When it comes to evaluating scientists associated with food and healthy eating, Americans tend to hold more positive views of practitioners (namely, dietitians) than nutrition research scientists. At least half or more of the public trusts dietitians to perform their job well, to provide fair and accurate information and to care about their patients’ interests all or most of the time. Nutrition researchers stand out among the six specialties for low marks among the public when it comes to competence, trustworthiness of information and concern for public interest.

Americans tend to be skeptical of both groups when it comes to whether they can be counted on for transparency and taking responsibility for their mistakes. Most people also do not believe these scientists are likely to routinely face serious consequences for misconduct.

Familiarity with these groups makes a difference, however. People who are more familiar with the jobs of dietitians or nutrition researchers tend to hold more positive and trusting views of these groups. Those with higher levels of factual science knowledge, too, are more positive and trusting of scientists working in these areas.

Dietitians and nutrition research scientists

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports approximately 64,670 dietitians and nutritionists were employed in the U.S. as of May 2018. Dietitians commonly must register with a state regulatory body in order to practice. Several terms may be used for nutrition research scientists. The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines “food scientists and technologists” as those who “use chemistry, biology, and other sciences to study the basic elements of food. They analyze the nutritional content of food, discover new food sources, and research ways to make processed foods safe and healthy ….” In May 2017, approximately 15,020 food scientists and technologists were employed in the U.S.

The Center’s survey asked respondents about either dietitians or nutrition research scientists. Respondents were given brief definitions prior to answering questions about each group. These were:

“Dietitians advise people on what to eat using their training in nutrition in order to promote health and manage disease.”

“Nutrition research scientists conduct research about the effects of food on health.”

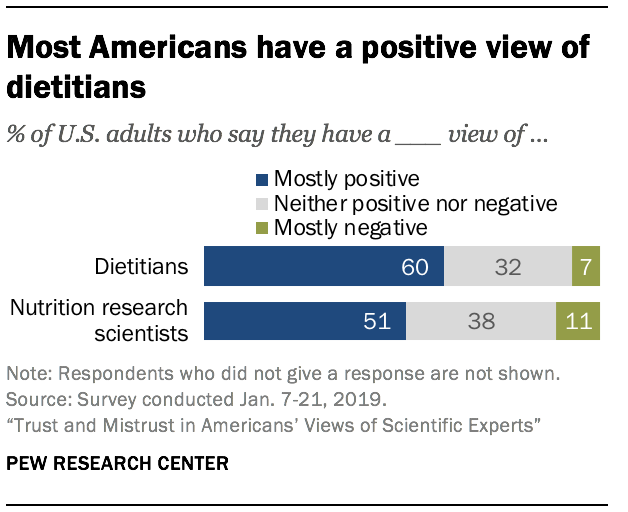

Overall, six-in-ten Americans (60%) say they have a positive view of dietitians. Another 32% say they have a neither positive nor negative view, while just 7% have a negative view of this group.

By comparison, Americans are somewhat less positive about nutrition research scientists. Half of the public (51%) holds an overall favorable view of nutrition research scientists, while 38% are neither positive nor negative, and 11% have a negative view.

Most Americans say that they know at least a little about the roles of dietitians (89%) or nutrition research scientists (74%).

Majorities of Americans say they have been exposed to these jobs through the news media. Roughly six-in-ten say they know about nutrition research scientists or dietitians because they have heard or read about their work in the news (59% and 57%, respectively). About four-in-ten (41%) say they know someone who is a dietitian, while just 16% claim to know a nutrition research scientist.

