A quarter-century after the end of apartheid, South Africans will vote in general elections on May 8 against a backdrop of pessimism over the state of their political system and persisting divisions in attitudes by race and political party.

Attitudes toward public institutions in South Africa have become more negative since the early 1990s, following the country’s first democratic elections. These attitudes were captured in a Pew Research Center survey conducted in summer of 2018 and in World Values Survey results from 1990 and 2013, periods before and after apartheid.

The elections are being held at a time when numerous allegations of corruption have characterized South Africa’s politics – most notably against the leading African National Congress (ANC) party.

Here are six facts on South Africans’ attitudes about the state of their nation before the elections:

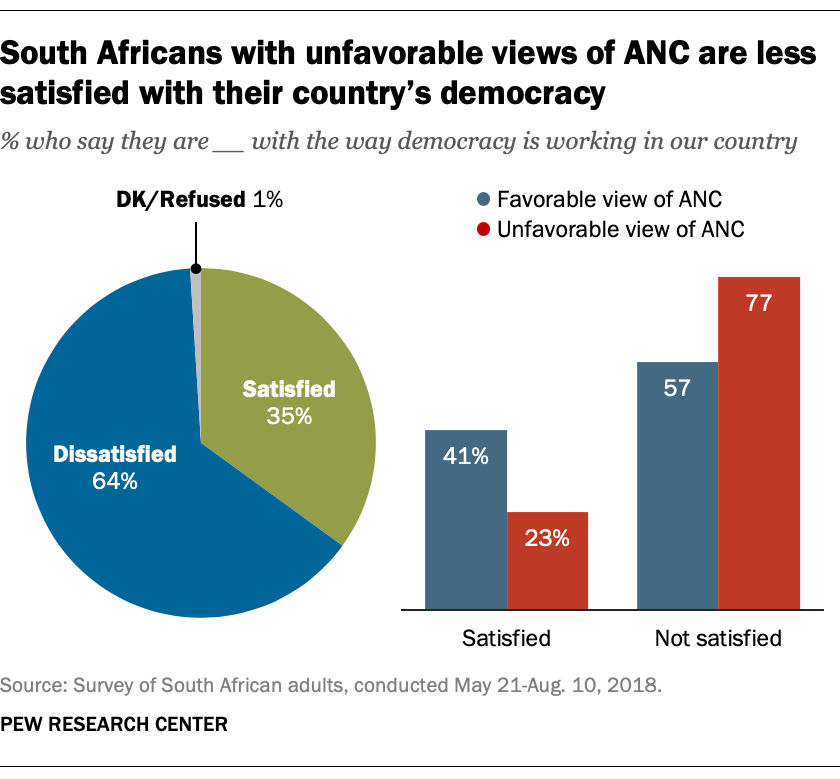

The majority of South Africans are dissatisfied with the state of their democracy. As of 2018, nearly two-thirds of South Africans say they are dissatisfied with their democracy. This contrasts with 2013, when 67% of South Africans said they were satisfied with the way democracy was working in their country.

There is a clear partisan split in satisfaction with the functioning of the country’s democracy. While about four-in-ten of those who see the ANC positively say they are satisfied with South Africa’s democracy, only about a quarter of those who see ANC negatively say the same. Nevertheless, majorities on both sides express dissatisfaction with the country’s democracy.

