As governments around the world turn to technology to help fight the spread of COVID-19, a majority of Americans are skeptical that tracking someone’s location through their cellphone would help curb the outbreak. At the same time, the public holds mixed views on when – and if – this type of monitoring is acceptable.

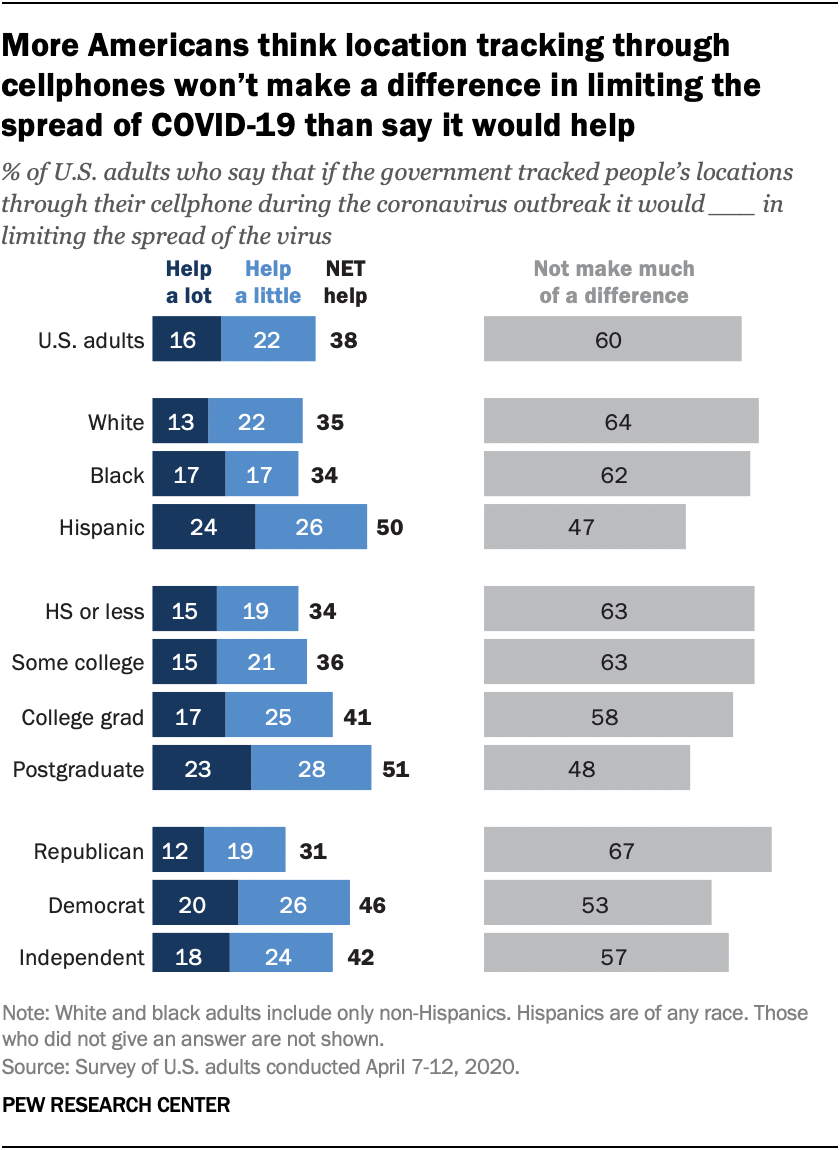

Six-in-ten Americans say that if the government tracked people’s locations through their cellphone it would not make much of a difference in limiting the spread of the virus, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted April 7-12, 2020. Smaller shares of Americans – about four-in-ten – believe this type of monitoring would help a lot (16%) or a little (22%) in limiting the spread of COVID-19.

Across demographic groups, roughly half or more believe this type of tracking would have little impact on slowing the COVID-19 outbreak. Still, Democrats (46%) and independents (42%) are more likely than Republicans (31%) to say that if the government tracked people’s locations through their cellphone during the outbreak it would help at least a little to limit the spread of the virus.

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans think about surveillance and cellphone tracking as it relates to the response to the new coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,917 U.S. adults from April 7 to 12, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Views also differ by educational attainment and by race and ethnicity. About half of postgraduates (51%) believe cellphone tracking would help curtail the spread of COVID-19 to some degree, compared with roughly four-in-ten or fewer of those who have a bachelor’s degree, some college experience, or a high school education or less. And Hispanic adults (50%) are far more likely than their white (35%) or black counterparts (34%) to think this type of government surveillance would be helpful during the outbreak.

