As Republicans gather for their national convention in Tampa to nominate a presidential candidate known, in part, as a wealthy businessman, a new nationwide Pew Research Center survey finds that many Americans believe the rich are different than other people. They are viewed as more intelligent and more hardworking but also greedier and less honest.

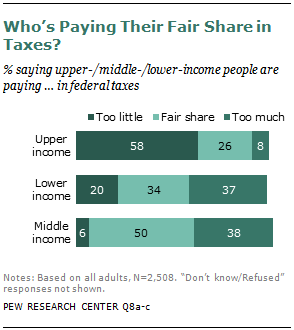

Nearly six-in-ten survey respondents (58%) also say the rich pay too little in taxes, while 26% say they pay their fair share, and just 8% say they pay too much. Even among those who describe themselves as upper or upper-middle class1, 52% say upper-income Americans don’t pay enough in taxes.

In spite of these views, overwhelming majorities of self-described middle- and lower-class Americans say they admire people who get rich by working hard (92% and 84%, respectively).2

The new survey, which was conducted July 16-26, 2012, among 2,508 adults nationwide, finds that a majority of the public (65%) thinks the nation’s income gap between rich and poor has grown in the past decade—and most say that’s a bad thing for the country.

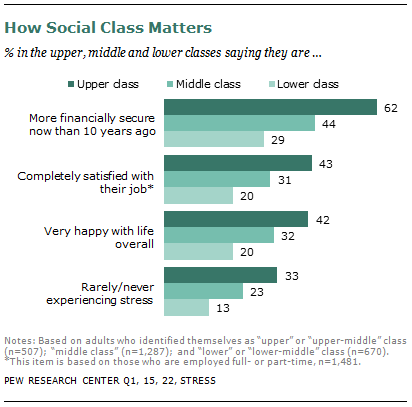

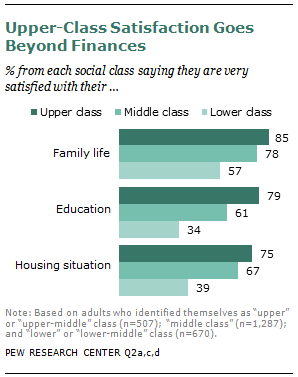

The survey also finds that the gap between rich and poor goes far beyond income. Adults who self-identify as being in the upper or upper-middle class are generally happier, healthier and more satisfied with their jobs than are those in the middle or lower classes. And they are much less likely to have suffered economic hardships as a result of the recession. In addition, those in the upper class are more satisfied than those in the middle or lower classes with their family life, their housing situation and their education. Upper-class Americans even report experiencing less stress. Only 29% of those in the upper class say they frequently experience stress, compared with 37% of those in the middle class and 58% of lower-class adults.

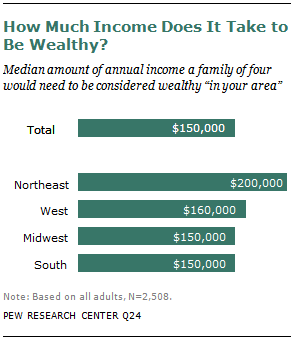

When asked how much income it would take for a family to be considered wealthy in their area, most Americans say a family of four would need at least $100,000. Some 39% say they would need between $100,000 and $249,999, and 30% say it would take $250,000 or more. The median amount for all respondents was $150,000. The public estimates a family of four would need about half as much income ($70,000) to lead a middle-class lifestyle in their area. As would be expected, the responses vary significantly by region of the country, as well as by income and other demographic characteristics.

These survey findings present challenges for both political parties, but more so for the Republicans than the Democrats. More than six-in-ten Americans (63%) say the GOP favors the rich over the middle class and poor, and 71% believe the policies of a President Mitt Romney would be good for wealthy people. Much smaller shares say the same about the Democratic Party (20%) and the policies of President Barack Obama in a second term (37%). When it comes to Obama, more say his policies will help the poor (60%) than say they will help the middle class (50%) or the wealthy (37%). By contrast, just 31% say Romney’s policies would help the poor and 40% say they would help the middle class.

