Depending on where in the United States you live and whom you work for, Columbus Day may be a day off with pay, another holiday entirely, or no different from any other Monday.

Columbus Day continues to be one of the more contentious of U.S. public holidays. Although the federal holiday on the second Monday in October is still officially called Columbus Day, President Biden has for the past two years also proclaimed it Indigenous Peoples’ Day, as have dozens of state and localities around the country. (Such proclamations, however, typically don’t make permanent changes in the law, and at least some appear not to have been reissued.)

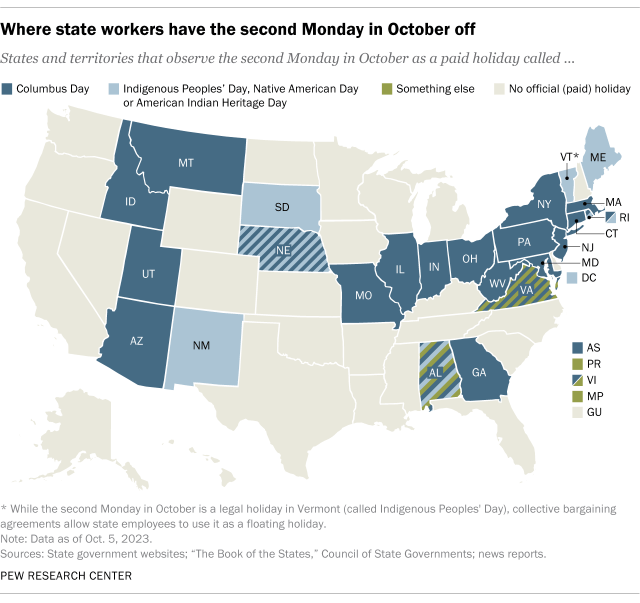

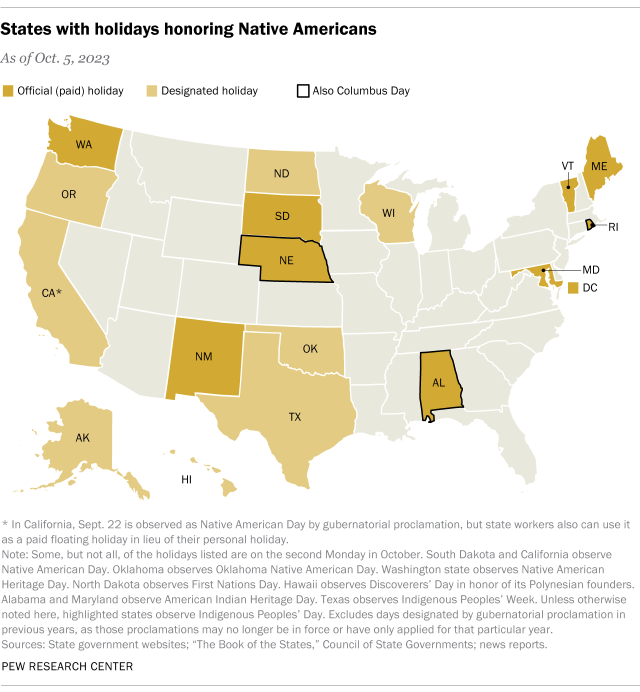

Our latest update on the status of Columbus Day focuses on states and territories that observe it (or one of its substitutes) as an official public holiday – meaning that state offices are closed and state workers get a paid day off. Several other states have designated the second Monday in October as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, or some other name honoring Native Americans, without making it an official state holiday.

In most cases, our sources for this post were state administrative, personnel and human resources websites that list official state holidays, along with official compilations of state statutes. When those weren’t available or didn’t have the information we sought, we consulted other agency websites, news media reports and reputable unofficial sources such as local chambers of commerce.

For information about which states observed Columbus Day in previous years and when they switched or dropped it, we turned to “The Book of the States,” published by the Council of State Governments, along with news media accounts, historical essays and other sources.

Columbus Day, the second Monday in October, is one of the most inconsistently celebrated U.S. holidays. It’s one of 11 official federal holidays, which means federal workers get a paid day off and there’s no mail delivery. Because federal offices will be closed, so will most banks and the bond markets that trade in U.S. government debt. The stock markets will remain open, however, as will most retailers and other businesses.

