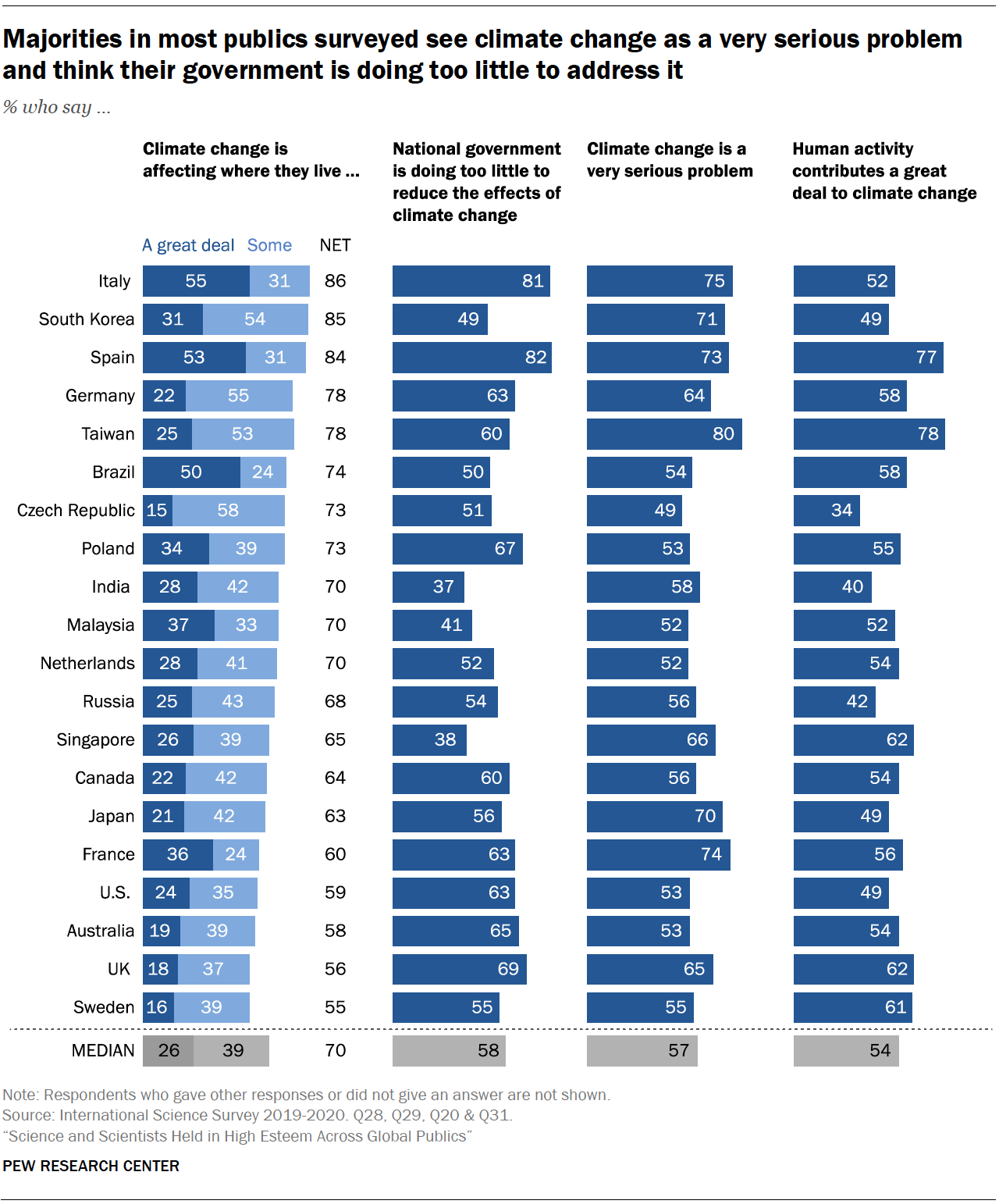

There is a common concern across most of the surveyed publics around environmental protection. A median of seven-in-ten report that climate change is having at least some effect in the area where they live. About half or more consider climate change to be a very serious problem; public concern about climate change is up since 2015 in places where a previous Pew Research Center survey is available. And, while there is some variation, majorities across most of these publics believe their national government is doing too little to address climate change.

When respondents were asked to choose between protecting the environment and job creation, the balance of opinion landed squarely on the side of environmental protection. (This survey was conducted before the coronavirus pandemic and resultant economic strains in many of these publics.)