For Better and Worse, the Rich Are Different

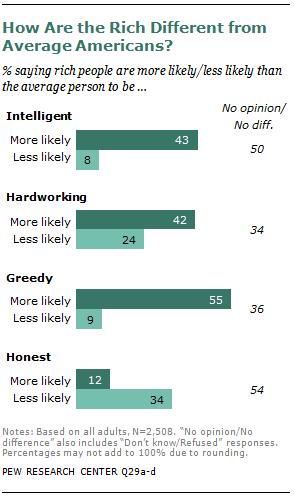

In 1926 F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote that the rich are “different from you and me.” His observation may still ring true today. About four-in-ten adults (43%) say that rich people are more likely than average Americans to be intelligent, while 8% say rich people are less likely than average Americans to be intelligent, and 50% have no opinion on the matter.

A similar share of adults (42%) say rich people are more likely than average Americans to be hardworking. About half as many (24%) say rich people are less likely than average Americans to be hardworking, and 34% don’t have an opinion.

On the negative side, more than half of all adults (55%) say rich people are more likely than the average person to be greedy. Only 9% say they are less likely to be greedy. The remaining 36% have no opinion. About one-third of the public (34%) says the rich are less likely than average people to be honest. Only 12% say they are more likely to be honest, and 54% have no opinion on this.

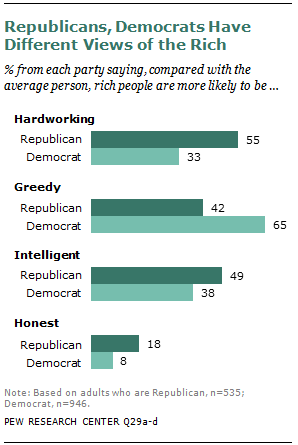

Republicans and Democrats view the rich differently. A much higher share of Republicans (55%) than Democrats (33%) say, compared with the average person, rich people are more likely to be hardworking. Republicans are also more likely than Democrats to view rich people as more intelligent than average. Roughly half of Republicans (49%) say rich people are more likely to be intelligent. Only 38% of Democrats agree.

For their part, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to view the rich as greedy. Roughly two-thirds of Democrats (65%) say the rich are more likely than average Americans to be greedy. Only 42% of Republicans agree with this assessment of the rich. Democrats also have a less positive view of the rich when it comes to honesty. While 18% of Republicans say rich people are more likely than average to be honest, only 8% of Democrats agree. There is widespread agreement across social classes on the relative intelligence of the rich. At least four-in-ten self-described upper-, middle- and lower-class adults believe the rich are more likely than average Americans to be intelligent, and less than 10% from each group say they are less likely to be intelligent.

There is much less agreement on the other traits. Upper-class adults are more likely than middle- and lower-class adults to see the rich as being more hardworking than average Americans (51% of the upper class vs. 44% of the middle class and 35% of the lower class say the rich are more likely to be hardworking). Middle- and lower-class adults are more likely than upper-class adults to view the rich as less honest than average people. And lower-class adults are much more likely than those in the upper or middle classes to view the rich as greedy.

Social Class, Tax Fairness and Partisanship

Another widely held perception of the rich is that they do not pay their fair share in taxes. A majority of adults (58%) say that upper-income people pay too little in federal taxes. One-in-four (26%) say upper-income people pay their fair share in taxes, and 8% say they pay too much in taxes. Even among those who consider themselves upper or upper-middle class, fully 52% say upper-income people pay too little. Only 10% of this group says upper-class adults say people pay too much in taxes.

The public is divided over whether lower-income people pay the appropriate amount in federal taxes. Some 37% say lower-income people pay too much in taxes, while roughly as many (34%) say lower-income people pay their fair share in taxes. One-in-five adults say lower-income people pay too little in taxes. There is little agreement across social classes on this issue, with a plurality of lower-class adults (48%) saying lower-income people pay too much in taxes and a plurality (39%) of upper-income adults saying lower-income people pay their fair share. When it comes to the middle-class tax burden, there is no clear consensus among the public. Half of all adults say middle-income people pay their fair share in federal taxes. Nearly four-in-ten (38%) say middle-income people pay too much in taxes, and 6% say they pay too little.

