What defines a family? The portrait of the American family circa 2010 starts where it always has—with mom, pop and the kids. But the family album now also includes other ensembles. For example, most Americans say a single parent raising a child is a family. They also say that parents don’t have to be married to be a family, nor do they have to be of the opposite sex.

In an effort to explore these definitional boundaries, the Pew Research survey asked respondents whether they considered each of the following seven living arrangements to be a family: a married couple raising one or more children; a married couple with no children; a single parent raising at least one child; an unmarried man and woman raising at least one child; a gay or lesbian couple with children; a same-sex couple without children; and an unmarried, childless man and woman who are living together.

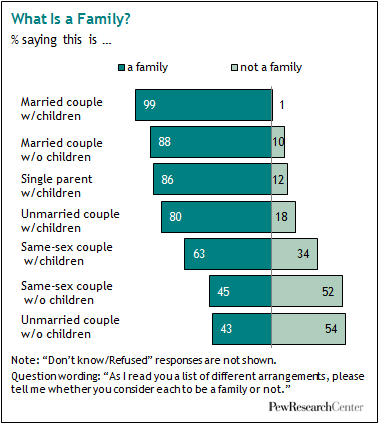

Virtually all respondents (99%) agree that a married couple with children fit in their definition of family.

But other living arrangements have joined the traditional family unit in the public’s conception of a family. Nearly nine-in-ten Americans (88%) say a childless married couple is a family, and nearly as many say a single parent raising at least one child (86%) and an unmarried couple with children (80%) are families. A smaller majority say a gay or lesbian couple raising at least one child is a family (63%).

The public is less willing to say same-sex and unmarried heterosexual couples without children are full-fledged families. More than four-in-ten say a gay or lesbian couple living together without children is a family (45%), while a larger proportion (52%) disagrees. The public also tilts negative when asked if a man and woman who live together but don’t have children are a “family”: 43% say they are, but 54% say they are not.

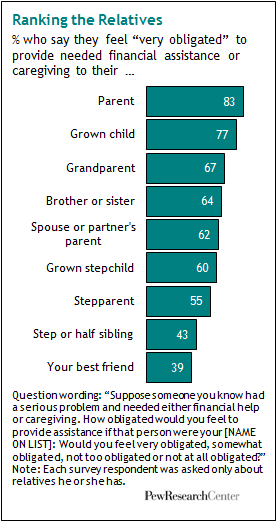

The survey questionnaire explored the boundaries of family in another way—by asking people how obligated they would feel to help out various relatives in times of need. The responses line up in a predictable hierarchy: People feel much more obligated to help out (with financial assistance or caregiving) a parent or a grown child than a stepparent or half sibling. But despite these differences, the sense of obligation flows more readily to each of the relatives on the list than it does to “your best friend”—suggesting that even as family forms become more varied, family connections bind in ways that friendships do not.

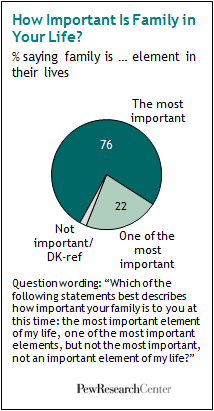

Responses to other survey questions also attest to the overarching importance of family. Three-quarters of all adults say their family is the “most important” element in their lives, and an equal proportion say they are very satisfied with their home lives.

Nearly half of the public say their family life has turned out pretty much like they expected it would be. But almost as many (47%) say their home life has taken an unexpected turn. For some, this means a family life that is even better than they imagined. But for a larger share, their expectations have been undermined by divorce, the premature death of a spouse or other blows.

The remainder of this section will examine these questions in greater detail. Additional questions that measure other views on family life also will be reported and analyzed by family type and other relevant demographic characteristics.