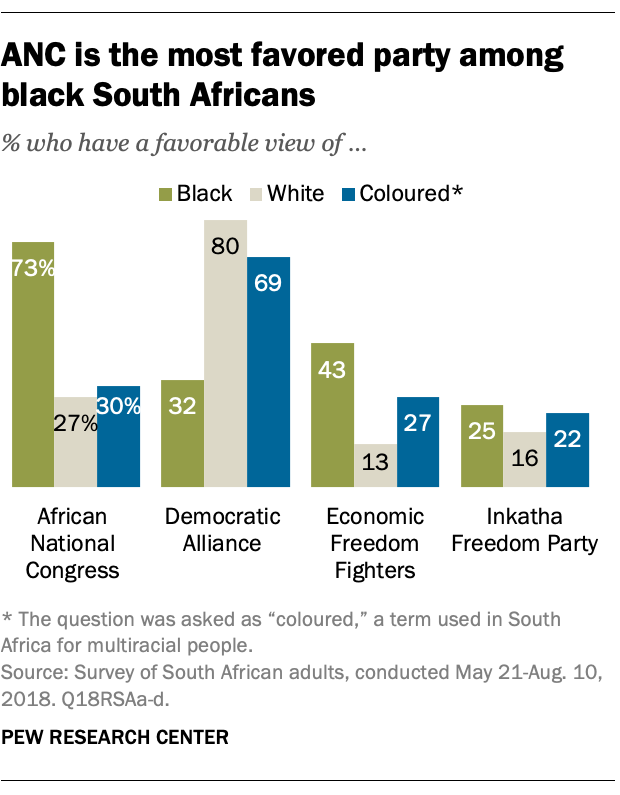

Black South Africans hold significantly more favorable views of the ANC compared with other racial groups. Nearly three-quarters of blacks in South Africa say they hold very favorable or somewhat favorable opinions of the country’s leading party, the ANC – which was once led by the country’s first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, and has historically carried strong support from blacks. By contrast, only 27% of white and 30% of coloured South Africans say they view the ANC favorably. (Note: The term “coloured” is commonly used in South Africa to describe people of multiple races. It is used throughout this post to reflect survey question wording.)

The Democratic Alliance (DA), which has established itself as the main opposition party in this year’s election, garners significantly higher favorability measures among white (80% favorable) and coloured (69%) South Africans as of 2018. Conversely, only about three-in-ten blacks say they have positive opinions of the DA.

The other two parties included in the survey, the Inkatha Freedom Party and the Economic Freedom Fighters, have much lower overall favorability ratings. Fewer than four-in-ten South Africans have favorable views of the EFF (37%) and IFP (23%).

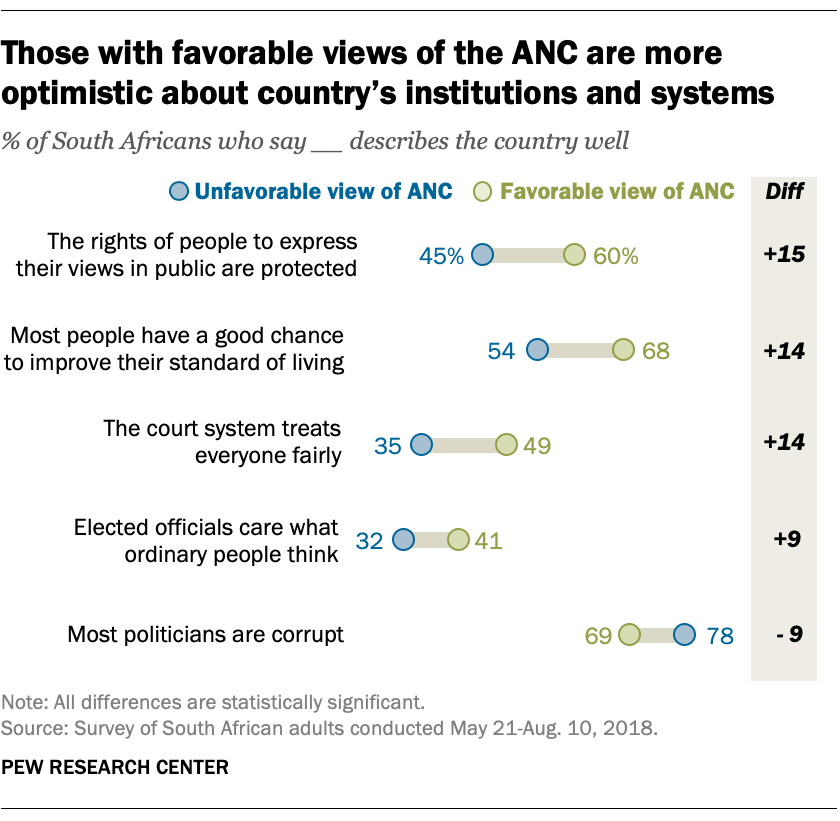

South Africans differ by party in their attitudes toward the country’s political institutions and systems. Those who hold positive opinions of the current ruling party are more likely than people with unfavorable views to say that rights to free speech are protected, that most people are capable of upward mobility, and that the justice system is fair. They are also more likely to say that elected officials care what ordinary people think.

Overall, roughly seven-in-ten South Africans (72%) say that most politicians are corrupt. However, those who view the ANC unfavorably are 9 percentage points more likely to share that view than those who have a positive view of the ruling party.