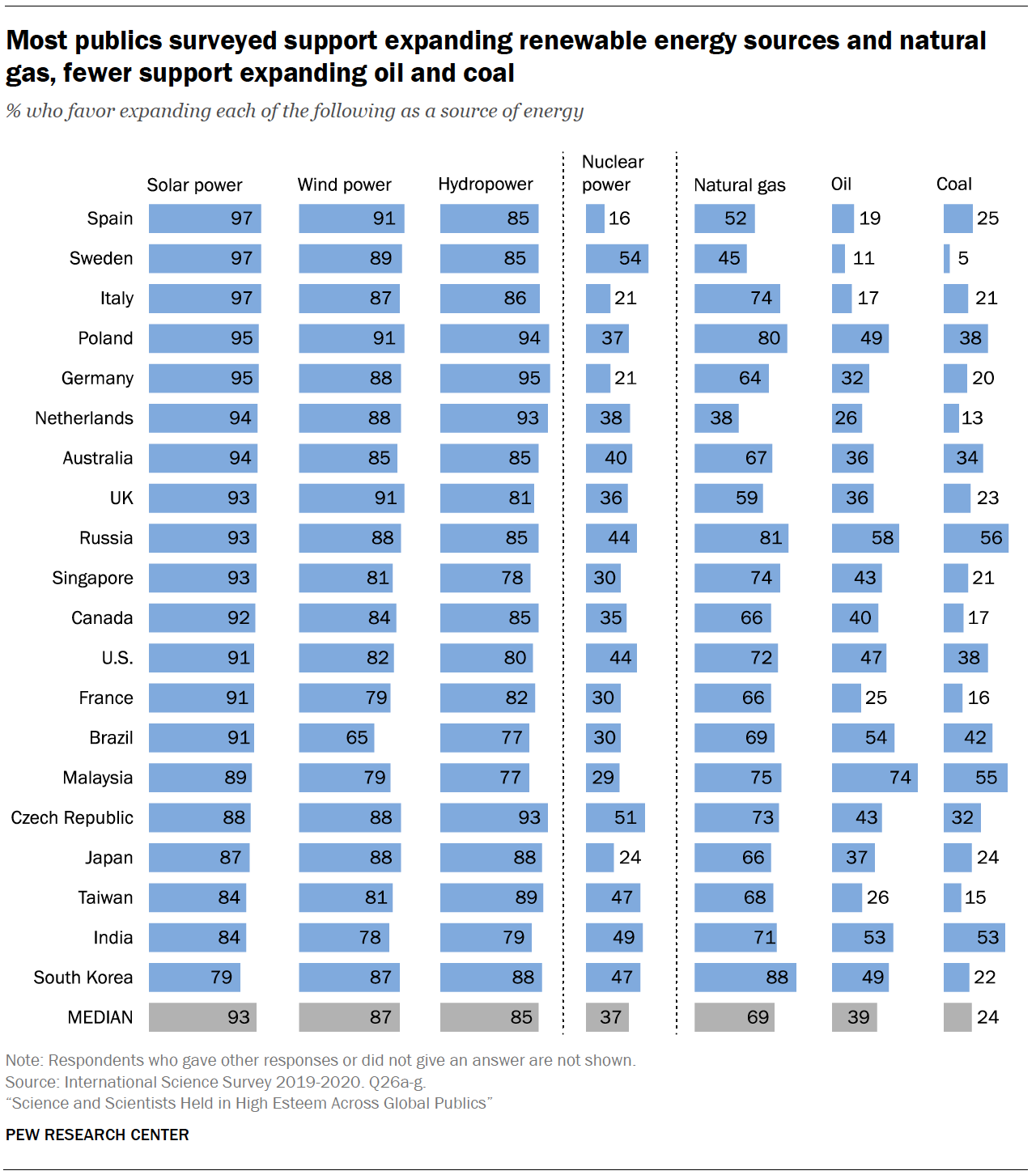

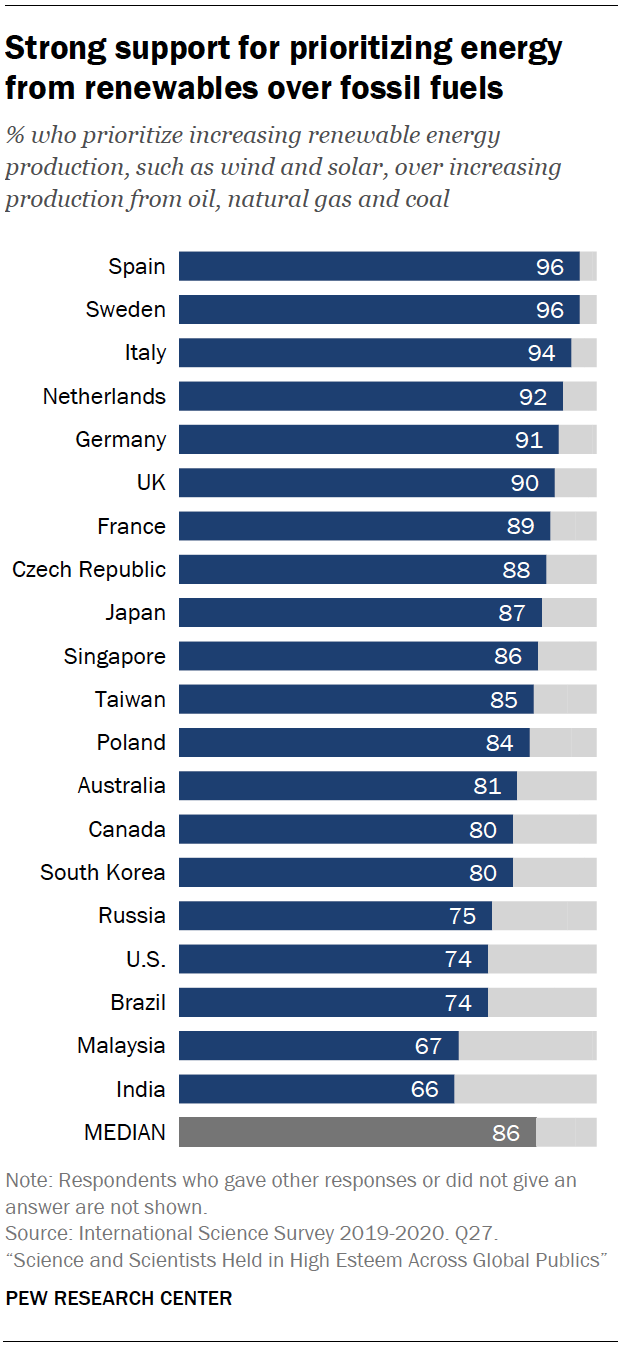

Further, as people think about energy issues, many more would prioritize expanding renewable energy production over that for fossil fuel energies. Views about specific energy sources underscore this pattern, with strong majorities in favor of expanding the use of wind, solar and hydropower sources and much less support, by comparison, for energy sources such as oil or coal.

