can appease ghosts and prevent them from harming the living.

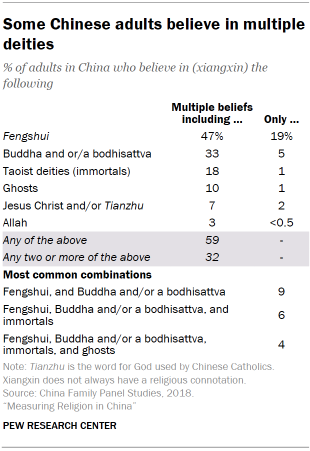

Belief in deities, including Buddha and/or a bodhisattva and immortals, is more common than belief in ghosts. For example, 18% of Chinese adults express belief in immortals, compared with 10% of adults who believe in ghosts, according to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS).

Because some gods are venerated across religious traditions, it is not always clear which religion(s) such practices fall into. For instance, burning incense to pay respects to Buddha (shaoxiangbaifo 烧香拜佛) may appear to be a Buddhist practice, but this activity is found across Chinese religious traditions.25 Some people may burn incense to pay respects to Buddha while incorporating distinctly folk religion practices, such as simultaneously making wishes to Buddha.26 Likewise, it is unclear whether a person who says they believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva should be considered a Buddhist or a practitioner of folk religion.

Burning incense (shaoxiang 烧香) – usually incense sticks – is believed to open up communication with gods so they can more readily hear people’s wishes. It is an essential component of venerating or paying respects to deities and ancestors, and in Chinese folk religious traditions, burning incense is typically accompanied by making wishes (xuyuan 许愿). Today, the term shaoxiangbaifo is commonly used to describe the act of venerating one or more deities of traditional Chinese religions.

Roughly a quarter of Chinese adults (26%) say they burn incense – at home or in temples – to pay respect to Buddha or deities a few times a year or more, including 11% who do so at least once a month, according to the 2016 CFPS.27 And 24% say they visited a particular destination – typically a temple or shrine – to pray for good fortune in school, business or other matters in the past year, according to the 2018 CGSS.

These measures suggest that most Chinese people are not frequently engaged in traditional religious activities. However, this low level of engagement is consistent with Chinese religious tradition, where people are not expected to pay respects to a god or gods regularly.

Rather, as some scholars have argued, religious engagement in China largely revolves around efficacy (ling 灵or lingyan 灵验) – how well a particular god or ritual responds to a person’s request – and believers are “consumers” who choose from the full array of gods and religious rituals when the need arises.28

Supernatural forces

In Chinese religious tradition, apart from gods and ghosts, supernatural forces, such as fate (ming 命), fortune (yun 运) and fengshui may affect or even largely shape one’s life.29 While ming is predestined and immutable, yun changes. There are a variety of divination practices believed to bring good fortune or ward off bad luck, such as fengshui maneuvering – the practice of arranging objects to create harmony between individuals and their environment – wearing lucky charms, and selecting auspicious days for special occasions.30

Chinese people commonly describe these practices as custom or superstition (mixin 迷信), though they are known to have Taoist underpinnings. It is not always clear whether the practice should be considered religious or which religious tradition it falls under. For instance, some people may consider their fengshui practice to be scientific, while others may hire Taoist priests to perform fengshui activities in a folk religious way, and still others may practice it in a purely Taoist way, as part of Taoist health rituals.

Approximately six-in-ten adults (62%) say they care “somewhat” or “very much” about choosing an auspicious day for special occasions, according to the 2018 CGSS. Almost half (47%) believe in fengshui, according to the 2018 CFPS. And 8% of Chinese adults say they carry a lucky charm or amulet to bring good fortune or keep them safe from harm.

Mixing of beliefs and practices

Traditional Chinese religious or spiritual beliefs and practices are not mutually exclusive. Beliefs in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals and fengshui overlap considerably, and few Chinese hold only one belief. For example, just 5% of adults say they believe in (xiangxin 相信) Buddha exclusively, compared with 9% of adults who say they believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva and fengshui at the same time. An additional 6% also believe in Taoist immortals.

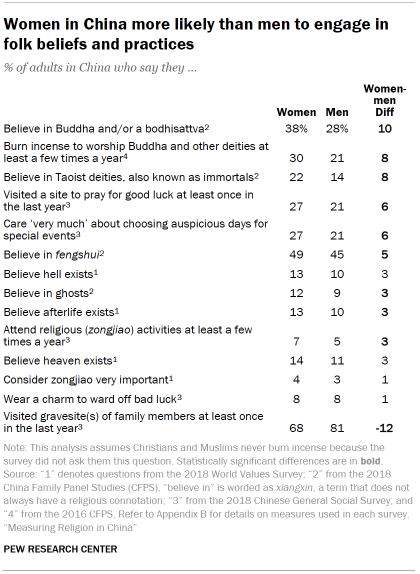

There are significant differences on these belief and practice measures across demographic groups. On average, women, older adults and people with less educational attainment tend to be more engaged in folk religion.