Demographic Differences in Definition of Family

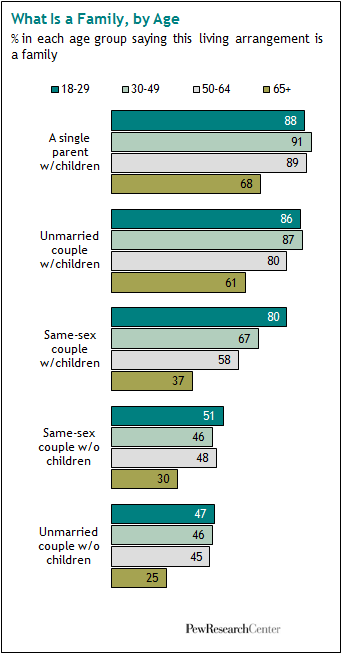

Virtually every major demographic group agrees that a married couple with or without children falls within their definition of family. Demographic differences, particularly by age, begin to emerge when respondents are asked whether a single parent living with at least one child is a family. Even larger gaps open up when the subject turns to other less common living arrangements.

Different generations define families differently. The generation of Americans who came of age in the early 1950s watching Ozzie and Harriet on their black-and-white televisions—adults 65 and older—are consistently more likely to say that non-traditional living arrangements fall short of meeting their definition of family. Even those in the next-oldest generation of adults—those between the ages of 50 and 64, the bulk of the Baby Boom generation—are significantly more likely than this older group to see these arrangements as a family.

The difference between older adults and every other generation is most clearly seen when respondents are asked if a single parent raising a child is a family. Majorities of all age groups say this arrangement is a family. But while two-thirds of adults 65 and older say this arrangement is a family (68%), this share is less that the 88% of adults ages 18 to 29 and the 91% of adults ages 30 to 49 who feel the same way.

Double-digit differences between the views of older Americans and other age groups emerge on every other non-traditional family arrangement tested. The gap swells to 20 percentage points or more when respondents are asked whether same-sex couples raising at least one child are families.

Fully eight-in-ten adults younger than 30 say a same-sex couple with children is a family, more than double the proportion of those 65 and older who share this view (80% vs. 37%). But views on this living arrangement also vary significantly between the other generations. Among those ages 30 to 49, two-thirds (67%) see a same-sex couple with children as a family, compared with 58% of all 50- to 64-year-olds.

Demographic Differences on Other New Family Arrangements

Differences between other demographic groups also emerge when the focus turns to the three living arrangements tested in the survey that are the least likely to be considered a family: same-sex couples with and without children, and unmarried heterosexual couples with no children. These differences include:

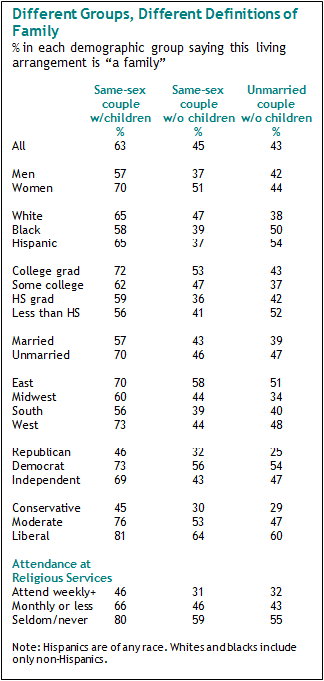

Gender Men are significantly less likely than women to say same-sex living arrangements are families. Fewer than six-in-ten men (57%) but 70% of women say a gay or lesbian couple with children is a family. That gender gap opens to 14 percentage points when men and women are asked about same-sex couples without children (37% of men but 51% of women consider them to be families). The sexes do agree about unmarried couples without kids: 42% of men and 44% of women say they are families.

Race Blacks are less likely than whites or Hispanics to say that same-sex couples with children are families (58% for blacks vs. 65% for whites and Hispanics). At the same time, whites are the least likely of the three groups to say an unmarried couple with no children is a family (38% vs. 50% for blacks and 54% for Hispanics).

Education More educated adults are somewhat more accepting of same-sex couples as families than are those with less education. But those who have not earned a high school diploma—a group disproportionately composed of minorities—are more likely than college graduates to say an unmarried couple with no children is a family (52% vs. 43%).

Marital Status Married adults are significantly less likely than unmarried adults to say that a same-sex couple with children is a family (57% vs. 70%). They also disagree about whether a man and woman who live together and don’t have children is a family (39% of all married people say yes, compared with 47% of all unmarried adults). But the two groups are equally divided when it comes to same-sex couples without children (43% of married people and 46% of those who are unmarried say they are a family).