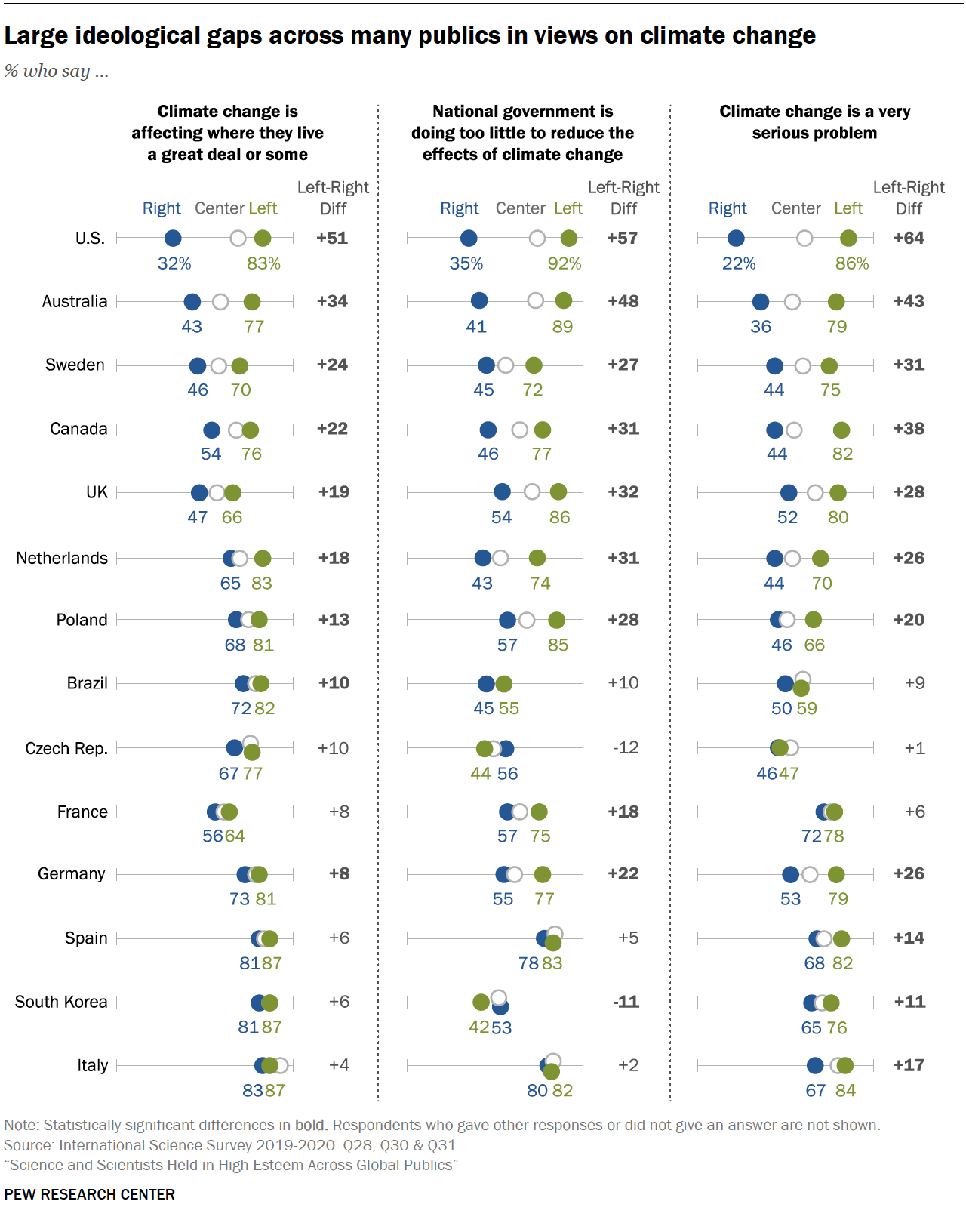

People’s views on climate, environment and energy issues tend to align with their political ideology. Those who place themselves on the left are more inclined to see climate change as a serious problem and to think their government is doing too little to address it. Left-leaning adults are especially inclined to prioritize protecting the environment or creating new jobs and to think it more important to increase renewable energy production over that for fossil fuels.

There is also a tendency for environmental and energy priorities to vary with age. In particular, a larger share of younger adults than older ones across most of these publics prioritize protecting the environment even it means harm to economic development.