For example, women are consistently more likely than men to say they burn incense to venerate Buddha or other deities. They are also more likely to believe in folk deities, fengshui and auspicious days. However, women are less likely to visit the gravesite(s) of family members, as men are primarily responsible for performing that ritual, according to custom.

Affiliation

The share of Chinese adults who describe their religion (zongjiao) as Confucianism, Taoism or folk religion is much smaller than the share who engage with beliefs and practices from these traditions.

The most common of these identities is folk religion, but still, only about 3% of adults in China identify as adherents of folk religions, according to the 2018 CGSS.31

The CGSS is the only national survey that includes “folk religion” in the religious affiliation question, and it presents worshipping Mazu (妈祖), the goddess of sea, or Guan Gong (关公), commonly venerated as the god of wealth, as examples of folk religion.

The CGSS question may not capture some adults who worship other folk deities, such as the goddess of mercy (Guanyin 观音), earth gods (tudigong 土地公), dragon king (longwang 龙王) or Silkworm Mother (Cangu Nainai 蚕姑奶奶).

Some Chinese people who engage in deity worshipping may not consider themselves religious in the formal sense because folk religion is commonly regarded as superstition in China, which the government discourages.

In addition, scholars have noted that practitioners of folk religion sometimes refer to all forms of folk religion as Buddhism and claim Buddhist affiliation, even though they mostly practice folk religion. (Read Chapter 3 for details on Buddhism in China).32

Many people in China do not consider Confucianism to be a religion. This report does not analyze Confucianism as a religious affiliation, and we do not make any estimate of the number of Confucians in China. Taoism is one of the five religions recognized by the government (along with Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam and Protestantism), but very few Chinese adults identify as Taoists in the 2018 CGSS.33

Sidebar: How many Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian and folk religious sites are there in China today?

For various reasons, it is unclear exactly how many traditional Chinese worship sites (temples and shrines with Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian or folk religious elements) there are across China today. Nor is it clear which sites are most common. This sidebar describes the government’s official statistics as well as some unofficial estimates based on surveys of “neighborhood committees,” explaining why neither set of numbers is wholly reliable.

Official data

Chinese government statistics show a total of 43,000 temples – about 34,000 Buddhist sites and 9,000 Taoist sites – across the country as of 2018. However, this count covers only officially registered Buddhist and Taoist venues, which typically include a monastery or housing for monks or nuns, as well as a prayer hall that is open to the public for worship.

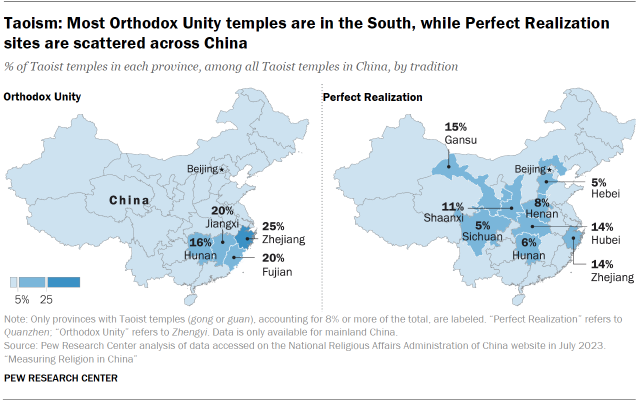

Buddhist temples (si 寺 or siyuan 寺院) included in the official statistics are categorized based on their school: Han, Tibetan or Theravada. (Refer to the Buddhism chapter for more details.) Taoist temples (gong 宫 or guan 观) are usually classified as belonging either to the Perfect Realization tradition (Quanzhen 全真) or to the Orthodox Unity tradition (Zhengyi 正一).34 According to the official figures, somewhat more Taoist temples belong to Orthodox Unity (4,338) than to Perfect Realization (4,011).35 Also, the Perfect Realization tradition has a stronger presence in northern China, while Orthodox Unity tends be more widespread in southern regions, according to data from the National Religious Affairs Administration of China.

Buddhist or Taoist sites without formal registration are excluded from the official statistics. It is possible that the number of unregistered Buddhist and Taoist sites far exceeds those registered, given the high bar for registration, such as having steady income and qualified clergy. In addition, the managers of many sites may have little incentive to register, because local authorities often permit unregistered Buddhist or Taoist venues to operate without much difficulty.36

Meanwhile, folk religion sites – which are mostly shrines and temples– are not tracked closely by the government since folk religion is not one of China’s five official religions and does not have its own supervisory agency.