Region Americans living in different regions of the country differ on what is a family. In the South, significantly fewer residents say same-sex couples with or without children are families. Still, a majority of residents in the South (56%) say gay or lesbian couples with children are families, compared with 73% in the West, 70% in the East and 60% in the Midwest. Midwesterners are the least likely to say unmarried couples without children are families (34% vs. 40% of southerners, 48% of western residents and 51% of easterners).

Politics, Religion and Definitions of Family

Political partisanship and ideology also are strongly correlated with definitions of what is a family. Religion—or more specifically, religiosity as measured by attendance at religious services—also plays a major role in shaping definitions of family.

According to the survey, Republicans, political conservatives and adults who attend religious services at least once a week are significantly less likely than Democrats, political moderates or liberals, and the less religiously observant to view same-sex or unmarried couples as families.

Overall a majority of Democrats say each of the seven living arrangements fit their conception of a family while Republicans are more likely to say some types are not families. For example, a gap of 27 percentage points exists between the proportion of Republicans (46%) and Democrats (73%) who say a gay or lesbian couple raising at least one child is a family. Among independents, about seven-in-ten share this view. The gap is 34 points in the same direction when partisans are asked about childless same-sex couples and 29 points on unmarried couples with no children. Similarly large differences exist among political liberals, conservatives and moderates.

Even larger gaps emerge when the focus of the analysis switches to religion. More religious adults are less likely than the less observant to see each of the three non-traditional living arrangements as a family.

These differences are among the largest encountered in this survey. For example, slightly under half (46%) of adults who attend religious services at least once a week consider a same-sex couple raising a child to be a family, compared with 80% of those who seldom or never go to services.

The gap narrows when the focus turns to gay couples without children. Here about three-in-ten of the most religiously observant say this arrangement meets their definition of a family, compared with 59% of non-religious adults. A similar-sized gap emerges over unmarried couples without children (32% vs. 55%).

Smaller Political, Religious Differences in Views on Single-Parent Families

Smaller gaps arise in views about single parents raising one or more children. Political conservatives are less likely to say this arrangement is a family (80%) than are moderates or liberals (91% for liberals and 92% for moderates). However, there is virtually no difference between Republicans (88%), Democrats (87%) or independents (87%) on this question.

As with political orientation, views on whether a single parent raising a children is a family vary only slightly by religiosity. More than eight-in-ten adults who attend religious services at least once a week (82%) or monthly or less often (86%) say single-parent households are families. In contrast, nine-in-ten (92%) of those who rarely or never go to services say a single parent raising a child is a family.

Family Obligations

The biblical injunction to honor thy father and mother has not been lost on Americans. Mom and dad lead the list when respondents are asked which of eight relatives they feel they have a special obligation to help if that person needs financial assistance or caregiving. More than eight-in-ten Americans say they feel “very obligated” to help if their parents needed it. Grown children come next, with 77% feeling obligated to help them get over hard times, while smaller proportions feel a similar responsibility to assist their grandparents (67%), a sibling (64%) or the parent of a spouse or partner (62%). (No question was asked about minor children because it was assumed virtually all parents consider caring for them in times of need to be an obligation.)

Stepchildren, stepparents, and step or half siblings don’t fare quite so well. Parents are 17 percentage points more likely to feel obligated to a grown child than to a grown stepchild (77% vs. 60%). Similarly, adults are more inclined to help a parent than a stepparent (83% vs. 55%) or a brother or sister over a step or half sibling (64% vs. 43%).

Most demographic groups feel similar levels of obligation to each of the relatives tested in the survey. However, adults 65 and older are significantly less likely than other age groups to feel a special sense of obligation to provide financial assistance or caregiving to other family members, perhaps reflecting the fact they have relatively limited financial resources and, in some cases, are in diminished physical condition.

For example, half of all adults 65 and older say they feel obliged to assist a brother or sister. In contrast, three-quarters of adults younger than 30 feel they should help out a sibling, as do 67% of those ages 30 to 49 and 59% of all 50- to 64-year-olds. Similarly, these older adults feel somewhat less of a responsibility toward their grown children (68% for adults 65 and older but 81% for those ages 30 to 64).