More trust dietitians than nutrition researchers when it comes to competence, commitment to people’s interests, trustworthiness of information

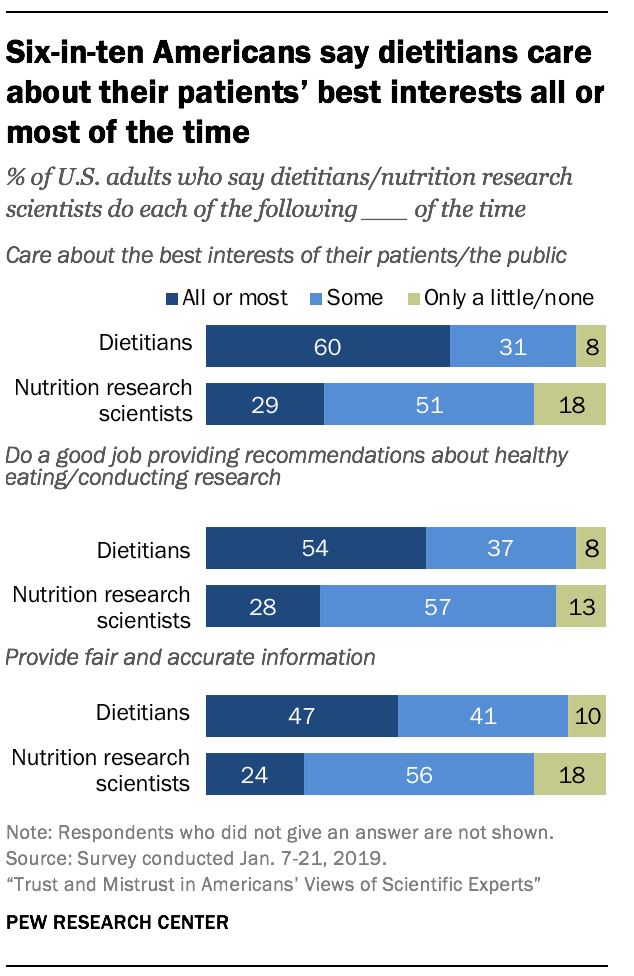

More than half of U.S. adults say dietitians care about the best interests of their patients (60%) or do a good job providing recommendations about healthy eating (54%) all or most of the time. About half (47%) also say dietitians provide fair and accurate information when giving treatment recommendations with the same frequency.

By contrast, about three-in-ten Americans say nutrition research scientists care about the best interests of the public (29%) or do a good job conducting research all or most of the time (28%). And about a quarter (24%) believe nutrition research scientists provide fair and accurate information about their research as often.

Greater familiarity with work of dietitians and nutrition research scientists correlates with higher confidence in their competence, accuracy of information

People who are more familiar with dietitians or nutrition research scientists tend to express more favorable opinions of these groups and their conduct.