In 2015, the Chinese government issued, for the first time, a national document urging local governments to regulate folk religion and its sites. However, registration requirements for folk religion sites vary widely by province. For instance, in Guangdong province, any folk religion site seeking to register must have a minimum building area of 500 square meters (5,382 square feet), while in Hunan province, the requirement is just 50 square meters. These inconsistencies add to the challenge of estimating the number of folk religious sites across China.

Although Confucianism is not officially recognized by the government as a religion, there is a national association that tracks Confucian temples (wenmiao 文庙 or kongmiao 孔庙). Traditionally, these were sacred places reserved for educated elites to worship Confucius. Today, they are open to all visitors. Government statistics show 1,600 Confucian temples across China. However, this count does not include ancestral halls or temples (zongci 宗祠 or citang 祠堂) – places of worship dedicated to ancestors of the same family lineage, which are closely tied to Confucianism.

Estimating numbers of worship sites from surveys of local jurisdictions

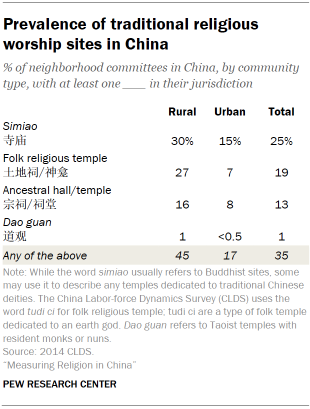

Survey data provides an alternative way to estimate the prevalence of traditional religious sites. The 2014 China Labor-force Dynamics Survey (CLDS) of neighborhood committees – the smallest administrative unit in China – indicates that 35% of such committees have in their jurisdiction at least one temple or shrine associated with traditional Chinese religions, such as a temple with a Buddhist connection (simiao 寺庙), a Taoist temple that includes a monastery (dao guan 道观), an ancestral hall (zongci or citang), or a folk temple dedicated to an earth god (tudi ci 土地祠) or shrine dedicated to other local deities (shenkan 神龛).

All told, the CLDS data suggests there may have been as many as 280,000 traditional worship sites in China in 2014.37 However, that figure also may be low. Although the survey asked about the presence of temples without specifying their registration status, it is possible that neighborhood committees reported only temples that had received some type of government approval, such as formal registration or at least tacit consent from local officials.

Ancestral halls

The CLDS report on neighborhood committees shows that about 13% of such committees have in their jurisdiction at least one ancestral hall (zongci or citang). Neighborhood committees in rural areas, known as “villagers’ committees,” are particularly likely to have at least one site dedicated to ancestors (16%). A neighborhood committee generally represents between 1,000 and 3,000 households, while a villagers’ committee is comprised of an average of around 370 households.38

These numbers suggest there are more than 102,000 ancestral halls in China. But this may be a conservative estimate, because 7% of neighborhood committees report having two or more ancestral temples in the survey.

Buddhism

CLDS data indicates there were more than 190,000 Buddhist temples (simiao) in China, far greater than the government’s count of 34,000 officially registered Buddhist sites. However, that 190,000 figure could overstate the number of Buddhist venues with a monastery, because the term “simiao”is also sometimes used to describe any temple or shrine that houses Buddhist deities along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

Taoism

As for Taoist temples, CLDS data indicates that only 1% of neighborhood committees have at least one such temple in their jurisdiction. However, this count is based on a survey question asking about dao guan, which are temples with resident Taoist monks or nuns. It does not account for worship sites with some looser Taoist connection, such as temples or shrines that house Taoist deities along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

Folk religion

Folk religious temples, measured by the presence of temples (tudi ci) or local shrines (shenkan), seem to be relatively common in China, being present in 19% of neighborhood committees, according to the 2014 CLDS. Neighborhood committees in rural areas are particularly likely to have a site dedicated to local folk deities (27%). However, not all folk religious sites are dedicated solely to local folk deities, national heroes, trade gods, and/or other so-called “tutelage” or protector gods (such as the mountain god). In fact, it is common for folk religious temples also to house Buddhist or Taoist figures.

As a result, the CLDS-based estimate that there are at least 165,000 folk temples (tudi ci) or local shrines (shenkan) might not count some sites that house Buddhist or Taoist deities together with folk deities, thus leading to a possible undercount of folk religious sites in China.

Furthermore, while the CLDS data may seem to suggest that Buddhist temples are the most common variety in China, this conclusion may not be warranted, due to the complex interconnections of Buddhism, Taoism and folk religion. Some temples or shrines may not fall neatly under one religious category, because they house multiple Buddhist, Taoist and folk deities at the same time.

There is some evidence suggesting the number of temples that fall outside of official statistics declined in the past decade when local authorities tightened controls over folk religion. For example, in Zhejiang, 35,000 folk religious sites were listed in 2013, but that number dropped by half to 17,000 in 2020 as sites that failed to meet the government’s registration requirement were demolished, closed or converted into secular facilities.