A deeper look inside these data suggests that the typical adult feels very obligated to about three of the relatives tested in the survey. Again, this number varied little by demographic group, with the one exception: Adults 65 or older feel obligations to about one fewer relative than do other adults (median of two obligations vs. three for other age groups).

Sorry, Buddy

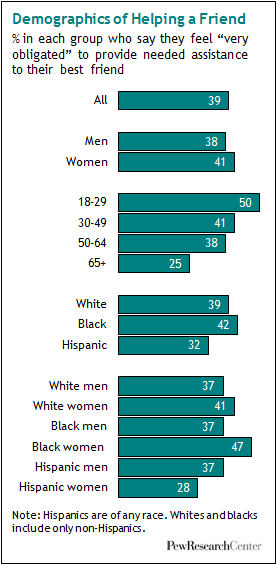

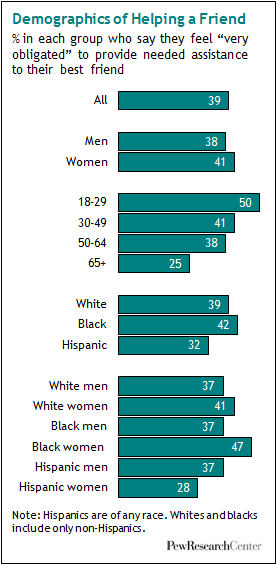

Comparatively fewer (39%) feel a compelling need to help their best friend in times of crisis. In fact, best buddies finished at the bottom of the list of types of people that respondents felt “very obligated” to help—more evidence of the value that people place on relationships.

Young people and black women are especially likely to add their best friends to the list of people they would assist financially or to whom they would provide caregiving in a crisis. Half of all adults ages 18 to 29 say they feel very obligated to help their best friends, compared with 41% of 30- to 49-year olds, 38% of 50- to 64-year-olds and 25% of those 65 and older.

Nearly half of black women (47%) say they feel compelled to help out a best friend in distress, compared with 37% of black men. Latino women are the least likely to say they would help out their best friend; less than three-in-ten (28%) would, compared with 37% of Hispanic men. Among whites, the gender differences are virtually non-existent: 37% of white men and 41% of white women feel the need to assist their best friend.

Importance of Family

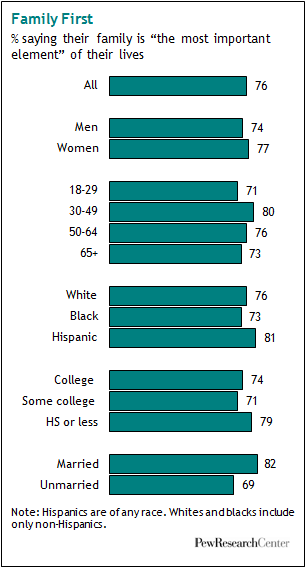

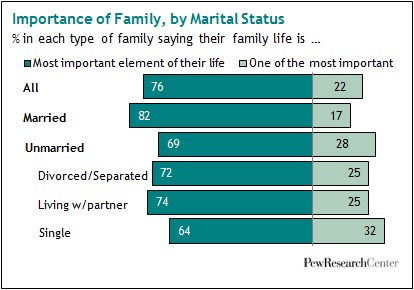

Ask Americans what is most important in their lives, and it’sclear that families come first. Fully 76% of adults say that their family is the single most important element of their lives. It is a judgment that varies only moderately across most key demographic characteristics.

Young or old; male or female; married or unmarried; black, white or Hispanic—lopsided majorities of Americans say they are committed above all to their families. While politics and religiosity divide Americans on what constitutes a family, these differences vanish when they are asked to judge the importance of family life. Virtually identical proportions of Republicans (76%) and Democrats (74%) say their family is the most important thing in their lives, as do 74% of those who attend religious services at least once a week and 73% who seldom or never go.

The few differences that do emerge are modest. Eight-in-ten adults ages 30 to 49 put a premium on their family life, compared with slightly more than seven-in-ten 18- to 29-year-olds (71%) or 73% of those 65 and older. That is hardly surprising, because it is in the decades between a person’s 20s and later middle age that families are formed and mature.

Hispanics are somewhat likelier to place more value on their family life than are blacks (81% vs. 73%). Hispanic women in particular place a premium on their family life; nearly nine-in-ten Latino women (87%), compared with 75% of Hispanic men, rate their families as most important.

