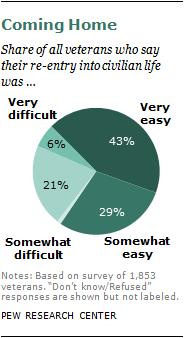

Military service is difficult, demanding and dangerous. But returning to civilian life also poses challenges for the men and women who have served in the armed forces, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey of 1,853 veterans. While more than seven-in-ten veterans (72%) report they had an easy time readjusting to civilian life, 27% say re-entry was difficult for them—a proportion that swells to 44% among veterans who served in the ten years since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Why do some veterans have a hard time readjusting to civilian life while others make the transition with little or no difficulty? To answer that question, Pew researchers analyzed the attitudes, experiences and demographic characteristic of veterans to identify the factors that independently predict whether a service member will have an easy or difficult re-entry experience.

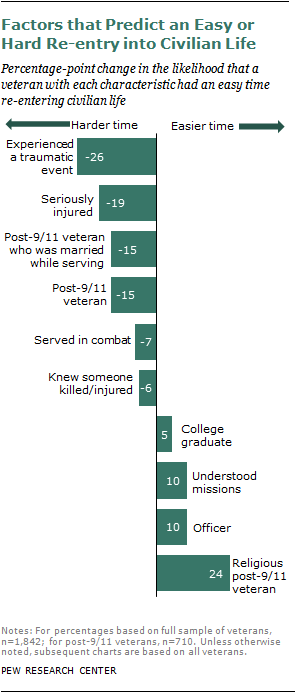

Using a statistical technique known as logistic regression, the analysis examined the impact on re-entry of 18 demographic and attitudinal variables. Four variables were found to significantly increase the likelihood that a veteran would have an easier time readjusting to civilian life and six factors predicted a more difficult re-entry experience.

According to the study, veterans who were commissioned officers and those who had graduated from college are more likely to have an easy time readjusting to their post-military life than enlisted personnel and those who are high school graduates.1 Veterans who say they had a clear understanding of their missions while serving also experienced fewer difficulties transitioning into civilian life than those who did not fully understand their duties or assignments.

In contrast, veterans who say they had an emotionally traumatic experience while serving or had suffered a serious service-related injury were significantly more likely to report problems with re-entry, when other factors are held constant.

The lingering consequences of a psychological trauma are particularly striking: The probabilities of an easy re-entry drop from 82% for those who did not experience a traumatic event to 56% for those who did, a 26 percentage point decline and the largest change—positive or negative—recorded in this study.2

In addition, those who served in a combat zone and those who knew someone who was killed or injured also faced steeper odds of an easy re-entry. Veterans who served in the post-9/11 period also report more difficulties returning to civilian life than those who served in Vietnam or the Korean War/World War II era, or in periods between major conflicts.

Two other factors significantly shaped the re-entry experiences of post-9/11 veterans but appear to have had little impact on those who served in previous eras. Post-9/11 veterans who were married while they served had a significantly more difficult time readjusting than did married veterans of past eras or single people regardless of when they served.

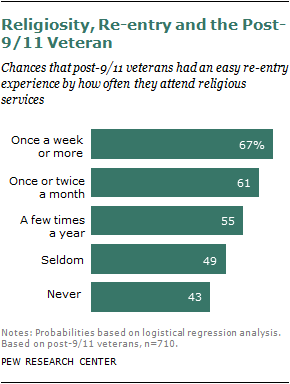

At the same time, higher levels of religious belief, as measured by frequent attendance at religious services, dramatically increases the odds that a post-9/11 veteran will have an easier time readjusting to civilian life. According to the analysis, a recent veteran who attends religious services at least once a week has a 67 percent chance of having an easy re-entry experience. Among post-9/11 veterans who never attend services, the probability drops to 43%.3 Among veterans of other eras, current attendance at religious services is not correlated with ease of re-entry.4

Eight other variables tested in the model proved to be poor predictors of how easily a veteran made the transition from military to civilian life. They are race and ethnicity (separate variables tested the effect of being white, black, Hispanic or some other race); age at time of discharge; whether the veteran had children younger than 18 while serving; how long the veteran was in the military; and how many times the veteran had been deployed.

