As the federal government gears up to offer deportation relief to about 4 million unauthorized immigrants, it’s worth looking back to 1986, when a new law established what was then the biggest legalization and citizenship process in U.S. history. One similarity between then and now: No one knows how many people will apply.

However, it’s problematic to use the application rate under the 1986 law as a guide to predict uptake today for President Obama’s various deferred action programs. Although experts now believe that about three-fourths of those eligible for general legalization did apply under the 1986 law, there were no reliable statistics at the time about the size of the unauthorized immigrant population or how many were eligible.

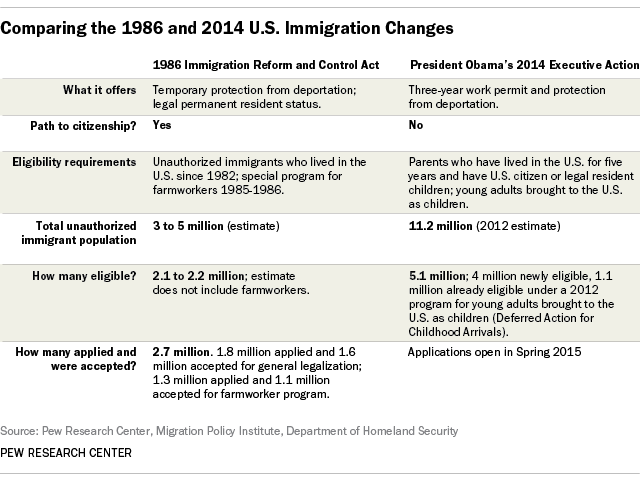

To be sure, the 1986 Immigration and Control Act provided more benefits to a broader group of unauthorized immigrants than President Obama’s new program, and also included expanded border security and enforcement. The law offered legal permanent residency (a green card) and the option to apply for citizenship to unauthorized immigrants who met certain conditions. Ultimately, nearly 2.7 million people got green cards under either the law’s general legalization program or its special program for farm workers. About 1.1 million of the green card recipients later became U.S. citizens, according to a 2010 analysis by the Department of Homeland Security.

Although President Obama’s program is available to many more people than the 1986 law was, it’s substantially different in that it does not allow applicants legal status or a path to become citizens. Obama’s program will offer three-year work permits and relief from deportation to unauthorized immigrants who have U.S.-born children or legal permanent resident children and have lived in the U.S. for at least five years. The president also expanded a program already in place that offers work permits and deportation relief to young adults brought to the U.S. as children. An estimated 4 million of the nation’s 11.2 million unauthorized immigrants qualify for the new program, according to Pew Research Center estimates.

In 1986, though, the estimates of eligibility were much fuzzier. There was little census data about immigrants, which is the basis for the population estimates. And with those data constraints, government officials and researchers could not easily estimate the size of the unauthorized immigrant population.

The then-Immigration and Naturalization Service initially forecast that 2 million to 3.9 million people would apply for the general legalization program, according to congressional testimony. But that top figure is close to the total estimated population of unauthorized immigrants at the time — 3 to 5 million people. The government eventually reduced its estimate to a closer figure to the 1.8 million who eventually applied, and 1.6 million who were approved.

One problem with gauging eligibility for the 1986 law was that the program rules kept changing. The government rewrote the regulations spelling out the application process several times, leaving potential applicants wondering whether they were eligible, according to a 2014 report by the Migration Policy Institute. The last lawsuit challenging those regulations was not settled until 2008.

Early participation was lower than expected, so the immigration agency paid recruiter fees to community groups for sending applicants to more than 100 legalization offices it had set up. In its congressional testimony, the Government Accounting Office cited studies that said some unauthorized immigrants did not apply because they did not think they were eligible; others said they did not have the money for application fees, did not know how to apply, feared the immigration agency or were concerned their family could be separated because some were eligible and others were not.

Applicants for temporary general legalization had to have lived in the U.S. continuously since Jan. 1, 1982, and meet other conditions including demonstrating “good moral character” and ability to support themselves; to get legal permanent residency they also had to demonstrate knowledge of English and American civics.

The rules were much looser for the farm worker program. Applicants had to show they had done 60 days of qualified seasonal farm work in a year, but did not have to meet language or civics requirements to apply for legal permanent residence.

The number who applied under the farm worker program — 1.3 million — was far higher than had been estimated. There were 700,000 applicants in California alone, more than the number of all farm workers in the state at the time, according to an analysis by immigration scholar Philip L. Martin. He and others suggested there was widespread fraud in this program. Martin has reported, for example, that entrepreneurs at the Mexican border rented farmworker clothing to potential applicants and coached them on how to present themselves to immigration examiners.

The naturalization rate for unauthorized immigrants under the 1986 law was lower than for other immigrants who obtained green cards through traditional channels around the same time. A Department of Homeland Security analysis pointed out that a high share of these immigrants were born in Mexico. Overall, Mexican-born legal immigrants historically and currently have had a far lower naturalization rate than immigrants from other countries. In 2011, for example, 36% of legal immigrants from Mexico had been naturalized, compared with 68% of others, according to census data analyzed by the Pew Research Center. The same general pattern was true in the 1980s.

But once you account for the high share of those born in Mexico, immigrants who received legal status under the 1986 law’s general legalization program were more likely to become citizens than were other immigrants at the time. Mexican-born immigrants’ citizenship intentions are important because today they are both the largest group of legal permanent residents in the U.S. and the majority of the nation’s unauthorized immigrants — 5.9 million of the 11.2 million total in 2012, according to Pew Research Center estimates.

According to Pew Research analysis, Mexican-born unauthorized immigrants are disproportionately likely to benefit under President Obama’s new program. About two-thirds of those who could benefit are unauthorized immigrants from Mexico. An estimated 44% of unauthorized immigrants from Mexico could apply for deportation protection, compared with 24% of those from other parts of the world.