Pitting trade-offs between data collection for public good against privacy concerns has emerged as an issue in the coronavirus pandemic. Last month, Israel authorized the use of cellphone location data to help combat the spread of the virus, while some nations have used smartphone apps to ensure that people are complying with quarantine guidelines. In the United States, government officials have used anonymized cellphone data to better understand how the outbreak is spreading in some areas.

These new efforts have been met with some resistance. Advocates have raised concerns about what these practices mean for digital privacy, data security and whether this level of surveillance could remain long after the pandemic.

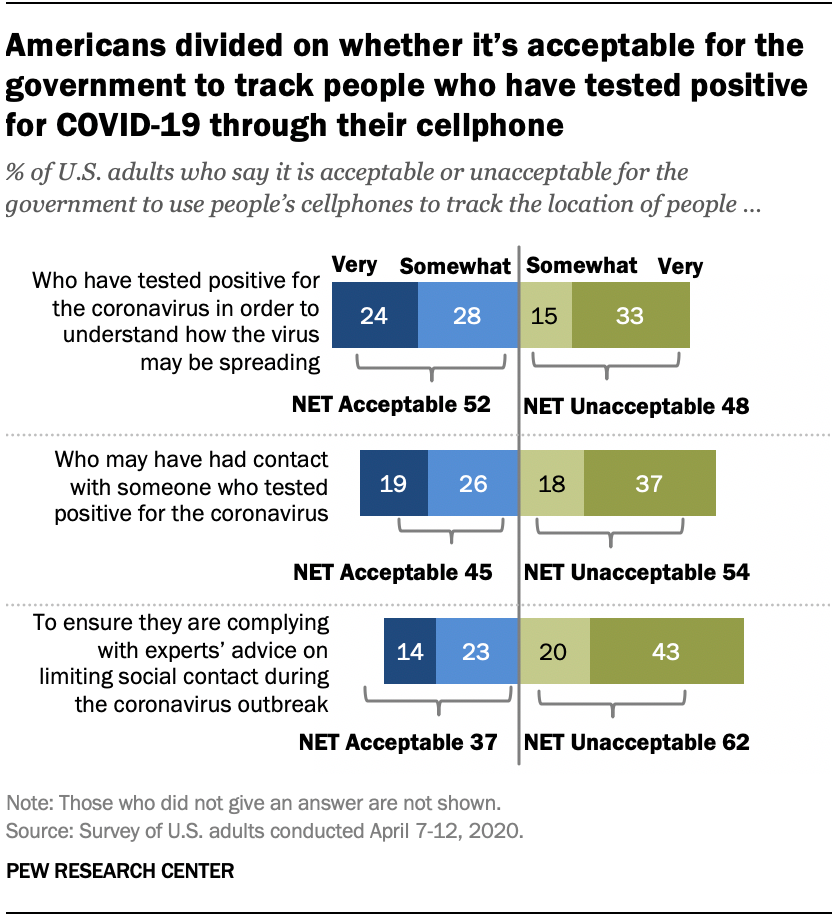

Amid this tension between personal privacy and public safety, 52% of Americans surveyed in early April say it is at least somewhat acceptable for the government to use people’s cellphones to track the location of those who have tested positive for the virus to understand how the virus is spreading, but a similar share (48%) believes this is very or somewhat unacceptable to do. At the same time, 45% of the public says it is acceptable for the government to use cellphones to track the location of people who may have had contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19, while a somewhat larger share (54%) describes this type of tracking as unacceptable.

By comparison, there is less support for monitoring mobile devices to make sure people are following social distancing guidelines. Some 37% of Americans say it is at least somewhat acceptable for the government to use people’s cellphones to track the location of people to ensure they are complying with experts’ advice on limiting social contact during the coronavirus outbreak. But a much larger share (62%) believes this type of cellphone tracking is very (43%) or somewhat (20%) unacceptable.