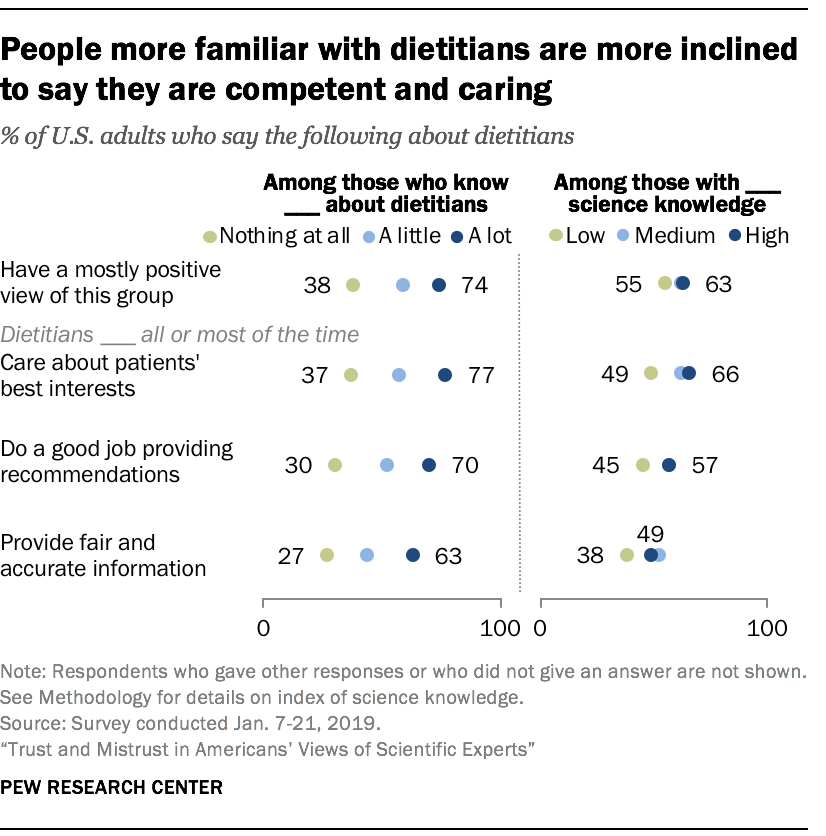

About three-quarters (74%) of Americans who know a lot about dietitians’ jobs report a mostly positive view of this group, compared with 59% of those who know a little and 38% of those who know nothing at all.

Familiarity with these jobs is also connected with a tendency to judge these researchers and practitioners as competent and accurate nutrition information sources.

Roughly three-quarters (77%) of Americans who know a lot about dietitians say they care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, compared with 37% of those who know nothing at all about dietitians − a difference of 40 percentage points. And 70% of those most familiar with this group say dietitians do a good job providing recommendations about healthy eating all or most of the time, while just 30% of those who are unfamiliar with dietitians say the same.

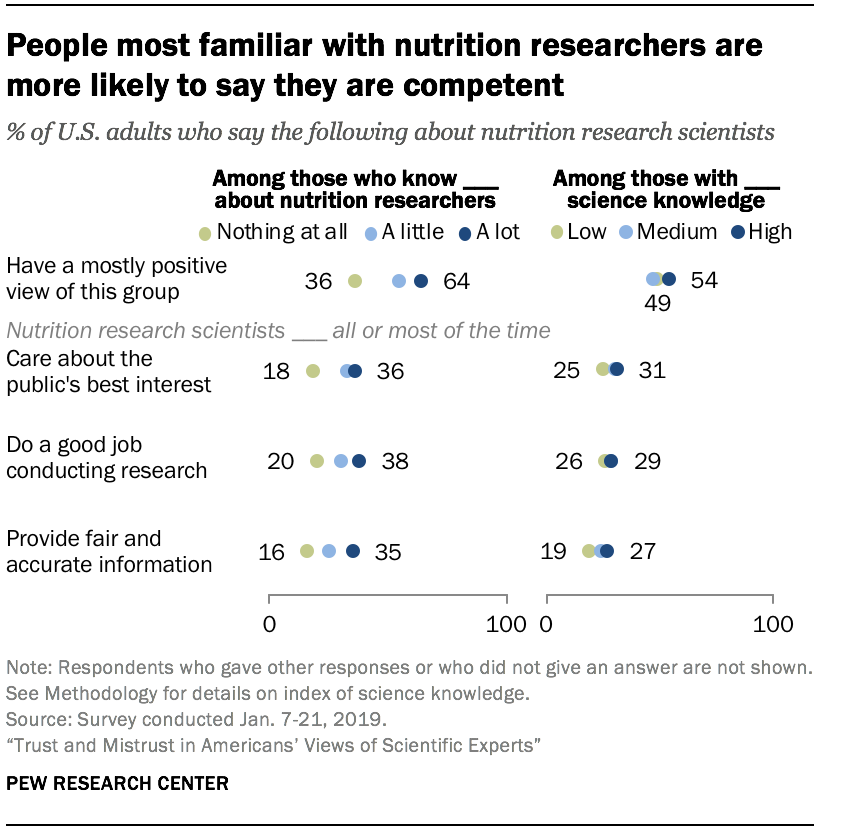

People’s level of familiarity with nutrition research scientists also tends to correlate with their views. Roughly two-thirds of those who are most familiar with nutrition research scientists (64%) say they have a mostly positive view of the group, while 36% of those who are unfamiliar hold the same view. In addition, 38% of those who know a lot about nutrition research scientists say they care about the best interests of the public all or most of the time, compared with 20% of those who are unfamiliar with this profession.