Beyond that, Columbus Day seems to be fading as a widely observed holiday, having come under fire in recent decades from Native American advocates and others, who’ve argued that Christopher Columbus isn’t an appropriate person to celebrate.

Based on our review of state statutes, human resources websites and other sources, only 16 states and the territory of American Samoa still observe the second Monday in October as an official public holiday exclusively called Columbus Day. (“Official public holiday” typically means government offices are closed and state workers, except those in essential positions, have a paid day off.) In four states, two territories and Washington, D.C., the day is an official public holiday but goes by a different name. Four other states and the U.S. Virgin Islands mark the day as both Columbus Day and something else. And in 26 states and the territory of Guam, the second Monday in October is pretty much like any other workday.

Even two decades ago, before much of the recent reevaluation of the Italian explorer, only 25 states and the District of Columbia observed Columbus Day as a public holiday, according to the Council of State Governments’ comprehensive “Book of the States.”

Since then, several states have moved away from Columbus Day. California and Delaware dropped the holiday entirely in 2009, the latter swapping in a floating holiday for state workers. Maine, New Mexico, Vermont and D.C. all renamed the day Indigenous Peoples’ Day in 2019, while retaining it as an official holiday. (While the day is a legal holiday in Vermont, collective bargaining agreements allow state employees to use it as a floating holiday.)

In Hawaii, the day is known as Discoverers’ Day, though it isn’t – and by law can’t be – an official state holiday. And Puerto Rico marks the second Monday in October as Día de la Raza (Descubrimiento de América), a celebration of Latin American peoples and cultures. (The commonwealth also commemorates Día del Descubrimiento de Puerto Rico on Nov. 19 to mark Columbus’ arrival in Puerto Rico.)

Colorado – the first state to designate Columbus Day as a state holiday more than 100 years ago – replaced it in 2020 with a new state holiday (on the first Monday in October) honoring Frances Xavier Cabrini, a Catholic nun and Italian immigrant who founded dozens of schools, hospitals and orphanages to serve poor immigrants and was canonized a saint in 1946.

Since 1990, South Dakota has observed Native Americans’ Day as an official state holiday on the second Monday in October. Tennessee officially observes Columbus Day, but on a completely different day: The governor can (and routinely does) move the observance to the Friday after Thanksgiving, to facilitate a four-day weekend. The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands began substituting Commonwealth Cultural Day for Columbus Day in 2006.

Even places with official Columbus Day holidays sometimes give them alternative monikers. Nebraska and Rhode Island, for instance, have designated the second Monday in October to be Indigenous Peoples’ Day as well as Columbus Day.

The U.S. Virgin Islands formally observes Columbus Day but puts much more emphasis on Virgin Islands-Puerto Rico Friendship Day, which just happens to fall on the same day. In Alabama, the second Monday in October is simultaneously Columbus Day, American Indian Heritage Day (since 2000) and Fraternal Day, a day honoring Freemasons, Rotarians, Elks and other social and service clubs. Columbus Day doubles as Yorktown Victory Day in Virginia.

Even Columbus, Ohio, no longer observes its namesake’s holiday, having renamed it Indigenous Peoples’ Day in 2020. But Columbus, Georgia, has retained the day’s original name.

Originally conceived as a celebration of Italian American heritage, Columbus Day was first observed as a federal holiday in 1937, largely due to lobbying by the Knights of Columbus. The holiday was moved from Oct. 12 to the second Monday in October starting in 1971.

More recently, Native American groups and other critics have advocated for changing the holiday to something else, citing Columbus’ own mistreatment of natives and his legacy of European settlement. Several states (including Alaska, Iowa, Michigan and Oregon) and dozens of cities (including Seattle, San Antonio, Houston and Boston) have recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead, though not always enshrined in law or as an official, permanent public holiday.

California, for example, is among the 26 states that don’t have an official public holiday on the second Monday in October. But in the past, it has designated the day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day by gubernatorial proclamation. California law also designates the fourth Friday in September as Native American Day, which state employees may take in lieu of their annual personal holiday.

In Texas, the legislature in 2021 declared the second week of October as Indigenous Peoples’ Week. And in Oklahoma – a state with 39 recognized Native American tribes and where, according to the latest Census estimates, about one-in-seven residents identify as American Indian – state law directs the governor to proclaim an official day for every tribe in the state, on a date of each tribe’s choosing.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on Oct. 14, 2013.