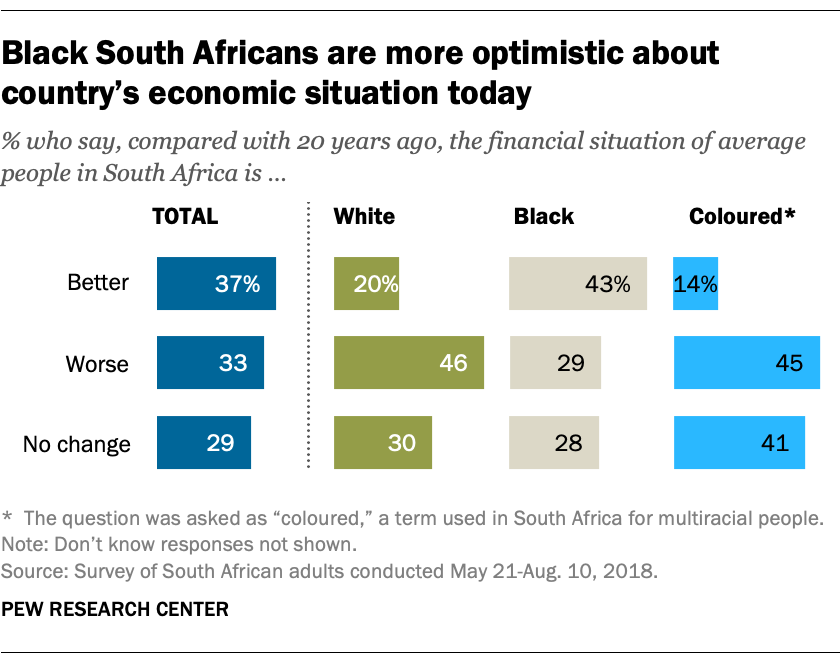

White and coloured South Africans are more pessimistic about the country’s economic situation today than in the past. However, answers to this question vary widely by race. Similar shares of coloured and white South Africans say the financial situation has worsened (45% and 46%, respectively), while only 29% of black South Africans express this sentiment.

These differing perspectives by race come amid debates about land reform, a central issue in South African political discussions. Since coming into office, the ANC has pledged to transfer land from white to black South African ownership to rectify the legacies of land dispossession of the early 20th century. These land reform efforts have been met with varied reactions by South Africans.