Americans with high levels of factual science knowledge judge dietitians somewhat more positively than those with low science knowledge when it comes to three key facets of trust. Two-thirds (66%) of those with high science knowledge say dietitians care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, while about half of those with low science knowledge (49%) say the same. And 57% of those with high science knowledge think dietitians do a good job all or most of the time, compared with 45% of those with low science knowledge. Similarly, 49% of those with high science knowledge say dietitians regularly provide fair and accurate information when making treatment recommendations, compared with 38% of those with low science knowledge. People’s level of science knowledge, however, is not similarly linked to their views about nutrition research scientists on these matters.

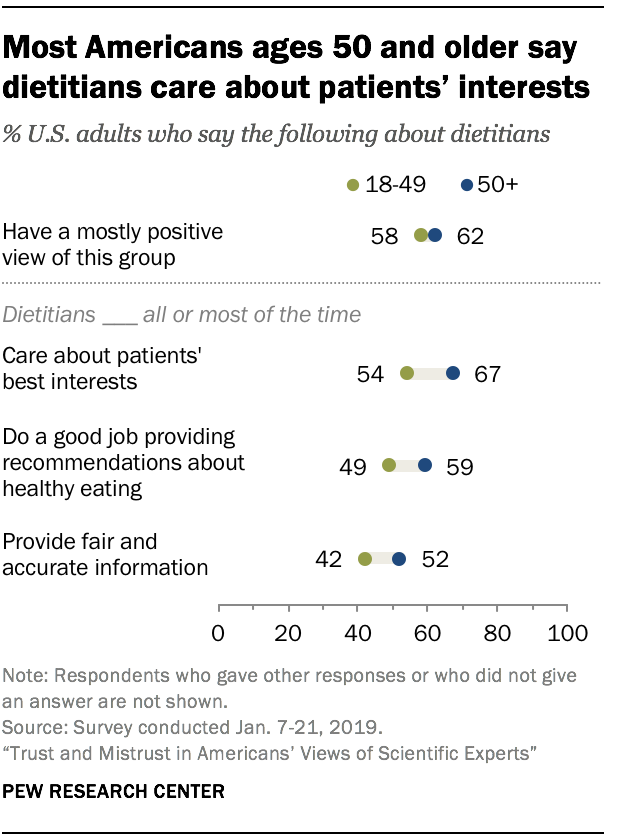

Americans ages 50 and older tend to have more positive views of dietitians than younger adults

Age and gender tend to correlate with views of dietitians.

Americans ages 50 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to say dietitians are competent, caring or a fair and accurate information source all or most of the time. For example, 67% of adults ages 50 and older say dietitians care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, compared with 54% of those under 50 who say the same.

There are also modest differences by gender in judgments of dietitians, with women somewhat more likely to express a positive overall view of dietitians (63% compared with 57% of men). Almost two-thirds of women (64%) see dietitians as caring about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, while 55% of men say the same. And 60% of women, compared with 47% of men, say dietitians do a good job providing healthy eating recommendations with the same frequency.

There are no differences by gender and modest differences by age (ranging from 3 to 6 percentage points) on these judgments of nutrition research scientists.

