Since Donald Trump was elected president in 2016 due in part to strong support from White evangelical Protestants, many observers have wondered what impact this political alliance might have on the evangelical church in the United States. Would there be an exodus from the church on the part of those who do not share their fellow evangelicals’ enthusiasm for the former president? If so, would this leave behind a smaller evangelical population, or would any such defectors be replaced by Trump-supporting converts to evangelicalism? And would White evangelicals who backed Trump in 2016 stick with him in 2020?

Contrary to what some may have expected, a new analysis of Pew Research Center survey data finds that there has been no large-scale departure from evangelicalism among White Americans. In fact, there is solid evidence that White Americans who viewed Trump favorably and did not identify as evangelicals in 2016 were much more likely than White Trump skeptics to begin identifying as born-again or evangelical Protestants by 2020.

Additionally, the surveys do not clearly show that White evangelicals who opposed Trump were significantly more likely than Trump supporters to drop the evangelical label. The data also shows that Trump’s electoral performance among White evangelicals was even stronger in 2020 than in 2016, partially due to increased support among White voters who described themselves as evangelicals throughout this period.

This Pew Research Center analysis examines American Trends Panel (ATP) respondents who participated in each of four surveys: two post-election surveys (one in 2016 and another in 2020) and two annual profile surveys (one in 2015-2016 and another in 2020). In total, 2,897 ATP panelists participated in all four of these surveys.

The ATP is an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

The 2016 post-election survey was conducted Nov. 29-Dec. 12, 2016. The 2020 post-election survey was conducted Nov. 12-17, 2020. Each survey asked respondents whom they voted for in the presidential election that had just been held. Each survey also asked respondents to rate Donald Trump on a “feeling thermometer” ranging from 0 to 100, where a rating of zero indicates the coldest, most negative possible feeling and a score of 100 indicates the warmest, most positive possible feeling. Read more about how the 2016 post-election survey was conducted and the questions it asked. Read more about how the 2020 post-election survey was conducted and the questions it asked.

ATP panelists are asked about their religious identity annually, as part of a “profile survey.” The 2016 indicators of panelists’ religious identity come from a profile survey conducted Oct. 5, 2015-April 13, 2016. The 2020 indicators of panelists’ religious identity come from a profile survey conducted Aug. 3-Sept. 20, 2020.

The questions used to categorize respondents as “born-again/evangelical Protestants” are as follows:

What is your present religion, if any? Responses include Protestant (for example, Baptist, Methodist, Non-denominational, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Episcopalian, Reformed, Church of Christ, etc.), Roman Catholic, Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or LDS), Orthodox (such as Greek, Russian, or some other Orthodox church), Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, nothing in particular.

Would you describe yourself as a born-again or evangelical Christian?

Respondents describing themselves as “Protestants” in reply to the first question and who say “yes” to the second question are defined in this report as “born-again/evangelical Protestants.”

This analysis assesses how many respondents labeled their religious identity differently in 2020 than in 2016. In doing so, it uses terms such as “defectors” to characterize those who described their religious identity differently across the two surveys. It also discusses those who “left the evangelical fold” and identifies how many people adopted the born-again/evangelical label between 2016 and 2020. Some of this religious switching undoubtedly reflects profound religious change on the part of some individuals – people who left a longtime congregation and joined a new church, for example, and others who had a moving “born-again” experience during the period covered by the study. It also may include some movement back-and-forth across religious boundaries among the “liminals,” or those who have a weak attachment to a religious identity. These individuals sometimes may describe themselves as Protestants (or Catholics or Jews or Muslims), and at other times may say they have no religion. Fortunately, assuming there is no correlation between views of Trump and “liminality,” disentangling liminality from more profound forms of religious switching (which cannot be done using this data) is not critical for assessing the link between Trump support and evangelical identity. If there is a link between views of Trump and retaining or adopting the born-again/evangelical label, it should appear over and above any movement by liminals.

For more on the liminals, see Lim, Chaeyoon, Carol Ann MacGregor and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. “Secular and Liminal: Discovering Heterogeneity Among Religious Nones.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 49, no. 4. See also Putnam, Robert D. and David E. Campbell. 2010. “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us.”