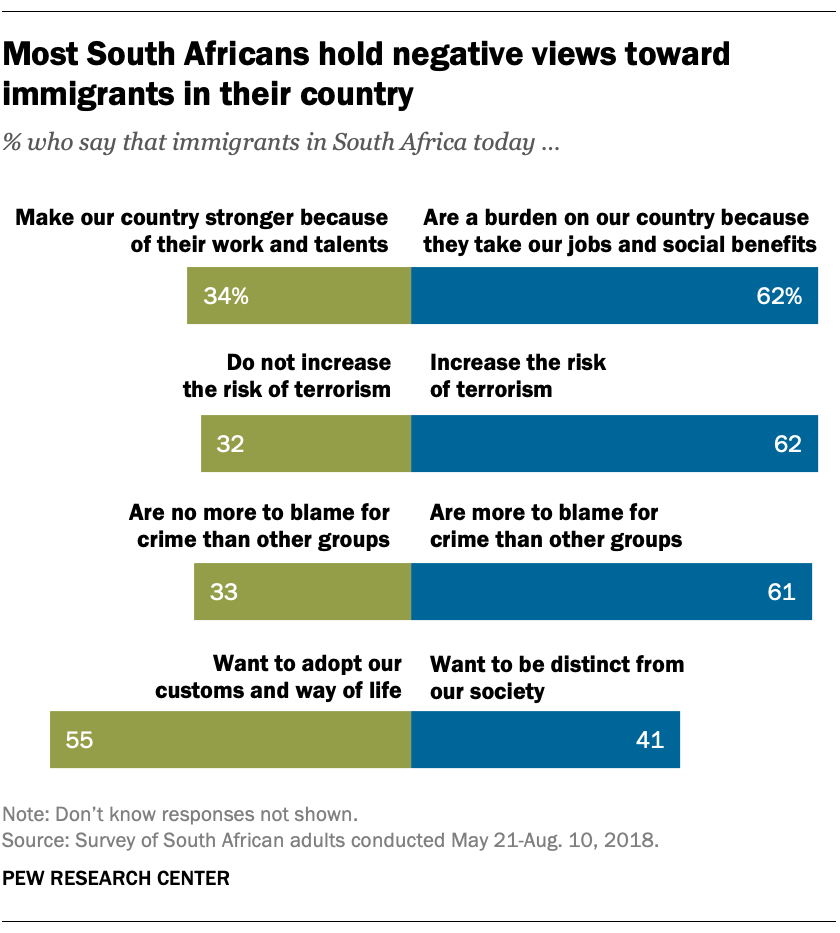

South Africans hold negative views about immigrants for a range of reasons. Between 2010 and 2017, the number of immigrants in South Africa nearly doubled, from approximately 2 million in 2010 to 4 million in 2017. Immigrants account for about 7% of the country’s total population, up 3 percentage points since 2010. Xenophobic attacks have gone on for more than a decade.

In terms of public opinion, a majority in South Africa agrees with the statement that immigrants are a burden on the country because they take jobs and social benefits. Immigrant-related anxiety is also evident when South Africans were asked who is to blame for crime and terrorism, with most saying immigrants are more to blame for crime than other groups in South Africa (61%) and that they are more likely to increase the country’s risk of terrorism (62%). A previous Pew Research Center report found that South Africans are somewhat more negative about immigrants than other publics surveyed. Though a majority says immigrants are burdensome, over half (55%) say immigrants want to adopt South African customs and way of life.

Even so, crime and unemployment are two of the most important problems facing the nation, according to Afrobarometer.

While all racial groups express negative views of immigrants, white South Africans are more likely than those who are black or coloured to say immigrants are a burden for the country. Roughly seven-in-ten white South Africans (72%) say immigrants take jobs and benefits, while 61% and 58% of black and coloured individuals, respectively, say the same.

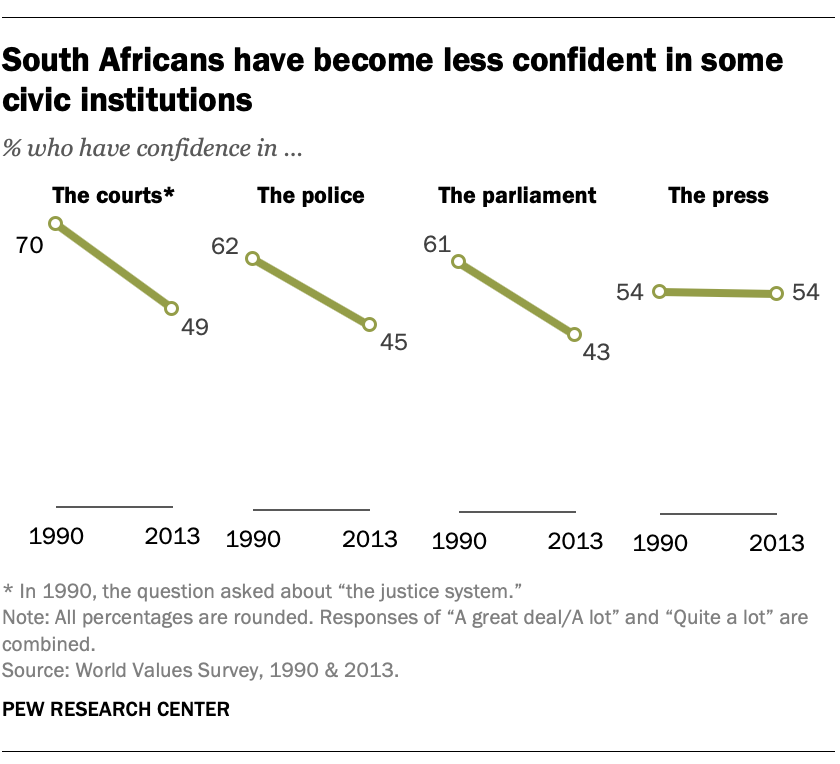

Confidence in some civic institutions declined from 1990 to 2013 – before and after the end of apartheid. Four years before apartheid’s downfall, majorities of South Africans expressed confidence in their public institutions, according to 1990 findings from the World Values Survey. Seven-in-ten said they had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in the courts, and around six-in-ten said the same about the police and parliament.

However, by 2013, only about half or fewer of South Africans maintained these positive views. The shares who said they are confident in their country’s justice system, police and parliament fell by 21, 17 and 18 percentage points, respectively, since the end of apartheid. Attitudes about the press stayed at around the same levels from 1990 to 2013.

Note: See full topline results and methodology here.