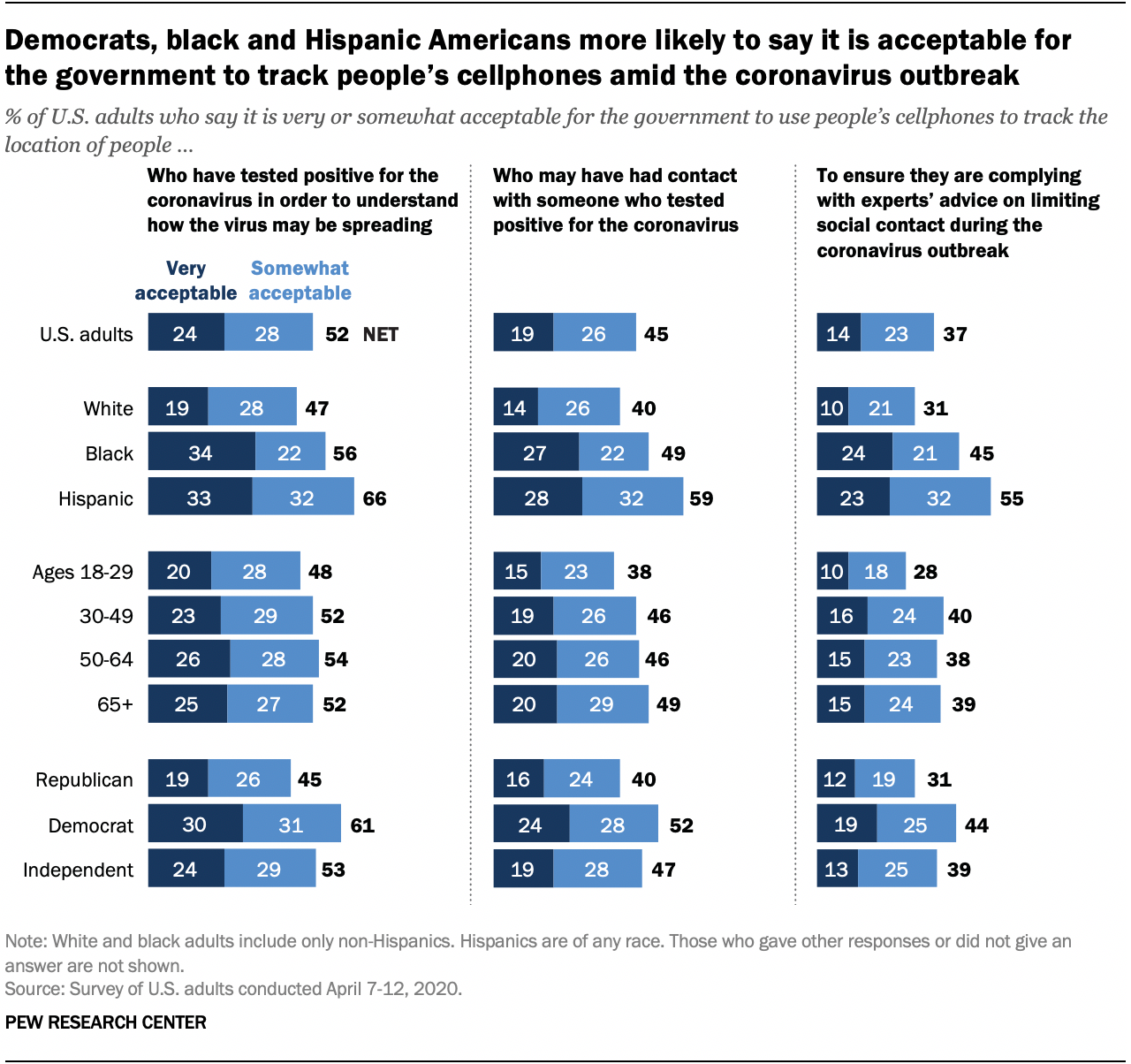

Republicans and Democrats tend to hold contrasting views about the appropriateness of tracking people’s movements during the pandemic. While 61% of Democrats say it is very or somewhat acceptable for the government to use cellphones to track the location of people who have tested positive for the coronavirus in order to understand how the virus may be spreading, that share falls to fewer than half among Republicans (45%). Independents’ views fall in between these two groups.

Democrats are also more likely than Republicans to say it is acceptable for the government to track via cellphone the location of people who may have come in contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19 (52% vs. 40%) or to use this type of tracking to ensure people are complying with experts’ advice on limiting social contact (44% vs. 31%).

Overall, Hispanic Americans are more accepting of these measures than black or white people. For example, 55% of Hispanic adults say it is at least somewhat acceptable for the government to use cellphones to track the location of people to make sure they are limiting social contact during the outbreak, compared with 45% of black adults and just 31% of whites. There are similar patterns by race and ethnicity when asked about location tracking for those who have tested positive for the virus or who may have been in contact with someone who was infected.

Age is also a factor. Americans ages 30 and older are more likely than those ages 18 t0 29 to say it is acceptable for the government to track the location of people through their cellphone to ensure they are complying with experts’ advice on limiting social contact (39% vs. 28%) or to track the location of people who may have had contact with someone who tested positive (47% vs. 38%).

Note: Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.