Majorities see at least some effects of climate change where they live; a median of 58% say government action to address climate change is insufficient

A median of 70% across the 20 publics surveyed say they are experiencing a great deal or some effects of climate change in the area where they live. Italians and Spaniards stand out. More than eight-in-ten Italians (86%) say climate change is affecting the area where they live at least some, including 55% who think climate change is having a great deal of influence. A similar share of Spaniards say climate change is affecting their local area at least some (84%, including 53% who say climate change is affecting where they live a great deal).

Those in two northern European nations, the UK and Sweden, are far less likely to say they are experiencing the effects of climate change. In Sweden, for example, 55% say they experience a great deal (16%) or some (39%) effects of climate change where they live.

Overall, majorities across most of these publics believe their national government is doing too little to address climate change. A 20-public median of 58% say their national government is doing too little, compared with a median of 27% who say their government is doing about the right amount and a median of just 6% who say it is doing too much to reduce the effects of climate change.

Those in Spain and Italy again stand out. About eight-in-ten Spaniards (82%) and Italians (81%) say their government is doing too little on climate change. Only 14% in both Spain and Italy say their government is doing the right amount. Six-in-ten or more in other places, including the UK (69%), Poland (67%), France (63%), Germany (63%), the U.S. (63%), Canada (60%) and Taiwan (60%), say their government is doing too little.

Places where fewer than half see a need for more government action on climate change include Malaysia, Singapore and India. In Singapore, more say their government is doing the right amount (45%) to address climate change than say it is doing too little (38%). In Malaysia, similar shares say their government is doing too little (41%) and say it is doing the right amount (39%) now. And, in India, 37% say the government is doing too little, while 15% say it is doing the right amount and 32% say it doing too much to address climate change.

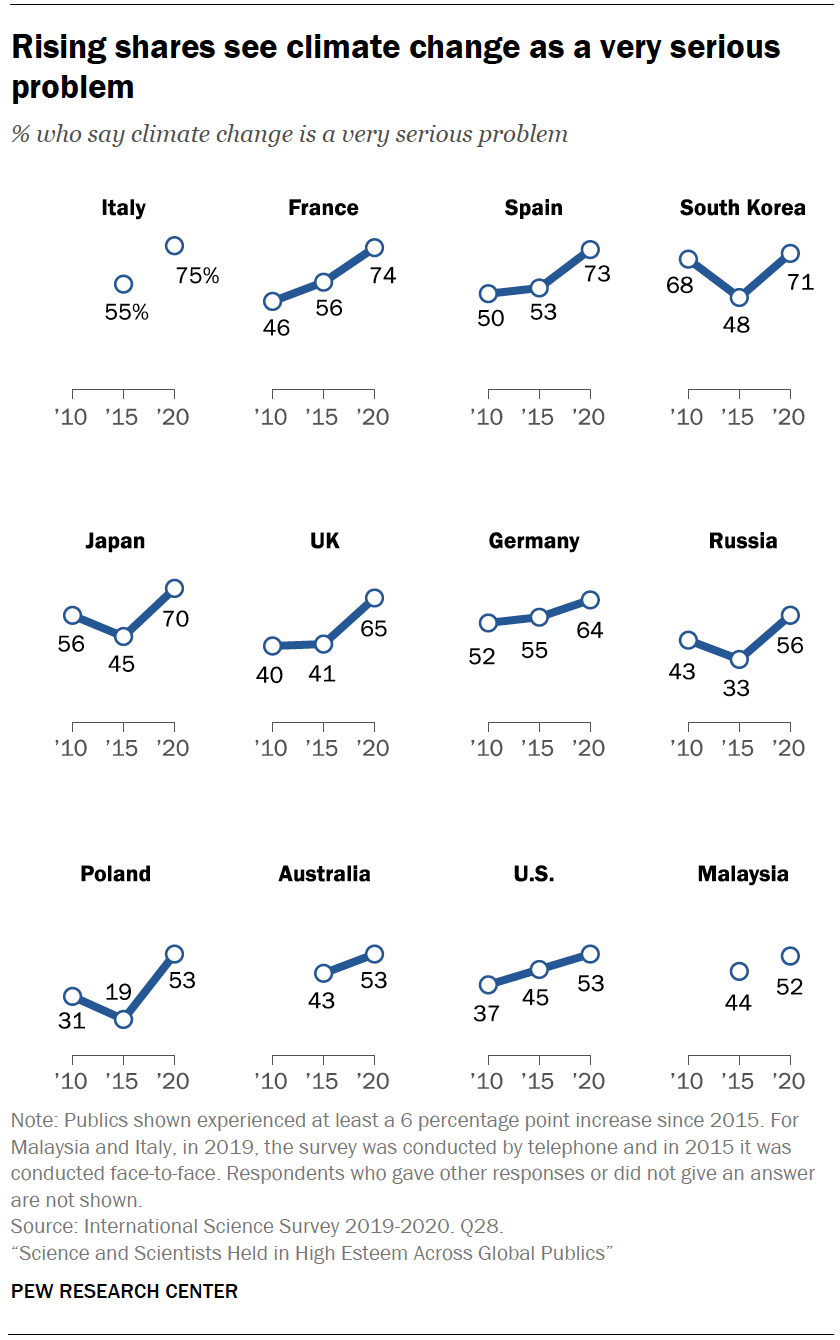

Increasing shares see climate change as a very serious problem since 2015

Climate change is considered a very serious problem by a majority of adults across most of these publics (20-public median of 57%). There is variation in the degree of concern about climate change, however. Large majorities – seven-in-ten or more – in Taiwan (80%), Italy (75%), France (74%), Spain (73%), South Korea (71%) and Japan (70%) see climate change as a very serious problem. By contrast, only about half in Australia (53%), Poland (53%), U.S. (53%), Malaysia (52%), Netherlands (52%) and Czech Republic (49%) say climate change is a very serious problem.