Less-educated adults also put a somewhat higher value on family life than do the more educated; eight-in-ten respondents with a high school diploma or less education but 74% of adults with a college degree say their families are the most important element in their lives.

Family Types and the Importance of Family

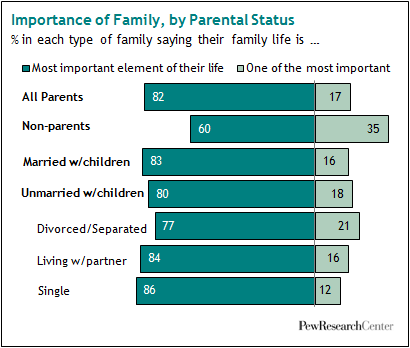

Married adults place a higher value on family life than do unmarried adults (82% versus 69%), and this holds true whether the unmarried adult is divorced (72% of this group say family is the most important element of their life); single, never married (64%) or cohabiting with a partner (74%) say family is the most important element in their lives.

Parenthood is also correlated with the value people place on family. Some 82% of all parents say family is the most important part of their lives, compared with 60% of adults who are not parents. Moreover, no matter what the family type, adults in families that include children place a higher value on family than do those in families without children.

Consider this example: Overall, unmarried adults are significantly less likely than married people to say their families are the most important thing in their lives (69% vs. 82%). But when the analysis is limited to adults with children, this large difference vanishes; 86% of single parents versus 83% of married parents say family is the most important thing in their lives. Also, the survey finds that nearly nine-in-ten (86%) single, never-married adults with children and 84% of single parents living with a partner say their family life is the most important element in their lives.

Satisfaction with Family Life

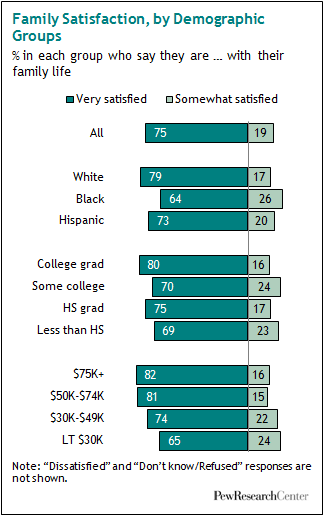

Most Americans are happy at home. Three-quarters of all adults say they are “very satisfied” with their family life, and an additional 19% say they are “somewhat satisfied” with their home lives, according to the survey.

With a few notable exceptions, these upbeat assessments of life on the home front are broadly shared across most major demographic groups. Roughly equal proportions of men (74%) and women (75%) say they are very satisfied with their family life. Three-quarters of young adults ages 18 to 29 are similarly pleased with their family life, a view shared by a similar proportion of adults 65 and older (75% and 77%, respectively).

Whites are somewhat more content with their home lives than are Hispanics (79% vs. 73% say they are “very satisfied”), and both groups express higher levels of family satisfaction than do blacks (64%).

While money might not always buy personal happiness, it may make things easier at home. More than eight-in-ten adults with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more are very satisfied with their family lives, compared with 65% of those earning less than $30,000. Similarly, those with a college degree are more satisfied than those who didn’t complete high school (80% vs. 69%).

Political partisanship and religiosity also are correlated with family satisfaction. Republicans are significantly more satisfied with their family lives than are Democrats (82% vs. 71%) or independents (74%). And adults who attend religious services at least once a week are more satisfied with their family life than are those who seldom or never attend services (79% vs. 71%).

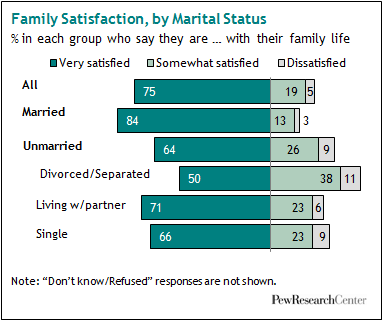

Family Type and Family Satisfaction

Married adults express far more satisfaction with their current family situation than do those who are unmarried (84% vs. 64%).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the biggest satisfaction gap by family type is between married and divorced adults: 84% of all married men and women are “very satisfied” with their family life, compared with 50% of all divorced adults, 71% of those living with a partner and 66% of singles who have never married.

