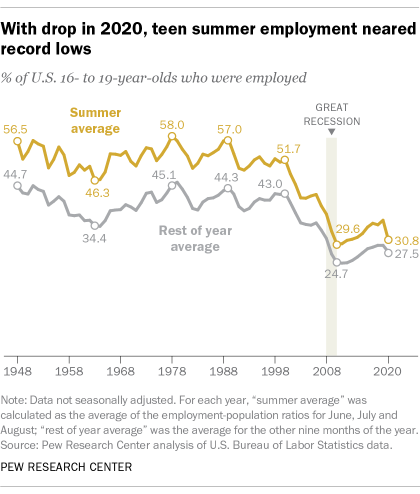

During the pandemic summer of 2020, teen summer employment in the United States plunged to its lowest level since the Great Recession, erasing a decade’s worth of slow gains, according to Pew Research Center’s latest analysis of federal employment data.

Fewer than a third (30.8%) of U.S. teens had a paying job last summer, as many of the places most likely to employ them – restaurants, shops, recreation centers, tourist attractions – were either shuttered entirely or had their operations severely curtailed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, 35.8% of teens worked over the summer.

As recently as 2000, more than half (51.7%) of U.S. teens could expect to spend at least part of their summer vacation lifeguarding, selling T-shirts, dishing up soft-serve ice cream or otherwise working for pay. But the share of teens working during the summer tumbled soon after, to 29.6% in 2010 and 2011. When teens do get summer jobs these days, they’re more likely to be busing tables or tending a grill than staffing a mall boutique or souvenir stand (despite an uptick in teen retail employment in 2020).

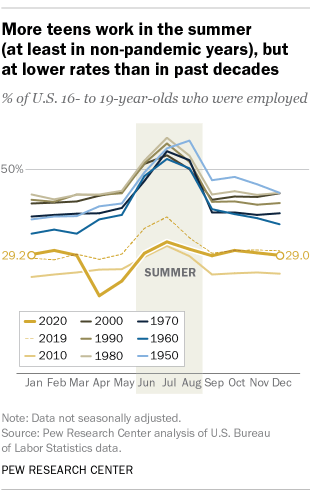

To understand what’s happened to the Great American Summer Job, Pew Research Center relied on monthly employment data gathered by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. We specifically looked at the employment rate – or, more formally, the employment-population ratio – for 16- to 19-year-olds, which the BLS has compiled since 1948. We took the average employment rate for June, July and August of each year as our measure of summer employment.

In addition, we analyzed unpublished BLS data on industry and occupational employment among 16- to 19-year-olds. Both the industry and occupational classifications schemes were revised starting with the 2020 figures; while the reclassifications on the industry side were minor and did not affect comparability, the new occupational scheme is different enough that the 2020 data can’t be compared with prior years.

We used non-seasonally adjusted data for this analysis, as teen employment normally rises sharply in the summer months and typically peaks in July.

From the late 1940s, which is as far back as the data goes, through the 1980s, teen summer employment followed a fairly regular pattern: rising during economic good times and falling during and after recessions. The teen summer employment rate fluctuated in a relatively narrow band: 46.3% (the low, in 1963) to 58% (the peak, in 1978).

That pattern began to change in the 1990s, when the teen summer employment rate didn’t experience its typical bounce-back after the 1990-91 recession. Teen summer employment fell sharply starting during the 2001 recession and dropped even more sharply during and after the 2007-09 Great Recession. The teen summer employment rate edged higher throughout the 2010s but never quite returned to pre-recession levels.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the economic restrictions imposed to combat its spread, upended the teen job market just as it did the broader job market. About 1.9 million 16- to 19-year-olds lost their jobs between February and April 2020. While there was some recovery in the ensuing months, the number of teens employed in July 2020 – what would normally be the peak month for summer jobs – fell by more than a million from July 2019.

While younger teens – 16- and 17-year-olds – are still less likely to work in the summer than their older peers, they lost jobs at a slower pace last year than did older teens (ages 18 to 19). Last summer’s average employment rate for 16- and 17-year-olds was 22.3%, down 2 percentage points from 2019. But for 18- and 19-year-olds, summer employment last year averaged 40.5%, compared with 47.8% in 2019.

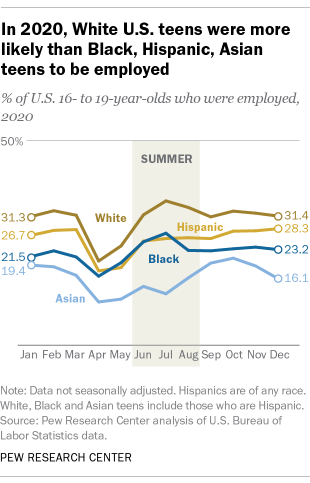

White teens are more likely to work in the summer, as well as during the rest of the year, than teens of other racial and ethnic backgrounds – a trend the pandemic did nothing to change. On average last summer, about a third (33.4%) of 16- to 19-year-old White teens were employed, compared with 25.8% of Hispanic teens, 25.1% of Black teens and 14.3% of Asian teens.