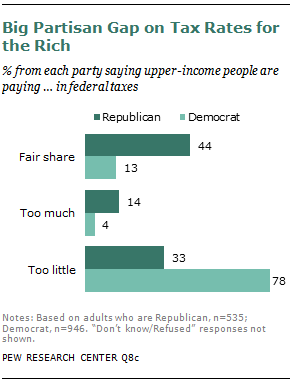

Partisanship is closely linked to views about federal taxes, and the biggest gaps emerge over tax rates for the rich. A solid majority of Republicans say upper-income people pay either their fair share (44%) or too much (14%). Among Democrats, a strong majority (78%) say upper-income people pay too little in taxes; only 33% of Republicans agree. Some 13% of Democrats say upper-income people pay their fair share in taxes, while 4% say the rich are paying too much.

Partisans also divide over whether low-income people pay the right amount of taxes. A plurality of Democrats (48%) say low-income people pay too much, while Republicans are divided over whether low-income people pay their fair share (34%) or too little (30%). Only 23% of Republicans say lower-income people pay too much.

These partisan differences fade away on the issue of middle-class taxes. Democrats and Republicans have nearly identical views about the tax burden faced by middle-income Americans. Roughly half say middle-income people pay their fair share in taxes (52% of Republicans and 51% of Democrats). Nearly four-in-ten say middle-income people pay too much in taxes (39% of Republicans and 37% of Democrats). Very few from either party say middle-income people pay too little (3% of Republicans and 8% of Democrats).

Are the Rich Getting Richer?

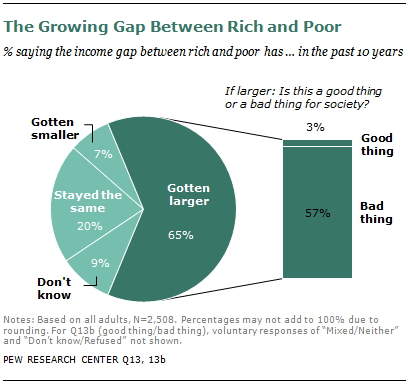

The notion that the rich are not paying their fair share in taxes is compounded by the public’s perception that the income gap between the rich and the poor has widened in recent years. Roughly two-thirds of Americans (65%) say the income gap between the rich and poor has gotten larger in the past decade. And 57% also say this is a bad thing for society (3% say this is a good thing). Only 7% say the gap has gotten smaller, and 20% say it has stayed about the same.

The economic data bear out the public’s perception that the gap has widened. Whether the metric is income or wealth, the rich have outpaced the poor in recent decades. A Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data shows that incomes have risen much more sharply for the wealthiest Americans over the past 40 years, and as a result the upper-income tier of the public now takes in a much larger share of U.S. aggregate household income than it did in the past. In addition, an even larger gap in wealth (measured by assets, minus debt, accumulated over time) has emerged, particularly in the past 10 years with the collapse of the housing market.3

Upper-, middle- and lower-class adults all recognize the growing income gap. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say the gap has increased (70% vs. 57%).

A separate Pew Research survey measured perceptions of a rising income gap in starker terms. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “Today it’s really true that the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer.” Three-quarters of respondents (76%) agreed. However, there was much less agreement across parties and social classes. Roughly nine-in-ten Democrats (92%) agreed that the rich just get richer while the poor get poorer, compared with only 56% of Republicans. Among adults from different social classes, those who describe themselves as lower class were the most likely to agree that the rich are getting richer while the poor get poorer (84%). Even so, solid majorities of middle- (71%) and upper-class (66%) adults concurred.4

The Demographics of Social Class

Who are the rich? In terms of their demographic profile, upper-class Americans are distinct from those in the middle and lower classes in some respects. In other ways they are no different. Overall, 17% of respondents in the Pew Research survey described themselves as upper or upper-middle class. Roughly one-third (32%) labeled themselves lower-middle or lower class, and 49% described themselves as middle class.