Family satisfaction is somewhat greater among parents than among adults who do not have children. For example, the survey found that 85% of married adults with children are very satisfied with their family lives, compared with 81% of married couples without children.

Togetherness and the Modern Family

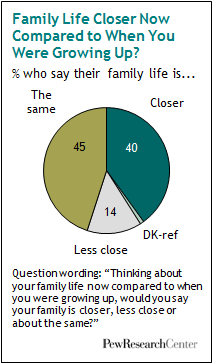

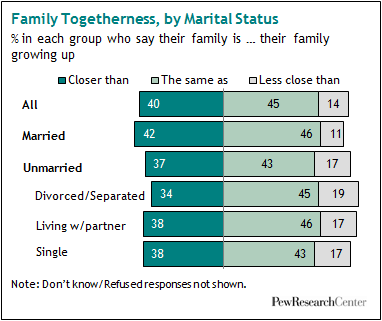

An overwhelming majority of Americans say their families are at least as close now as their families were when they were growing up. Four-in-ten (40%) say their family life is closer than it was when they were young and 45% say their families are about as close as when they were growing up. Only 14% say they are less close.

This finding isn’t likely to produce an argument around the kitchen table: These judgments vary little by gender, age, education level, income, and race or ethnicity.

The responses do vary somewhat by marital status. Married adults are significantly more likely than those who are unmarried to say their family is closer now than their family was when they were growing up (42% vs. 37%). In particular, divorced adults are significantly less likely to say their families are closer (34%).

Expectations vs. the Realities of Family Life

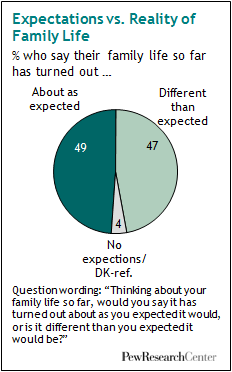

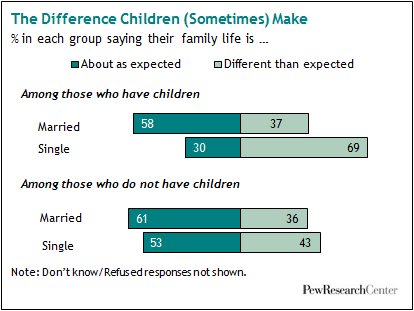

Americans divide almost equally when asked whether their family lives have so far have turned out the way they expected, views that are strongly shaped by their current marital status and, to a somewhat lesser degree, by whether or not they have children.

Nearly half (49%) of adults say their family life has turned about as they thought it would. But nearly as many (47%) say their family life has taken an unexpected turn. Only 4% say they had no expectations or did not know.

These views are highly correlated with the respondent’s current family situation, so much so that most other demographic differences largely disappear when family type and parental status are factored into the analysis.

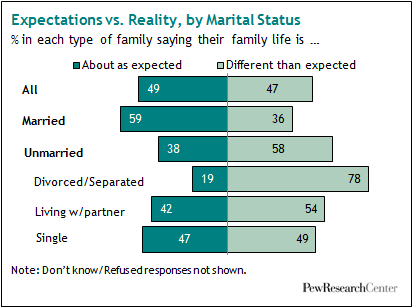

The survey findings generally suggest that most people expect to marry and anticipated that their marriage would survive until death did them part. About six-in-ten currently married adults say their family life is about as they anticipated it would be, while slightly more than a third say it is different.

But among all unmarried adults, an equally large majority (58%) say their life has not worked out as they thought it would—including 78% of those who are currently divorced.

Views are more divided among those who are currently living with a partner. About four-in-ten (42%) say they have the family life they expected, while 54% say they do not.

The presence of children in a family complicates the picture. For single, never-married adults, a child clearly changes their lives in unanticipated ways. Among those who are not married, slightly more than half (53%) say their family life is pretty much as they anticipated it would be. But for single, never-married adults with a child, only 30% say their family life is what they expected it would be, and 69% say it is not.

In contrast, children appear to make little difference for married couples: 58% with children say their family life is pretty much as they expected it to be, an assessment shared by 61% who do not have children.