The decline in teen summer jobs is a specific instance of a broader long-term decline in overall youth employment, a trend that’s also been observed in other advanced economies.

Besides the pandemic-specific reasons why teens might not have worked last summer, researchers have suggested multiple reasons why fewer young people are working in other summers: fewer low-skill, entry-level jobs, such as sales clerks or office assistants, than in decades past; more schools ending later in June and/or restarting before Labor Day; more students enrolled in high school or college over the summer; more teens doing volunteer community service as part of their graduation requirements or to burnish their college applications; and more students taking unpaid internships, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t count as being employed.

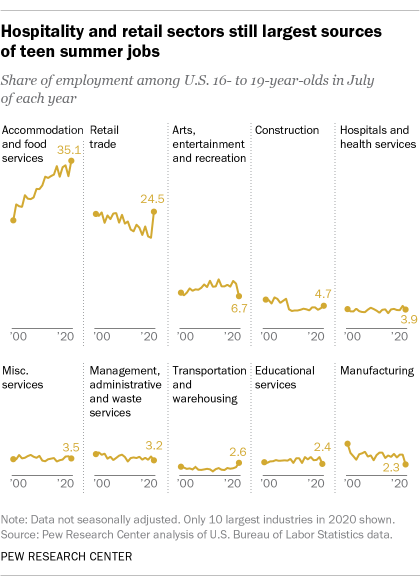

The types of summer jobs that teenagers are holding have changed over time, too – though last year’s pandemic-related shifts obscure some of the long-term trends.

More than a third (35.1%) of the estimated 5.4 million teens who were employed last July worked in the accommodation and food services industry – restaurants, hotels and the like – compared with 31.9% in July 2019 and 22.6% in July 2000, according to BLS data. Retail, after years of decline as a summertime source of teen jobs, rebounded last summer, accounting for about a quarter (24.5%) of employed teens. The retail share had fallen from 24% in 2000 to 19% in 2019.

The construction and manufacturing sectors, which together employed about 12.6% of teens in July 2000, accounted for just 7% this past July. And arts, entertainment and recreation, which had grown steadily as a summertime employer of teens since 2000 (think of all those fairs, carnivals and community pools), slumped to 6.7% of total teen summer employment in 2020, compared with 9.3% in 2019.

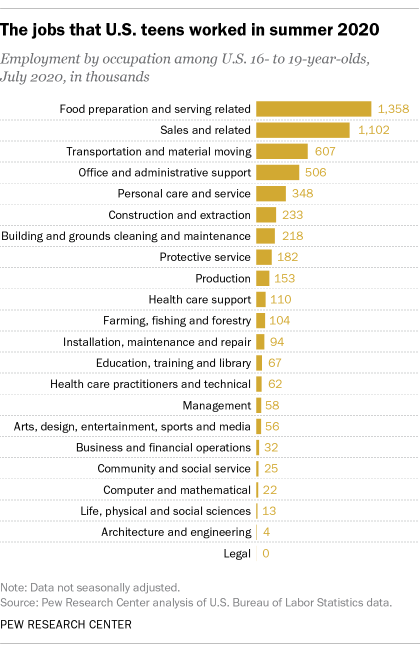

Occupational (not industry) data shows that many summer job categories continue to differ markedly by sex. Last July, for example, 27.6% of working female teens had sales jobs, compared with 12.8% of male teens. Female teens were three times as likely as males to have personal care and service jobs (9.7% vs. 3.2%) and more likely to have office and administrative support jobs (11.2% of female teens vs. 7.7% of male teens). On the other hand, male teens were far likelier than female teens to have transportation and material moving jobs (17.9% vs. 5%); construction and extraction jobs (8.8% vs. 0.1%); and installation, maintenance and repair jobs (3.4% vs. 0.1%).

As the country continues to emerge from pandemic-related shutdowns and restrictions, how do things look for teen summer employment this year?

As overall job trends indicate a strengthening economy, 32.4% of 16- to 19-year-olds, or 5.3 million teens, were employed in May 2021 (not adjusting for seasonal variations). By both measures, those are the highest May employment figures for teens since 2008. An estimated 562,000 teens were unemployed, meaning they were available and actively searching for work but hadn’t yet found any – a much stronger number than a year ago, when about 1.7 million teens were unemployed. The unemployment rate among those ages 16 to 19 was 9.5%, a vast improvement over the 30.7% rate recorded in May 2020.

That improvement, combined with reports of worker shortages as the country reopens, could portend a far better summer for teen jobs than last year.

Over the long term, though, the trend of fewer teens working over the summer seems likely to continue. Even though there were more working-age teens in May 2021 than in May 2000 (16.4 million vs. 15.9 million), far fewer of them were in the labor force: 5.9 million as of May, down from 8.1 million in 2000. And about 10.6 million teens, or nearly two-thirds of the total civilian non-institutional population ages 16 to 19, were outside the labor force entirely, compared with 7.8 million (49.1%) in May 2000.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published July 2, 2018.