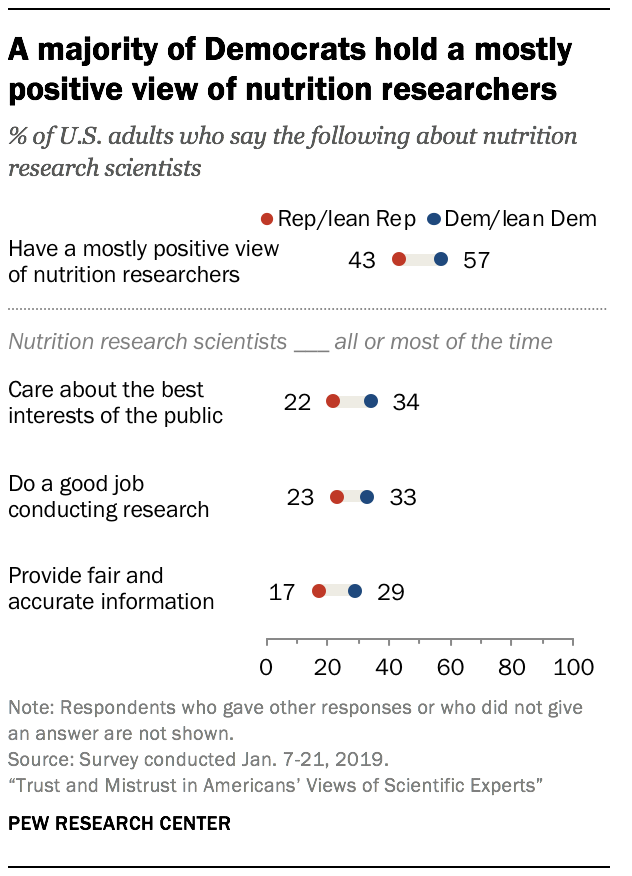

There are also some differences in views by political party for nutrition researchers, but not dietitians. A majority of Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party (57%) say they have an overall positive view of nutrition research scientists, compared with 43% of Republicans (including leaners).

Further, Democrats tend to have more confidence than Republicans when it comes nutrition researchers’ competence, concern for the public interest and accuracy of information. For example, 34% of Democrats say nutrition research scientists care about the best interests of the public all or most of the time, compared with 22% of Republicans.

There are no such partisan differences in views of dietitians.

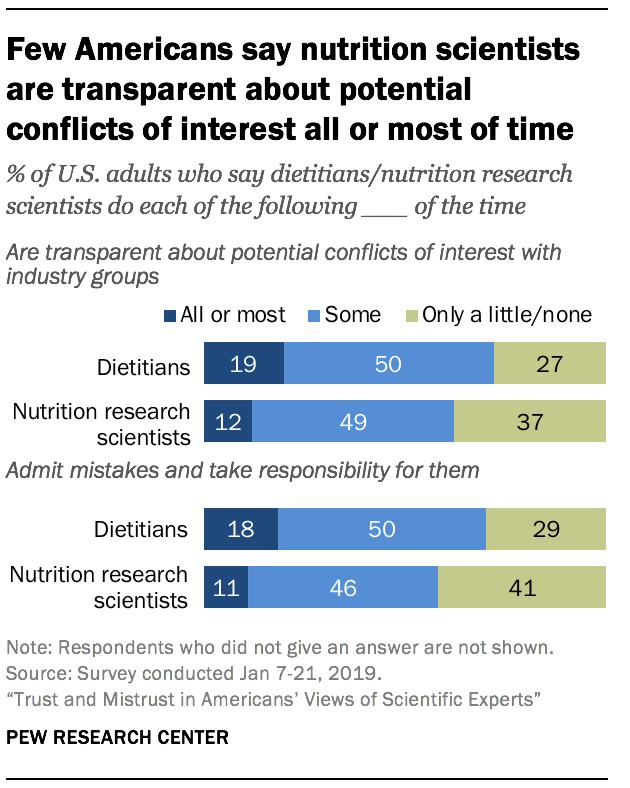

Few Americans believe nutrition professionals regularly admit mistakes or are open about potential conflicts of interest with industry

Americans are skeptical about whether nutrition research scientists and dietitians are transparent about potential conflicts of interest or take responsibility for their mistakes. At the same time, less than half of the public thinks misconduct is a big problem among each of these groups.

A minority of 19% say dietitians are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups all or most of the time; a similar share (18%) say they admit and take responsibility for their mistakes with the same frequency.

Just 12% say nutrition research scientists are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups all or most of the time; 11% say they take responsibility for their mistakes with the same frequency.

On the flip side, some 37% say nutrition researchers are transparent about potential conflicts of interest only a little or none of the time. And 41% say the same when it comes to nutrition researchers admitting and taking responsibility for their mistakes.