Predicting the Ease of Re-entry

This analysis employs a statistical technique known as logistic regression to measure the effect of any given variable on the likelihood that a veteran had an easy or difficult time re-entering civilian life while controlling for the effects of all other variables.

To identify the factors that best predicted an easy re-entry, eighteen independent variables were included in the regression model. The variables were chosen based on their predictive power in previous research. The demographics were: veteran’s age at discharge; how long the individual served; the veteran’s education, race and ethnicity (tested as four separate variables: white, black, Hispanic or some other race); whether the veteran was married or had young children while in the service; highest rank attained; and era in which the veteran served. Other variables tested the impact of specific experiences on re-entry: whether the veteran had been seriously injured while serving; experienced a traumatic or emotionally distressing event; served in a combat or war zone; or served with someone who had been killed or injured. A question that asked veterans whether they understood most or all of the missions in which they participated also was included.

Of the 18 variables in the model, ten turn out to be significant predictors of a veteran’s re-entry experience. Four were positively associated with re-entry: being an officer; having a consistently clear understanding of the missions while in the service; being a college graduate; and, for post-9/11 veterans but not for those of other eras, attending religious services frequently. Six variables were associated with a diminished probability that a veteran had an easy re-entry. They were: having a traumatic experience; being seriously injured; serving in the post-9/11 era; serving in a combat zone; serving with someone who was killed or injured; and, for post-9/11 veterans but not for those of other eras, being married while in the service.

Factors that Make Readjustment Harder

Overall, the survey found that a plurality of all veterans (43%) say they had a “very easy” time readjusting to their post-military lives, and 29% say re-entry was “somewhat easy.” But an additional 21% say they had a “somewhat difficult” time, and 6% had major problems integrating back into civilian life.

Among the 18 variables tested, veterans who experienced emotional or physical trauma while serving are at the greatest risk of having difficulties readjusting to civilian life. According to the analysis, having an emotionally distressing experience reduces the chances that a veteran would have a relatively easy re-entry by 26 percentage points compared with a veteran who did not have an emotionally distressing experience. Similarly, suffering a serious injury while serving reduces the probability of an easy re-entry by 19 percentage points, from 77% to 58%.

Overall, the survey found that serious injuries and exposure to emotionally traumatic events are relatively common in the military. Nearly a third (32%) of all veterans say they had a military-related experience while serving that they found to be “emotionally traumatic or distressing”—a proportion that increases to 43% among those who served since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. About one-in-ten veterans (10%) suffered a serious injury; of those who served in the post-9/11 era, 16% suffered a serious injury, in part because service members with serious injuries are more likely to survive today than in previous wars, when those with serious injuries died.

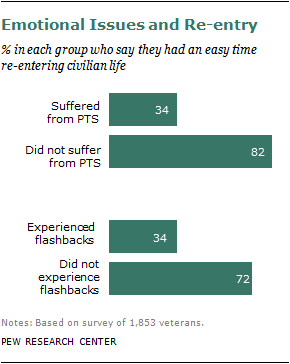

The survey also pinpoints some of the specific problems faced by returning service members who suffered service-related emotional trauma or serious injury. More than half (56%) of all veterans who experienced a traumatic event say they have had flashbacks or repeated distressing memories of the experience, and nearly half (46%) say they have suffered from post-traumatic stress.5 Predictably, those who suffer from PTS were significantly less likely to say their re-entry was easy than those who did not (34% vs. 82%).

According to the model, serving in a combat zone reduces the chances that a veteran will have an easier time readjusting to civilian life (78% for those who did not serve in a combat zone to slightly more than 71% for those who did). Knowing someone who was killed or injured also lessens the probability that a veteran will have an easy re-entry by six percentage points (73% vs. 79%).

Service Era and Re-entry

Many veterans who served after Sept. 11, 2001, have experienced difficulties readjusting to civilian life. The model predicts that a veteran who served in the post-9/11 era is 15 percentage points less likely than veterans of other eras to have an easy time readjusting to life after the military (62% vs. 77%).

A word of caution about comparing re-entry experiences between service eras. Those in the post-9/11 era were interviewed relatively soon after they left the military, and their views could reflect the immediacy of their experience and could change over time. For earlier generations of veterans, their views could have changed from what their views were at a similar point in their post-military lives.