Income is closely correlated with social class identification. Among the self-described upper or upper-middle class, 40% have an annual household income of $100,000 or more. This compares with 13% of self-described middle-class adults and 3% of lower or lower-middle class adults.

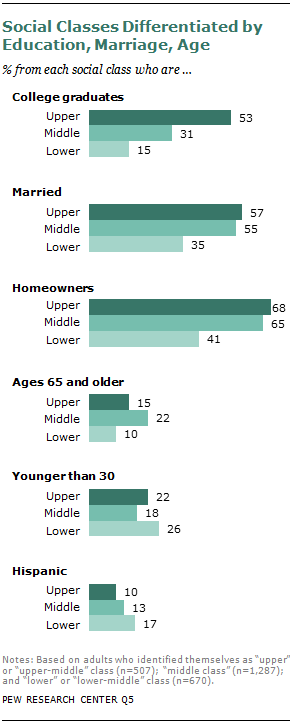

Education is also closely linked to social class. Among those who identify as being upper or upper-middle class, 53% have a bachelor’s degree or more. Among middle-class adults, 31% have a college degree. And among the lower or lower-middle class, only 15% are college graduates. Nearly one-in-five lower-class adults (18%) do not have a high school diploma.

Marital status is closely linked to social class. Upper-class adults are no different from middle-class adults in this regard, but lower-class adults are much less likely than either group to be married. More than half of upper-class (57%) and middle-class (55%) adults are married. This compares with only 35% of lower-class adults.

Similarly, upper- and middle-class adults are equally likely to own their own home, while lower-class adults are less likely to be homeowners. Roughly two-thirds of upper- and middle-class adults own a home, compared with 41% of those in the lower class.

Lower-class adults stand out in terms of age and ethnicity. Young adults are much more heavily represented among the lower class than are older adults. Fully 26% of those in the lower class are under age 30, while only 10% of those in the lower class are age 65 or older. Some 17% of lower-class adults are of Hispanic origin, compared with only 13% of middle-class adults and 10% of the upper class.

Life Is Good in the Upper Class

Upper-class Americans clearly do stand out from those in the middle and lower classes when it comes to their economic well-being. Overall, upper-class adults are much more satisfied with their current financial situation than are those in the middle and lower classes. About half (49%) of all upper-class adults say they are very satisfied with their personal financial situation. This compares with 32% of middle-class adults and 13% of those in the lower class.

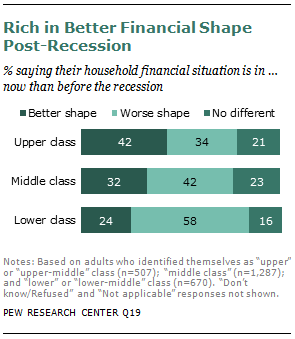

And the recession has had less of a long-lasting impact on the upper class. About four-in-ten upper-class adults (42%) say they are in better shape now than they were before the recession started in December 2007. About one-third (34%) say they are in worse shape, and 21% say their financial situation is unchanged. Among both the middle and lower classes, the assessments are much more negative. More than four-in-ten middle-class adults (42%) say they are in worse financial shape now than they were before the recession; 32% say they are in better shape. Among lower-class adults, 58% say they are in worse shape now, while only 24% say they are in better shape.

In addition, upper-class adults are more likely than lower- or middle-class adults to have experienced rising economic mobility over the course of their lives. Roughly half (53%) of those in the upper class say their standard of living now is much better than their parents’ standard of living was at a comparable age. Only 37% of those in the middle class say the same, and among lower-class adults, the share is even smaller (25%). However, when it comes to their children’s futures, upper-class adults are no more optimistic than those in the middle or lower class. Only about one-quarter from each of the social classes say they think their children’s standard of living will be much better than their own.

Only about one-third (34%) of those who currently describe themselves as upper class say their family was upper class when they were growing up. A similar share of upper-class adults say they were middle class, and 32% say their family was in the lower class when they were growing up. Among middle- and lower-class adults, relatively few (16% and 12%, respectively) say their family was upper class when they were growing up.