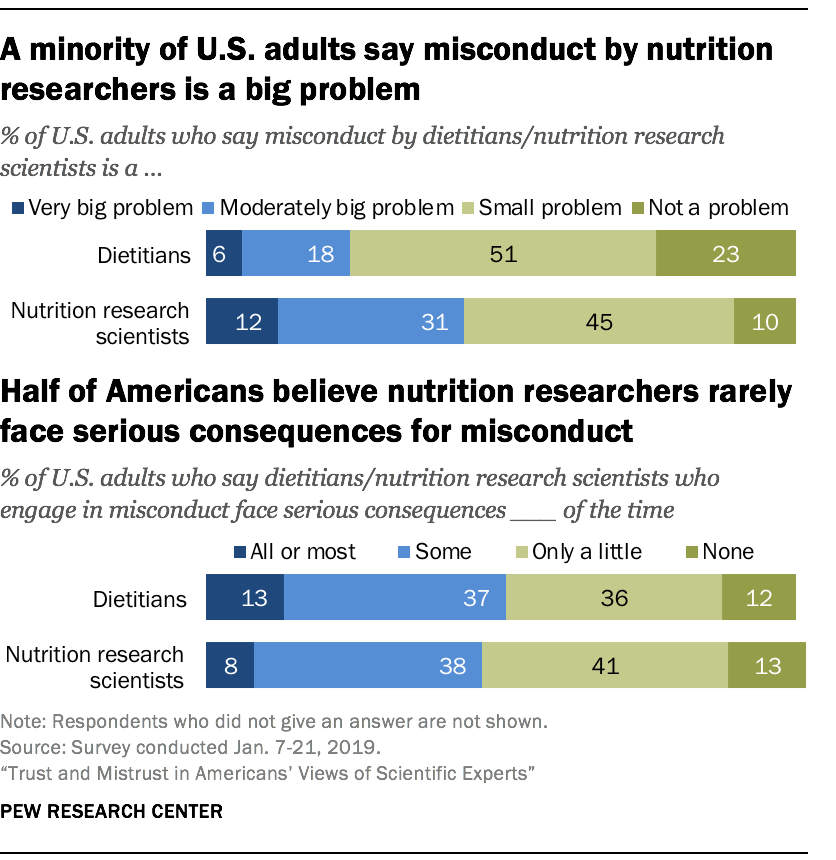

Most say misconduct is not a big problem among dietitians or nutrition researchers; about half say repercussions are infrequent

The survey asked Americans to consider the magnitude of the problem of research misconduct among nutrition research scientists or professional misconduct among dietitians. On that score, fewer than half consider misconduct to be at least a moderately big problem. About two-in-ten Americans (23%) say misconduct by dietitians is a very or moderately big problem. About twice as many (43%) say misconduct is at least a moderately big problem for nutrition research scientists.

Few Americans believe those who work in nutrition science regularly face serious consequences for misdeeds when they occur. Small shares of the public – 13% for dietitians and 8% for nutrition research scientists – say these groups face serious consequences for misconduct all or most of the time. Roughly half of the public says nutrition research scientists (53%) and dietitians (47%) face consequences only a little or none of the time.