These findings come from the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), which provides a unique window into the relationship between Trump and evangelicals because it has been collecting data from a single group of respondents at various points in time since 2014. In this analysis, we examine responses from ATP members who participated in each of two surveys – one conducted right after the 2016 election, and another conducted following the 2020 election.

Here are some key findings about Trump and evangelical Protestantism in the U.S.

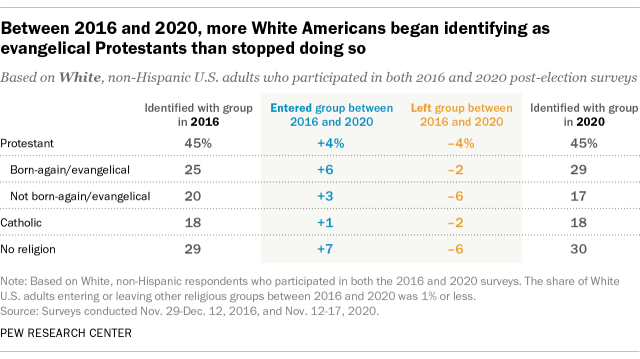

There was no mass departure of White Americans from evangelical Protestantism between 2016 and 2020. Among all White adults who participated in both the 2016 and 2020 surveys, 25% described themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants in 2016; 29% described themselves this way in 2020.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that no one stopped identifying with evangelicalism between 2016 and 2020. The survey shows that among White respondents who participated in both surveys, 2% identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016 and no longer did so by 2020. However, the 2% of White adults who stopped identifying as evangelicals during Trump’s term were more than offset by the 6% of White adults who began calling themselves born-again/evangelical Protestants between 2016 and 2020.

There were more defections during this time period among White Protestants who did not identify as born-again or evangelical in 2016. Overall, 6% of White adults described themselves as non-evangelical Protestants in 2016 but not in 2020, while 3% started identifying as such during the Trump administration.

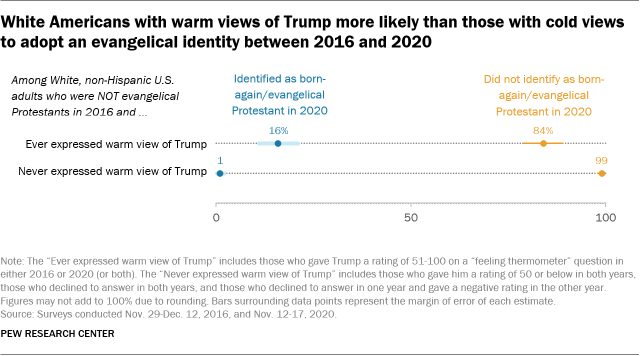

Between 2016 and 2020, White Americans with warm views toward Trump were far more likely than those with less favorable views of the former president to begin identifying as born-again/evangelical Protestants, perhaps reflecting the strong association between Trump’s political movement and the evangelical religious label.

Among White respondents (including both voters and nonvoters) who did not identify as evangelicals in 2016 and who expressed a warm view of Trump at some point during the timespan of this study, 16% began describing themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants by 2020. In stark contrast, almost no White respondents (just 1%) who expressed consistently cold or neutral views toward Trump adopted the born-again/evangelical label for themselves between 2016 and 2020.

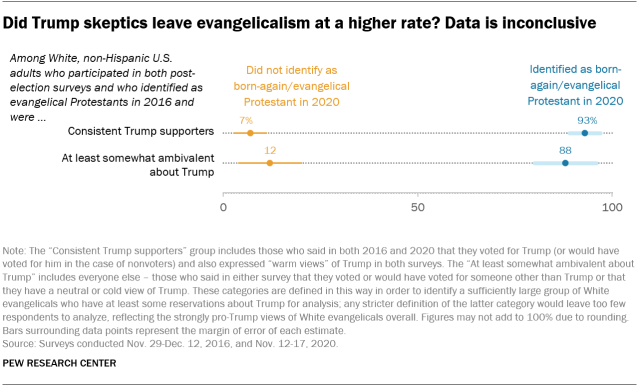

There is no clear evidence that White evangelicals who opposed Trump were more likely than Trump supporters to leave the evangelical fold. And the vast majority of White adults who identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016 still did so in 2020 – not surprising given the relatively short period of time between the two presidential elections.

