The two largest organized Jewish denominations in America – Reform and Conservative Judaism – together have about five times as many U.S. members as the historically much older, more strictly observant Orthodox community. But the Reform and Conservative movements have a far smaller footprint in Israel, according to Pew Research Center’s new survey of religion in Israel.

This is only one of many differences between the Jewish populations of Israel and the U.S., the world’s two largest. Together, these countries are home to about 80% of the world’s Jews, but American and Israeli Jews do not always look the same in terms of their political beliefs, levels of religious observance, social circles and even their definitions of what it means to be Jewish.

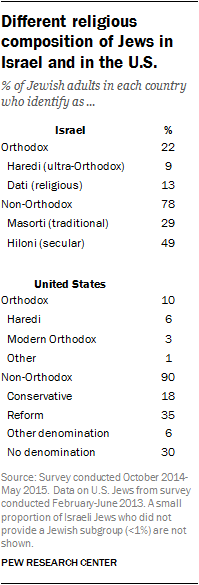

Jewish affiliation with Conservative and Reform synagogues and congregations is one of the most notable ways in which Jewish life in the U.S. differs from that in Israel. About half of Jewish Americans identify with either the Reform (35%) or Conservative (18%) movements, both of which developed in recent centuries in Europe and North America as generally less pious alternatives to the ancient Orthodox tradition. Only about 10% of U.S. Jews are Orthodox.

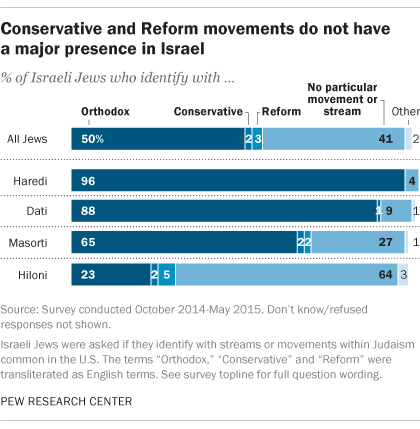

The survey asked Jews in Israel whether they identify with any of these international streams of Judaism, acknowledging that some of them may not be familiar to respondents. In Israel, very few Jews identify with Conservative (2%) or Reform (3%) Judaism, while half (50%) identify with Orthodoxy – including many Jews who are not highly religiously observant but may still be most familiar with Orthodox Judaism. About four-in-ten Israeli Jews (41%) do not identify with any of these three streams or denominations of Judaism.

Instead, Israeli Jews are much more neatly grouped into four informal categories of Jewish religious identity – Haredi (ultra-Orthodox), Dati (religious), Masorti (traditional) and Hiloni (secular). Virtually all Jews in Israel say one of these terms describes their religious category.

In some cases, these four groups are comparable to Jewish subgroups in the U.S. For example, Haredim in Israel exhibit very similar religious beliefs and practices to ultra-Orthodox Jews in the U.S., and both groups are isolated from the rest of society in many ways. And Datiim are much like Modern Orthodox Jews in the U.S., as both groups largely adhere to Jewish law while also integrating with the modern world.

“Masorti” is the Hebrew name for the Conservative movement in Israel. But very few Israeli Jews who give themselves the informal Masorti label also say they are members of the formal international movement known as Conservative Judaism (2%). Israeli Masortim display a wide range of religious commitment, but on average, they are more religiously engaged than U.S. Conservative Jews in some ways and less religious in others. For instance, Conservative U.S. Jews are more likely than Israeli Masortim to say religion is very important in their lives (43% vs. 32%), but less likely to say they keep kosher at home (31% vs. 86%).

Overall in America, Reform Jews are less devout than Conservative Jews, but they are not quite as secular as Israeli Hilonim, and only 5% of Hilonim identify with Reform Judaism. Most Reform Jews in the U.S. say they go to synagogue “a few times a year” or “seldom” (67%), but the majority of Hilonim in Israel (60%) never attend synagogue. And nearly eight-in-ten Hilonim (79%) say religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives, compared with only 43% of Reform Jews who say the same.

In this way, Israeli Hilonim are more comparable to the 30% of U.S. Jews who do not identify with any Jewish movement or denomination. Among these Jewish Americans, about three-quarters (74%) say religion is not important in their lives.