Also, the overall view of veterans of earlier eras could change as members of this generation die and the composition of the cohort becomes different. As a consequence, these results are best interpreted as the views and experiences of current living veterans from each era, and not necessarily the views each generation held in the years immediately after leaving the service.

Marriage and Re-entry

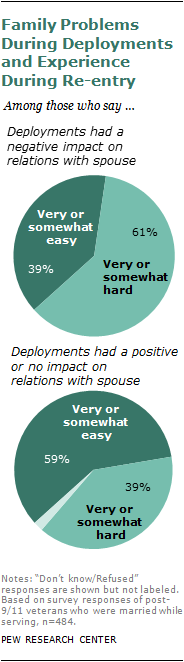

The analysis produced a surprise. Post-9/11 veterans who were married while they were in the service also had a more difficult time readjusting to life after the military. Overall, being married while serving reduces the chances of an easy re-entry from 63% to 48%.

At first glance, this finding seems counterintuitive. Shouldn’t a spouse be a source of comfort and support for a discharged veteran? Other studies of the general population have shown that marriage is associated with a number of benefits, including better health and higher overall satisfaction with life.6

In fact, the answer to another survey question points to a likely explanation. Post-9/11 veterans who were married while in the service were asked what impact deployments had on their relationship with their spouse. Nearly half (48%) say the impact was negative, and this group is significantly more likely than other veterans to have had family problems after they were discharged (77% vs. 34%) and to say they had a difficult re-entry.

Among those married while they were in the service, about six-in-ten (61%) post-9/11 veterans who had experienced marital problems while deployed also had a difficult re-entry. In contrast, about four-in-ten veterans (39%) who reported that deployments had a positive or no impact on their marriage say they had problems re-entering civilian life—virtually identical to the proportion of then-single post-9/11 veterans (37%) who experienced difficulties re-entering civilian life.

Taken together, these findings underscore the strain that deployments put on a marriage before a married veteran is discharged and after the veteran leaves the service to rejoin his or her family.

Factors that Improve the Chances of an Easy Re-entry

Three variables tested in the model—rank at the time of discharge, how well the mission was understood and education level—emerged as statistically significant predictors of an easy re-entry experience for all veterans. A fourth variable, religiosity as measured by service attendance, is a powerful predictor of an easier re-entry experience for post-9/11 veterans but not for those who served in earlier eras.

The model predicts that commissioned officers are 10 percentage points more likely than enlisted personnel to experience few if any difficulties readjusting to life at home (85% vs. 74%),7 when all other factors are held constant. Veterans who say they clearly understood their missions while serving also were more likely than those who did not to have an easier re-entry (77% vs. 67%).8

College-educated veterans also are predicted to have a somewhat easier time readjusting to life after the military than those with only a high school diploma. According to the analysis, a veteran with a college degree is five percentage points more likely than a high school graduate to have an easy time with re-entry (78% vs. 73%).

Again, a word of caution is in order. Veterans in the survey were asked how many years of school they have attended. Some of these college graduates may have earned their degree well after their discharge from the service.

Religiosity and Re-entry

Among the larger factors influencing the re-entry experience of post-9/11 veterans is religious faith, as measured by how often a recent veteran attends religious services. Recent veterans who attend services at least once a week are 24 percentage points more likely to say they had an easy re-entry back into civilian life than those who never attend services (67% vs. 43%). This finding is consistent with other studies of the general population that suggest religious belief is correlated with a number of positive outcomes, including better physical and emotional health, and happier and more satisfying personal relationships.9

The impact of religious observance vanishes if the sample is based only on those who completed their service before Sept. 11, 2001. In fact, there is barely a one percentage point difference in the probability of an easy re-entry between older veterans who currently attend religious services and those who never do.

As noted earlier, one reason for the absence of an impact may be related to the question measuring current attendance at religious services. This measure of attendance may be a good proxy for the religious convictions of more recent veterans. But it may be a poor estimate of how religious older veterans were immediately after they were discharged from the service. Over the years the religious belief of these older veterans may have changed, obscuring the impact of religious conviction on their re-entry experience.