Looking ahead, upper-class adults are optimistic about their own financial security and relatively upbeat about the country’s prospects. Some 43% are very confident that they will have enough income and assets to last throughout their retirement years. This compares with 23% of middle-class adults and only 11% of those in the lower class.

When asked about the country’s long-term economic future, upper-class adults are optimistic on balance: 57% say they are very or somewhat optimistic about the country’s economic future, and 40% say they are somewhat or very pessimistic. Middle-class views are similar to those of the upper class in this regard (55% are positive, 41% negative). Those in the lower class are considerably more negative. Only 38% are optimistic about the nation’s economic future, while 55% are pessimistic.

The widespread sense of well-being among upper-class adults extends beyond their financial lives. When compared with middle- and lower-class adults, they are more likely to say they are making progress in their careers, and those who are employed are more satisfied with their jobs. Among those who are not retired, 84% of upper-class adults say they are making progress in their careers. This compares with 76% of non-retired middle-class adults and 54% of those in the lower class.

Upper-class adults are also more highly satisfied with their family life than are middle- and lower-class adults. Some 85% of those in the upper class say they are very satisfied with their family life, compared with 78% of middle-class adults and 57% of lower-class adults. Similarly, upper-class adults are more satisfied with their housing situation (75% very satisfied, vs. 67% of middle-class adults and 39% of lower-class adults) and with their education (79% vs. 61% and 34%, respectively).

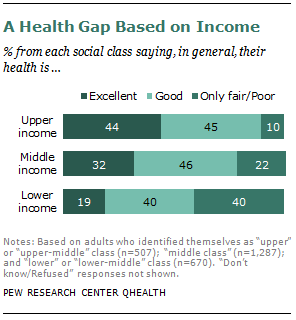

Upper-class adults are also happier and healthier than those in the middle and lower classes. Four-in-ten upper-class adults (42%) say they are very happy with their lives overall. This compares with 32% of middle-class adults and 20% of lower-class adults. The gaps are almost identical when it comes to personal health. While 44% of upper-class adults rate their health as excellent, only 32% of middle-class adults and 19% of lower-class adults say the same. Among those in the lower class, four-in-ten rate their health as only fair (29%) or poor (11%).

Upper Class Largely Immune from Day-to-Day Economic Hardships

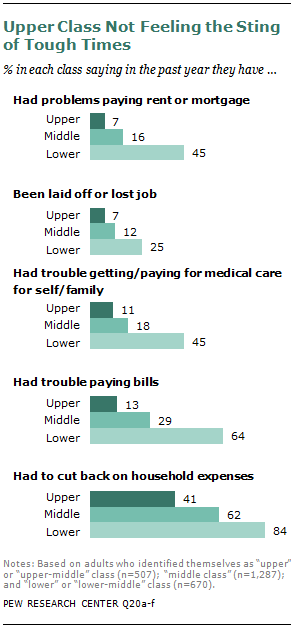

Although the recession officially ended more than three years ago, many Americans continue to experience the lingering effects of the economic downturn. Upper-class adults have not completely escaped these lasting effects, but their experience has been tempered by their greater economic security. Self-described upper-class adults are much less likely than those in the middle and lower classes to have experienced a variety of economic hardships in the past year.

Overall, about one-quarter of American adults (23%) say they have had problems paying their rent or mortgage in the past year. Only 7% of upper-class adults fall into this category. Middle-class adults are about twice as likely to say they had trouble with their rent or mortgage payments (16%). For the lower class, this has been a much bigger problem. Lower-class adults are about six times as likely as upper-class adults to say they had difficulty paying their rent or mortgage in the past year (45%).

Some 15% of all adults say they were laid off or lost their job in the past year. Again, upper-class adults are much less likely to have faced this challenge. Only 7% of upper-class adults say they lost their job in the past year. This compares with 12% of middle-class adults and 25% of those in the lower class.

About one-in-ten upper-class adults (11%) report that they had trouble getting or paying for medical care for themselves or someone in their family in the past year. Middle-class adults are more likely to have experienced this (18%). And for lower-class adults, this problem is fairly widespread. Some 45% of lower-class adults say they had trouble getting or paying for medical care this past year.