A 2015 Center survey found the U.S. and China stand apart from other nations for their relatively low levels of concern about climate change. In the new survey, too, Americans stand out for having a higher share who say that climate change is not too serious or not a problem (25%).

Concern about climate change is rising across many publics; the share saying climate change is a very serious problem rose in 12 of 15 publics where a comparison is available. In five European countries – Italy, France, Spain, the UK and Poland – the percentage of those who think climate change is a very serious problem has grown by about 20 or more percentage points over roughly five years. For example, in the UK, about two-thirds (65%) now say climate change is a very serious problem, compared with roughly four-in-ten (41%) in 2015. Marked increases in the share saying climate change is a very serious problem also occur in South Korea and Japan (up 23 and 25 percentage points, respectively).

These findings are consistent with past Pew Research Center surveys using different question wording, which showed that global perceptions of climate change as a threat increased between 2013 and 2018. In the U.S., public concern about climate change has also gone up over time; however, concern has risen primarily among Democrats and not Republicans.

People’s views about climate change are strongly linked to political ideology

Global perspectives on climate are strongly aligned with people’s ideological leanings; those on the left are more inclined than those on the right to see climate change as a serious problem and to think their government is doing too little to address it.

Ideological divides in the U.S. are larger than in any other public surveyed. Wide differences among Americans are also seen when comparing conservative Republicans with liberal Democrats. Political differences have been a hallmark of Americans’ views on climate. But other publics also have wide ideological divides over climate matters, consistent with past Center findings.

Australians on the left are more than twice as likely as Australians on the right to say climate change is a very serious problem (79% vs. 36%). Similarly, Canadians on the left are 38 percentage points more likely than Canadians on the right to say climate change is a very serious problem (82% vs. 44%). And in five European countries (Sweden, UK, Germany, Netherlands and Poland), those on the left are 20 or more points more likely than those on the right to say climate change is a very serious problem.

Views on climate change are widely shared among older and younger adults. There is a modest tendency for younger adults (at or under the median age) to say climate change is a very serious problem compared with older adults in a handful of places, including Australia, Canada, UK, the U.S. and others.

