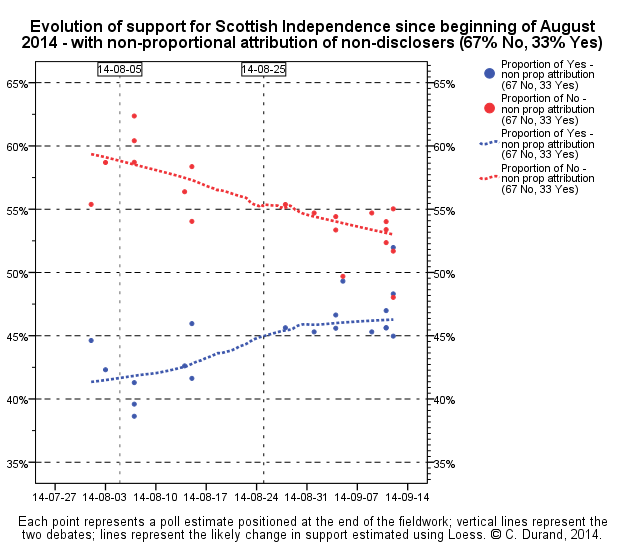

As the Scottish independence referendum comes down to the wire, the “Yes Scotland” and “Better Together” campaigns are furiously trying to win over any remaining undecided voters. Several polls in recent weeks have showed pro-independence sentiment surging, after months in which the pro-union forces appeared comfortably ahead. Interpreting the blizzard of survey data, though, is challenging even for UK analysts, much less those of us on the other side of the Atlantic.

Claire Durand, a sociology professor at the University of Montreal and secretary-treasurer of the World Association for Public Opinion Research, has been tracking and commenting on the Scottish polling on her blog, Ah! les sondages (Ah, polls). We spoke with her Tuesday about the polls, parallels between the Scottish vote and Quebec’s past sovereignty referendums, and more; the excerpts below have been edited for clarity.

Give us a sense of the state of the polling landscape in Scotland — who’s been polling and what methods are they using?

You have mainly six pollsters, though a new one just appeared this week. TNS-BMRB does face-to-face surveys, Ipsos MORI does telephone polls, and the four other big pollsters — Survation, Panelbase, ICM and YouGov — were all opt-in online only, though ICM and Survation started doing telephone polls in the last few days. The pollsters are very well-known.

How have the online polls differed from those using more traditional methods?

The opt-in polls overall were more favorable to the “yes” (pro-independence) side until about a month ago. The opt-in polls had “yes” at three to five percentage points higher than regular polls, but since August I haven’t seen a difference. There have been 15 opt-in polls and five face-to-face or telephone polls since August.

[During the 1995 Quebec sovereignty campaign]

Why do you think the online polls now look more similar to the traditional polls?

[their raw data]

But beyond that, what I see when I look at the spectrum of poll results is that the closer we get to referendum day, the more the results (from all the polls) are converging.

When you analyze the poll results, you attribute two-thirds of undecided voters (which you call “non-disclosers”) to the “No” side and one-third to the “Yes” side, arguing that people who oppose independence are less likely to tell that to a pollster. What’s your reasoning there?

[Oxford sociologist]

You also note that young people (16- to 34-year-olds) are more likely to say they support independence. Why were you particularly interested in young people’s attitudes? Do the polls show any other interesting demographic or geographic divisions?

In Quebec today, young people are not more sovereigntist than older people, and when I first started talking with people in Scotland, they told me it was the same thing there — “Young people live in a globalized world, they’re not interested in sovereignty, blah blah.” I wanted to see if that would be true, and in fact it isn’t. In Quebec in 1995 and in Scotland today, young people are both more sovereigntist and more likely to be swayed by the arguments of the “Yes” side. This is quite normal — when you are a young person, you’re more interested in change.

Women are systematically more inclined to vote “No,” and this was the case in Quebec as well. It’s not a huge difference, but you see it in almost all the polls. And people who were born outside Scotland are more likely to vote “No,” but it’s nothing like the divide in Quebec between francophones and non-francophones (who almost unanimously opposed sovereignty).

Your most recent post is titled “Yes Scotland: Ceiling reached?” Besides the issue with undecideds, why do you think polls may be overstating the actual Yes vote?

In Scotland, the “No” side did not move that much over the past year and was always well ahead. Then suddenly, in the past two weeks, the “Yes” side went up like it did in Quebec in 1995, and some polls showed “Yes” ahead. When people see that there is a possibility that “Yes” will win for real, they realize that voting “Yes” isn’t the same as saying in a poll that you’ll vote “Yes.” A vote has very real consequences, and when some people see that they start thinking about the risks and they’ll back off. I maintain my prediction: If I see the “Yes” side getting something like 55% in the polls, then I might believe they will win.