How old you are or, more precisely, at what stage of life you find yourself, also plays a major role in shaping judgments about how your life has unfolded.

Overall, views on whether an individual’s family life is going as expected vary little by age. About half of every age group say their family life has turned out pretty much as they had expected.

But this consistent picture changes when age and family type are analyzed together. Consider younger and older single people who have never been married. Overall, more than four-in-ten (45%) of this group say that their lives have turned out as expected. But the share rises to 49% among never-married singles younger than 40 and drops to 34% among those 40 and older.

A similar, though smaller, age pattern emerges among parents and adults who don’t have children. More than half (54%) of adults younger than 40 without children say their life has turned out about as expected, compared with 48% of those 40 and older.

Dissecting “Difference”

Respondents who said their life was different were asked in an open-ended follow-up question to explain in their own words how it did not match their expectations. These verbatim statements were then classified into three groups: those that indicate the respondents’ family life has exceeded their expectations; those that indicate their family life has not measured up to what they thought it would be; and those that are neutral or ambiguous.

Roughly one-in-ten say their family life is better than expected.23 Some respondents seemed almost overjoyed by the way their family lives have unfolded. “Never thought I would be a full-time mom and I love it,” one 25-year-old volunteered. Most were less specific, saying their lives had “exceeded expectations” or “it’s great!” while 17 respondents responded with a single word: “better.”

About a third say their family life had fallen short of their expectations. Some respondents described heart-wrenching disruptions in their family life; roughly a third of these statements testified to the devastating impact of divorce, while others noted the painful changes that came with the early death of a spouse or child.

“I thought I would be married with kids. Now I’m divorced with no kids,” said a 39-year-old woman. “I lost three children, and that changed our whole life,” said a 49-year-old married woman.

[My]

Some reflect the disappointments that sometimes come with children. “My one son has a child and isn’t married to the lady he had it with. My daughter is divorced. My other son doesn’t have any children at all,” said a 71-year-old widowed man.

The remaining responses are neutral or are difficult to classify. Many unmarried or childless men and women simply said they expected to be married or have children, statements that could reflect current family status and not necessarily feelings of regret or anxiety.

And others marveled at the surprises life has brought them. “I never expected to have stepchildren,” said one 69-year-old married woman. “Everything is a surprise; life takes you many places,” said a 29-year-old married woman. “Not unhappy but just different” is the way a 47-year-old divorced woman summed it up.

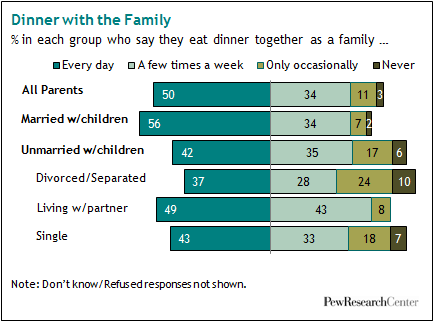

Dinnertime Is Family Time—Especially at Thanksgiving

Parents and children may be busier than ever, but they still make time to gather for a family dinner at least a few times a week. For half of all families with children younger than 18, the family dinner is a daily ritual. An additional 34% say their families eat together “a few times a week.” Only about one-in-seven (14%) say they rarely or never share a meal with their children.

Married parents with children are the most likley to say they eat together as a family every day. In contrast, slightly less than four-in-ten divorced parents (37%) and a slightly larger share of single parents (43%) have dinner with their children as often.

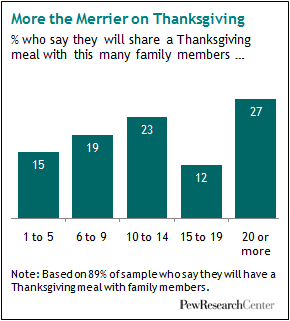

Many dinner tables are going to be crowded with relatives this Thanksgiving, the survey suggests. About nine-in-ten adults (89%) say they will be having a Thanksgiving meal with members of their family—and not just one or two.

Among those who will be sharing a drumstick with family, more than six-in-ten (62%) say that ten or more relatives will be at that Thanksgiving meal—and a quarter (27%) say there will be 20 or more. Overall, the typical host will be setting places for 12 family members, according to the survey.