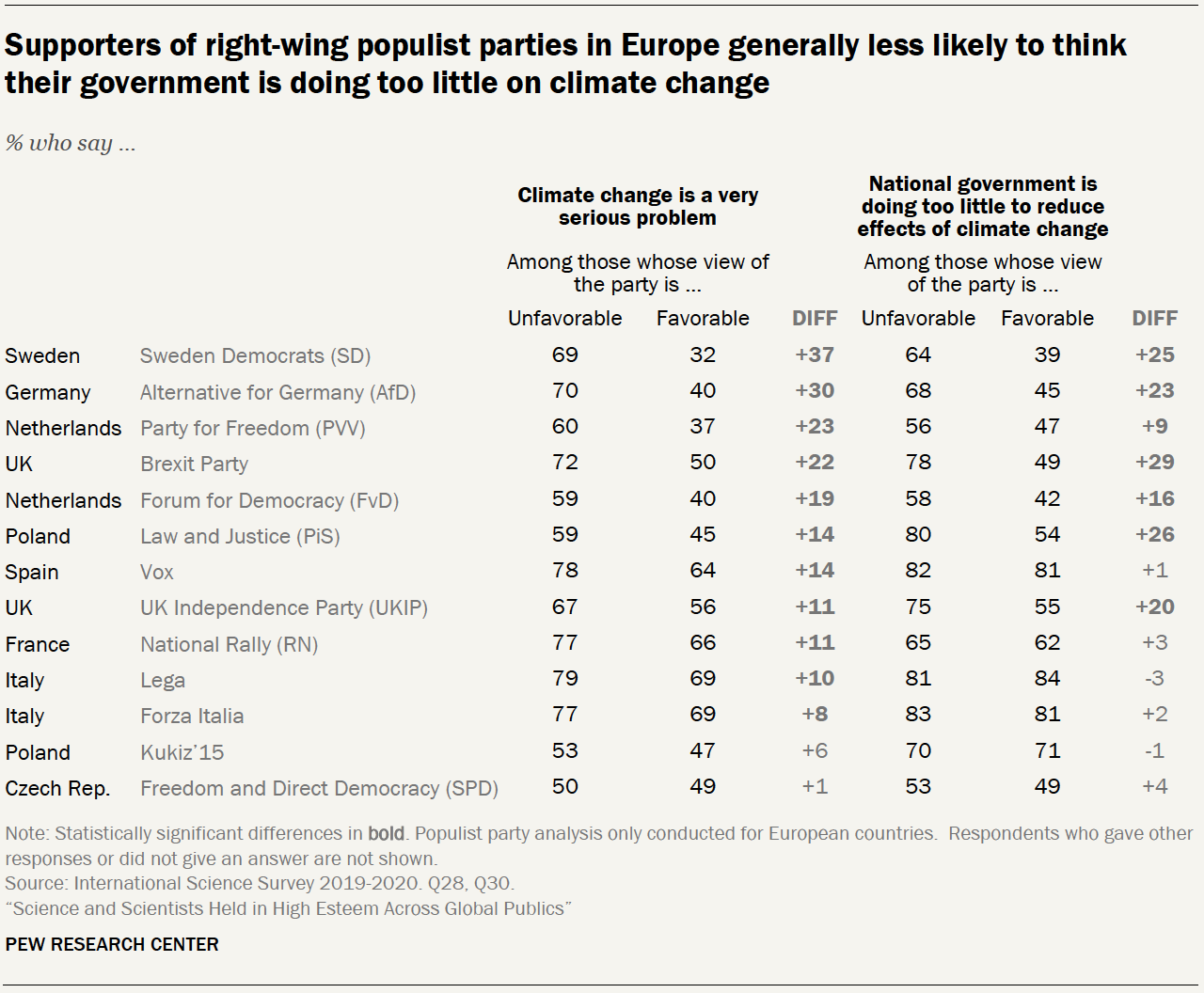

Supporters of right-wing populist parties show less concern about climate change

In Europe, those who hold favorable views of right-wing populist parties generally see climate change as a less serious problem. For example, about one-third (32%) of supporters of Sweden Democrats (SD) say climate change is a very serious problem. In comparison, roughly seven-in-ten (69%) of Swedes who do not support SD say climate change is a very serious problem. Similarly, supporters of right-wing populist parties have drastically different views about how much their government is doing on climate change. In the UK, 49% of those who support the Brexit Party think the government is doing too little on climate, compared with 78% of those who do not support the party.

Large majorities see environmental problems where they live; a median of 71% would prioritize environmental protection over job creation

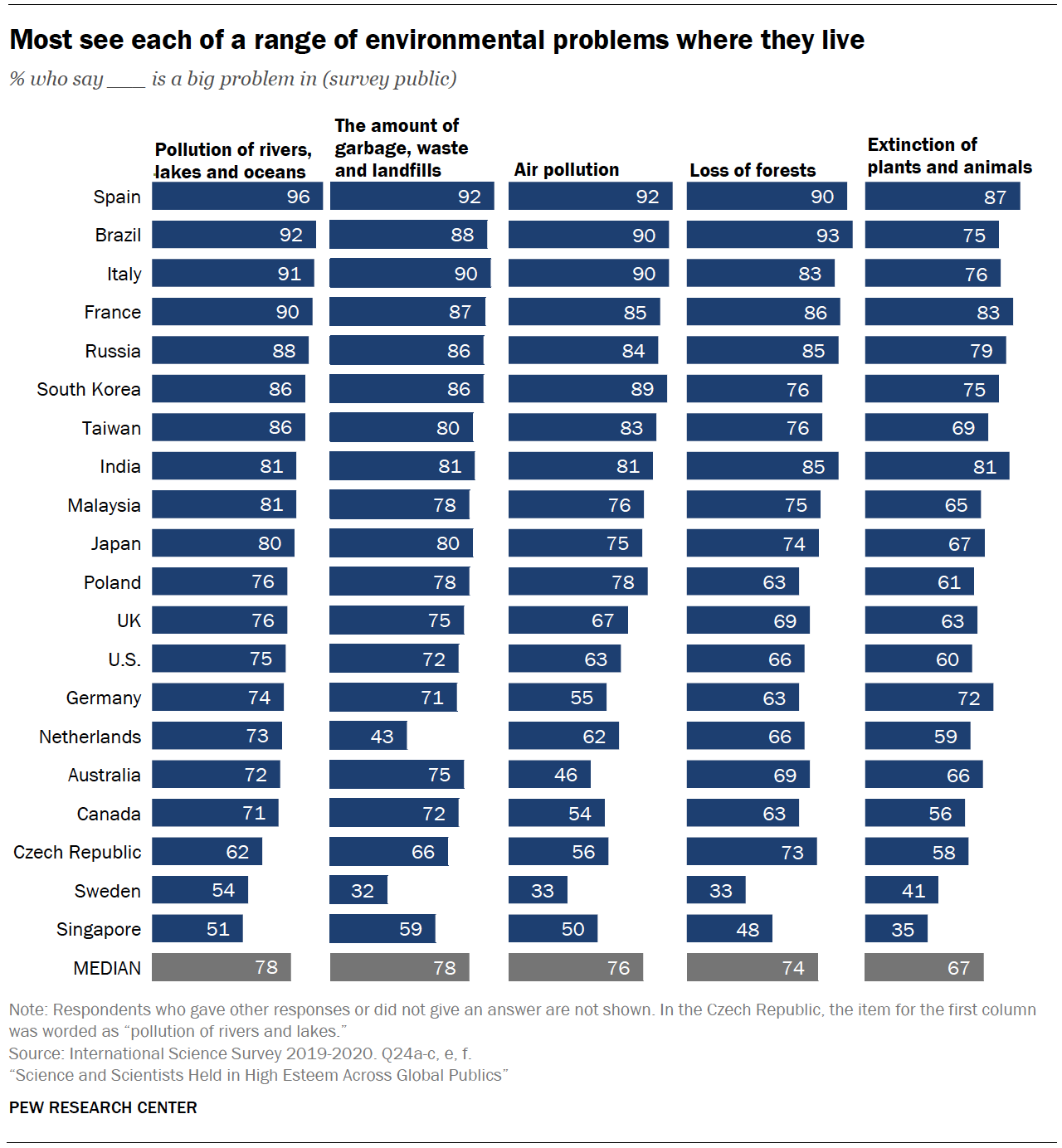

In most of these survey publics, large majorities classify a range of environmental issues as a big problem where they live. Majorities in 18 out of 20 survey publics see pollution of rivers, lakes and oceans as a big problem (20-public median of 78%). Nearly all in Spain (96%) and about nine-in-ten in Brazil, Italy, France and Russia say this. Swedes and Singaporeans are less concerned about water pollution, by comparison. In Sweden, for example, 54% say this is a big problem, 29% say it is a moderate problem and 16% say it is either a small problem or not problem.