Among White respondents (both voters and nonvoters) who identified as evangelical Protestants in 2016 and expressed at least some ambivalence about Trump, 88% still identified as evangelicals in 2020, while 12% no longer did so. (This group is defined as those who said they voted or would have voted for someone other than Trump in 2016 or 2020 or said they have a neutral or cold view of him at either point in time.) Among consistent Trump supporters, 93% still identified as evangelicals in 2020, while 7% no longer did. Though the 12% defection rate among Trump skeptics is nominally higher than the 7% defection rate among Trump supporters, the difference is not statistically significant given the surveys’ margins of error.

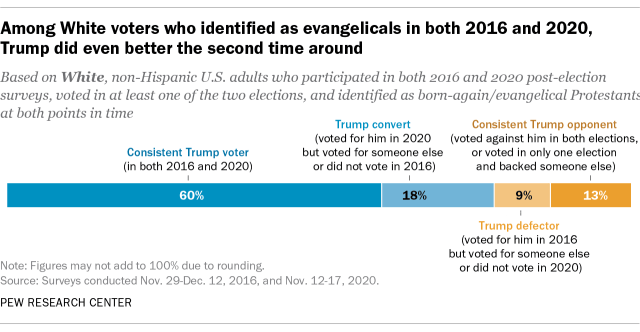

Trump garnered even more support in 2020 than in 2016 among White voters who identified as evangelical Protestants in both years and voted in at least one of the two elections. Six-in-ten in this group were consistent Trump supporters who cast ballots for him in both 2016 and 2020, and an additional 18% were Trump converts – they backed him in 2020 after voting for another candidate or not voting at all in the 2016 general election. In total, 78% of White voters who identified as evangelicals at both points in time voted for Trump in 2020.

By contrast, 9% of voters in this group were Trump defectors who backed someone else or did not vote in 2020 after voting for Trump in 2016. The remaining 13% did not vote for Trump in either election.

Trump’s improved performance among this group is one key reason that his overall vote share among White evangelical voters – including those who’d been evangelical all along and those who began identifying as evangelical between 2016 and 2020 – ticked up from 77% in 2016 to 84% in 2020.

Other factors also could have contributed to Trump’s improved performance among White evangelicals as a whole. For example, he could have obtained high levels of support from new White evangelicals who joined the ranks of voters between 2016 and 2020. His share of the evangelical vote could also have been boosted if former evangelical voters (i.e., those who were evangelical voters in 2016, but not in 2020) were disproportionately composed of Trump opponents. Unfortunately, the surveys included too few interviews with either new White evangelical voters (those who adopted the evangelical label for themselves between 2016 and 2020) or former White evangelical voters (those who abandoned the evangelical label by 2020) to be able to provide firm estimates of their views.

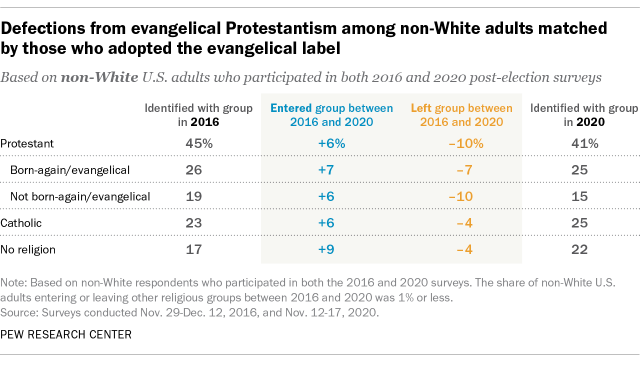

The share of non-White U.S. adults who abandoned the born-again/evangelical label in recent years is offset by the share who adopted it. Among non-White respondents who participated in both the 2016 and 2020 surveys, 26% identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016, and 25% identified this way in 2020. Of course, some did drop the born-again/evangelical label during Trump’s term (7% of all non-White respondents), but they were offset by an equal share (7%) who adopted the born-again/evangelical label during the same period.

The surveys did not include enough interviews with Black, Hispanic and other non-White Americans to permit analyzing them separately, or to discern whether Trump opponents were more likely than Trump supporters to drop the evangelical label. This reflects the prevailing opposition to Trump in this group: In the 2020 survey, for example, just 30% of non-White voters who identify as born-again or evangelical Protestants (including just 12% of Black evangelical voters) reported casting a ballot for Trump.