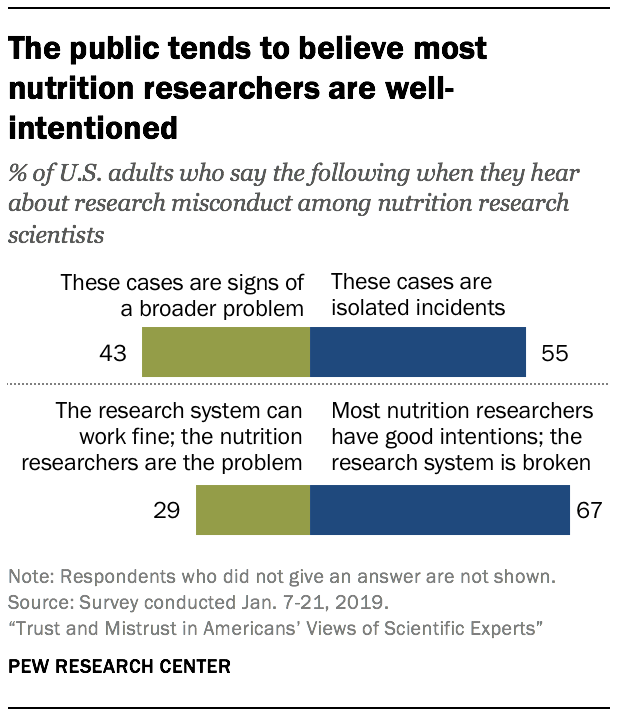

At the same time, Americans are inclined to give nutrition scientists the benefit of the doubt. A 55% majority say they consider misconduct cases to be isolated incidents, while 43% view such cases as signs of a broader problem. About two-thirds of the public (67%) say they generally believe that in cases of misconduct “most nutrition research scientists have good intentions; it’s the research system that’s broken.” A smaller share (29%) says, “The research system can work fine; it’s the nutrition research scientists that are the problem.”

For the most part, Americans tend to see dietitians’ role in professional misconduct similarly. Three-quarters of the public (75%) considers these misconduct cases as isolated incidents, while 22% view them as signs of a broader problem. And when it comes to identifying the source of the misconduct, 72% fall on the side of the dietitians, saying most have good intentions and it’s the system that is broken.

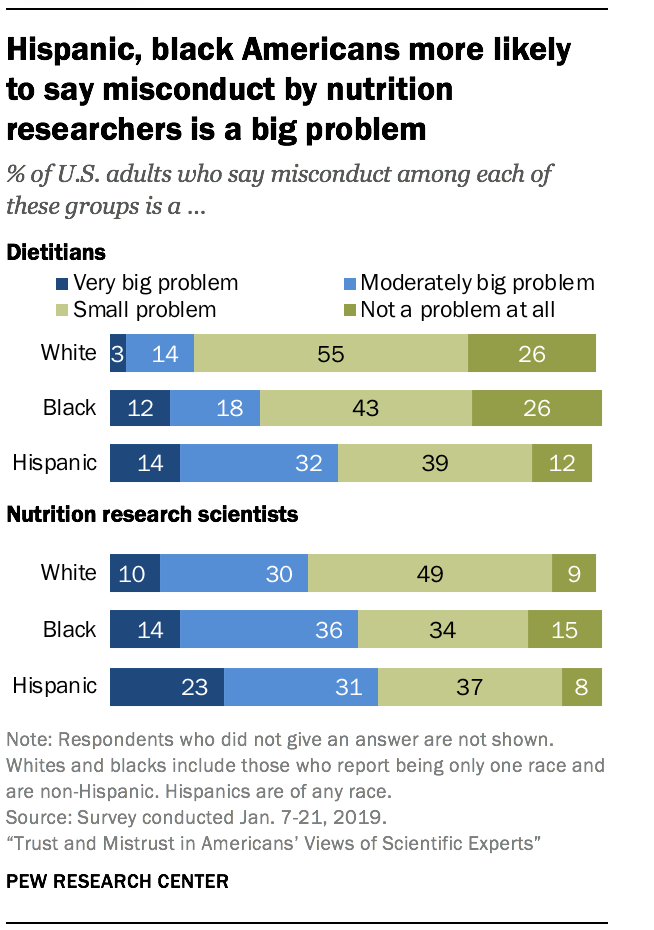

Concerns about the prevalence of misconduct are stronger among blacks and Hispanics than among whites. Slightly less than half of Hispanics (46%) say professional misconduct among dietitians is at least a moderately big problem; three-in-ten blacks (30%) say the same. In contrast, 16% of whites say misconduct is a big problem.

There is a similar pattern in beliefs about the prevalence of misconduct by nutrition research scientists. About half of Hispanics (54%) and blacks (50%) view misconduct by these scientists as at least a moderately big problem, compared with 40% of whites.