There is a similarly high level of concern about the amount of garbage, waste and landfills. Around nine-in-ten say this is a big problem in Spain, Brazil and Italy. Across 17 of the 20 publics, two-thirds or more consider this is a big problem. The Dutch (43%) and Swedes (32%) have lower levels of concern about this issue.

Public concern about other environmental issues is also high, including air pollution (20-public median of 76% say this is a big problem), the loss of forests (74% median) and extinction of plant and animal species (67% median).

Swedes are less likely to consider each of these issues to be a big problem where they live. In Sweden, roughly a third see landfill waste, air pollution and loss of forests as a big problem – the lowest percentage among survey publics for these three items.

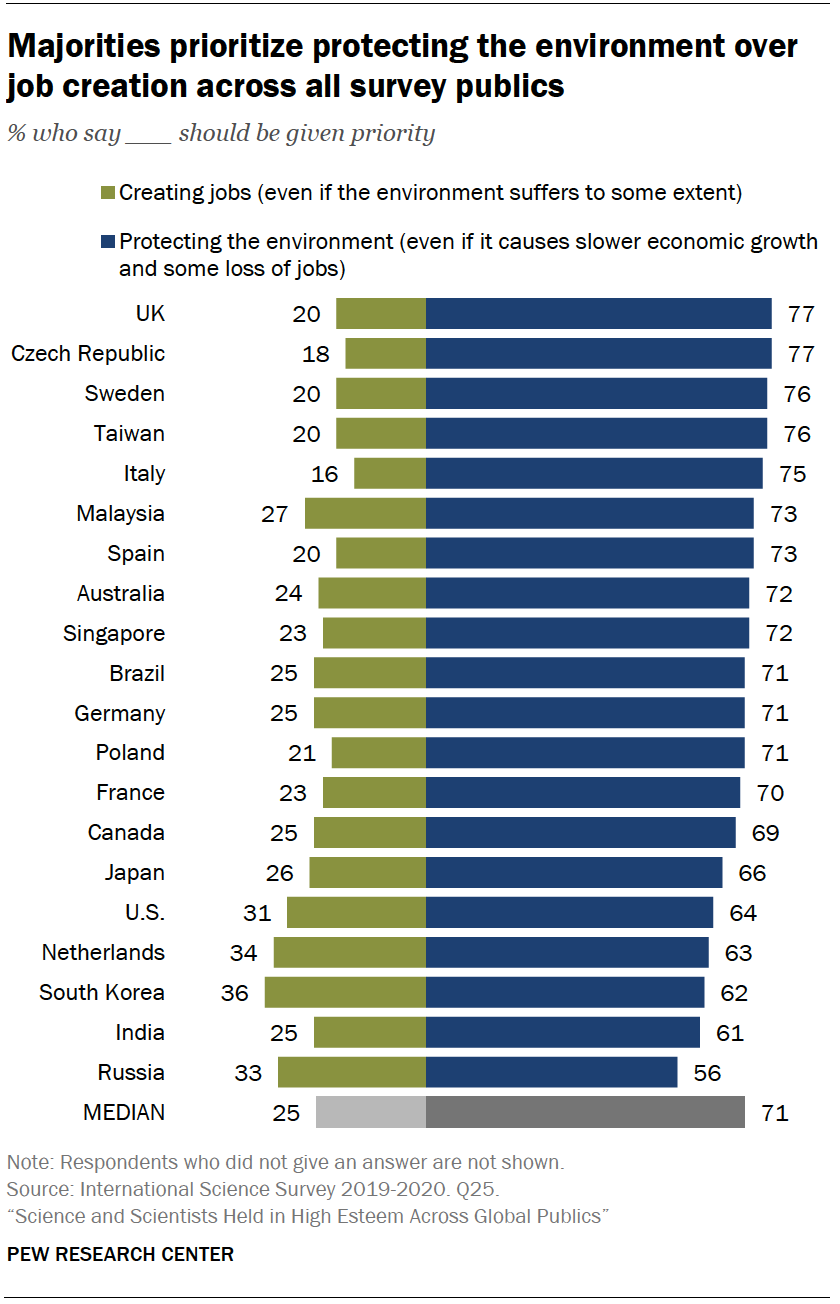

If asked to choose, majorities across all of these publics say they would prioritize protecting the environment even if it causes slower economic growth. A median of 71% would prioritize environmental protection, while a quarter would prioritize job creation.

Public priorities on environmental protections have risen over time. In 18 of the 19 survey publics with a comparable survey trend, the share who would prioritize protecting the environment went up since 2005/2006.

