Many major religions have clear teachings about good and evil in the world. For example, the Abrahamic traditions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – use concepts such as God and the devil or heaven and hell to illustrate this dichotomy.

It may be somewhat unsurprising, then, that highly religious Americans are much more likely to see society in those terms, while nonreligious people tend to see more ambiguity, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

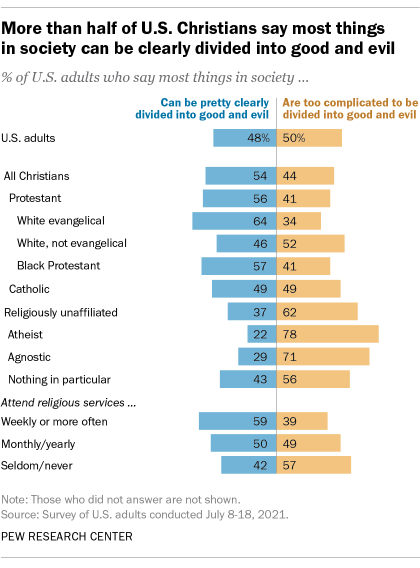

Overall, about half of U.S. adults (48%) say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil, while the other half (50%) say that most things in society are too complicated to be categorized this way. However, there are stark differences in opinion based on respondents’ religious affiliation and how religious they are.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand the public’s views on good and evil in society. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,221 U.S. adults in July 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

For example, U.S. Christians are much more likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil (54% vs. 37%). Nearly two-thirds of White evangelical Protestants (64%) say this, as do 57% of Black Protestants. Members of these two groups also attend religious services and pray at higher rates than other U.S. adults.

By comparison, only around half of U.S. Catholics (49%) and White Protestants who do not identify as evangelical (47%) say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil.

Among those who identify their religion as “nothing in particular,” 43% say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil. But far fewer atheists (22%) and agnostics (29%) say the same. Combined, these three groups make up the nation’s religiously unaffiliated population, also known as religious “nones”; overall, a majority of these unaffiliated Americans (62%) say most things in society are too complicated to be divided into good and evil.

Due to sample size limitations, this analysis does not include some smaller religious groups who were asked this question, such as Jewish and Muslim Americans.

Differences over whether most things in society can be divided into good and evil also are apparent when looking at various measures of religious observance. Highly religious Americans – regardless of their religious affiliation – are more likely to see society in terms of good and evil. For instance, U.S. adults who say they attend religious services at least once a week are more likely than those who seldom or never attend services to give this response (59% vs. 42%). And there are similar patterns when it comes to the self-professed importance of religion in people’s lives and their prayer habits.

Previous Pew Research Center surveys have found that many highly religious people look to God as a marker of good and evil and say that it is necessary to believe in God in order to be a moral person.

Even within religious groups, Democrats and Republicans have different attitudes about good and evil

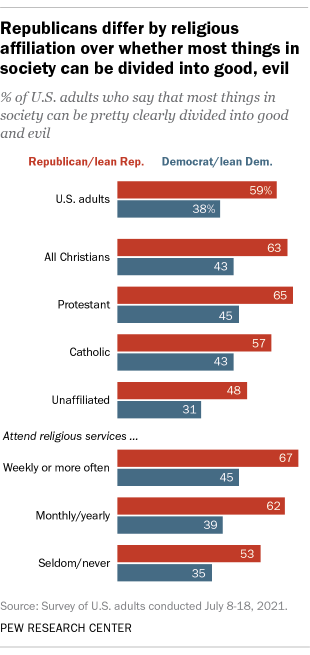

Views about good and evil also vary by political party. Roughly six-in-ten Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party (59%) say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil, compared with 38% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Religious groups differ from one another in their political makeup. For example, White evangelical Protestants are more likely to be Republicans, while atheists and agnostics tend to align with the Democratic Party. Still, party identification does not fully explain the religious differences described in this analysis; within both parties, there are large differences across religious groups.

For instance, Republican Christians are more likely than Republican “nones” to say that most things in society can be clearly divided into good and evil (63% vs. 48%). Similarly, Democratic Christians are more likely than Democratic “nones” to give that response (43% vs. 31%).

The reverse pattern is also true: Religious differences do not entirely account for the political gaps in views of good and evil. This is evidenced by the fact that Catholic Republicans are more likely than Catholic Democrats to see clear distinctions between good and evil (57% vs. 43%), a pattern that also holds true among Protestants.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.