The exception is Canada, where 69% would prioritize protecting the environment, about the same as said this in a 2006 World Values Survey. (All trend comparisons to surveys conducted by the World Values Survey or the Asian Barometer Survey. Note that these surveys used different ways of contacting survey respondents over time and such differences in survey mode can influence findings.) (See Appendix A for details.)

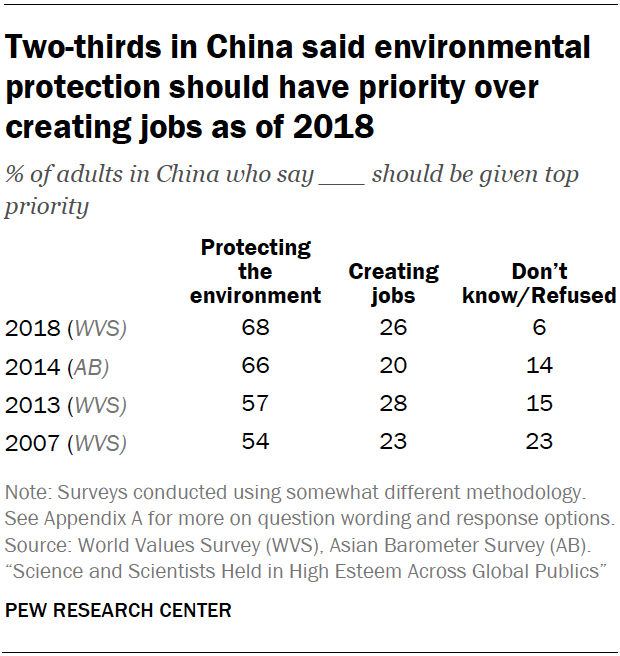

In China, a World Values Survey from 2018 showed a similar balance of opinion: 68% would prioritize protecting the environment, while 26% would prioritize creating jobs. The 2014 Asia Barometer survey found a similar pattern.

Public priorities related to the environment are strongly aligned with political ideology. People who think of their political views as on the left are much more likely than those on the right to prioritize environmental protection over job creation. Ideological differences are particularly wide in the U.S., Canada, Australia and the Netherlands (differences of at least 30 percentage points). This pattern is in line with wide differences by ideology on a range of climate, environment and energy issues. (Ideological self-placement is asked in 14 of the 20 publics; it is not asked in many of the Asian publics.)

There are also differences by age across 12 of the 20 survey publics, with younger adults more likely than older adults to say that protecting the environment should be given priority. The difference is largest in the Netherlands (16 points) and the U.S. (15 points). In Spain, Brazil and Australia, there is a 13-point gap. See details in Appendix A.

Most adults across these publics would prioritize renewable energy sources over fossil fuel production

The United Nations’ sustainability goals on climate emphasize a need to “decarbonize” all aspects of the economy. The Center survey finds majorities across all 20 publics surveyed support the idea of prioritizing renewable energy production over that from oil, natural gas and coal sources.

Across the 20 publics, a median of 86% would prioritize renewable energy production, from sources such as wind and solar, while a median of just 10% would prioritize fossil fuel production. In Spain and Sweden, there is near consensus over prioritizing renewable energy production (96% each). In Malaysia (67%) and India (66%), about two-thirds say the same.

As with beliefs about climate change, people on the left are more likely to prioritize renewable energy production than those on the right. See details in Appendix A.

When asked for their views about each of seven energy sources, a similar portrait emerges. Strong majorities support expanding solar power (20-public median 93%), wind power (median 87%) and hydropower (median 85%).

Views on other energy sources are mixed. Support for expanding the use of natural gas ranges from a high of 88% in South Korea to a low of 38% in the Netherlands. Demand for natural gas has increased around the world over the last decade, in part from an interest in its lower carbon footprint. Across the 20 survey publics, a median of 69% support expanding the use of natural gas.

Public support for expanding the use of oil or coal is considerably lower. Medians of 39% and 24%, respectively, favor expanding reliance on oil and expanding the use of coal. Majorities in Russia and Malaysia support expanding the use of both energy sources, however. The two countries are major producers of fossil fuels. Russia is the world’s largest producer of crude oil and third-largest exporter of coal. Malaysia is the second-largest oil and natural gas producer in Southeast Asia.

Public opinion on nuclear power is quite varied. In Sweden, the Czech Republic and India, about half the public favors expanding nuclear power. In Japan, where the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident led the government to drastically decrease reliance on nuclear power, 24% favor expanding nuclear power and 68% oppose it. The accident also led to reappraisals of nuclear energy production in other countries, including Germany (21% favor expanding), Italy (21%) and Spain (16%), which, along with Japan, are among the publics with the lowest support for expanding nuclear power.

Men tend to be more supportive of nuclear power than women. Swedish men are 31 percentage points more likely than Swedish women to favor expanding nuclear power, for example. Differences between men and women are also sizable in Australia (31 points), the Netherlands (30 points), Canada (27 points) and the U.S. (27 points). Gender differences on nuclear power are consistent with those in past surveys on this topic, including a 2008 Eurobarometer survey, which found men were more supportive of energy production from nuclear power stations across Europe.

As with views about climate and the environment, people’s views about energy issues also tend to vary with their ideology. Across many of the publics, where ideology ratings are available, those on the left express are less likely than those on the right to favor expanding fossil fuel energy sources.