When it comes to paying the bills more generally, a similar pattern can be seen. Only 13% of upper-class adults report that they had trouble paying the bills in the past year. This compares with 29% of middle-class adults and 64% of those in the lower class.

A solid majority of all Americans (65%) say they have had to cut back on household spending in the past year because money was tight. Four-in-ten upper-class adults (41%) say they have cut back on spending. The share is higher for middle-class adults (62%). And among lower-class adults, about eight-in-ten (84%) say they have had to cut back on expenses.

What Does It Take to Be Wealthy?

Survey respondents were asked to estimate how much a family of four would need in annual income to be considered wealthy in their area. Roughly seven-in-ten say a family of four would need at least $100,000 to be considered wealthy. Three-in-ten say a family of four would need $250,000 or more. Overall, the median amount given was $150,000. Self-described upper- and middle-class respondents estimate a somewhat higher median—$200,000. For lower-class respondents the median was $150,000. By comparison, among all adults, the estimated median amount needed to live a middle-class lifestyle is $70,000.

Because the cost of living varies widely across the country, estimates of how much income is needed to be considered wealthy differ across regions and types of community. Among those living in the Northeast, the median amount is $200,000. The median for those living in the West is $160,000, and for those in the South and Midwest it is somewhat lower ($150,000).

Those living in suburban communities give a higher estimate of what it would take to be considered wealthy in their area than do those living in urban or rural areas. The median amount is $200,000 for respondents living in a suburban community. The median is $180,000 among those living in urban areas. Rural residents have significantly lower estimates for what is needed to be wealthy where they live. Their median value is only $125,000.

The Parties, the Candidates and Social Class

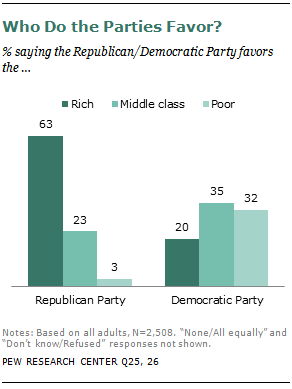

As the Republican Party continues to court middle-class voters throughout the fall campaign, it will have to contend with the widespread perception that it is the party of the rich. More than six-in-ten Americans (including 62% who identify themselves as middle class) say the GOP favors the rich over the middle and lower classes. About one-in-four (23%) say the Republican Party favors the middle class, and a mere 3% say the GOP favors the poor.

The public expressed similar views of the Republican Party leading up to the last presidential election, when John McCain was the GOP’s standard-bearer. In 2008, 59% of the public said the Republican Party favored the rich (compared with a somewhat higher 63% now), 21% said the GOP favored the middle class (compared with 23% now), and 3% said the party favored the poor (identical to the share in the current poll).

Similarly, there has been relatively little change in perceptions about the Democratic Party. It is still the case that the public doesn’t see the Democrats as clearly favoring one class over another. Some 20% now say the Democrats favor the rich (up slightly from 16% who said this in 2008), 35% say the Democrats favor the middle class (compared with 38% in 2008), and 32% say they favor the poor (up slightly from 27% in 2008).

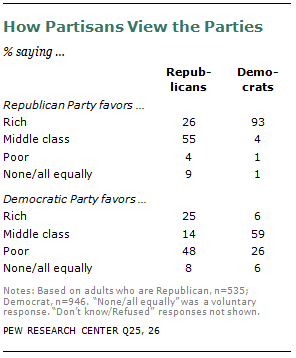

These overall numbers mask sharp differences among partisans themselves. Most Republicans don’t see their party as favoring the rich over other social classes. A plurality of Republicans (55%) say the GOP favors the middle class, while only 26% say their party favors the rich and 4% say their party favors the poor. Democrats overwhelmingly believe the Republican Party favors the rich (93%).

At the same time, most Democrats (59%) say their party favors the middle class. One-in-four Democrats (26%) say their party favors the poor, and 6% say it favors the rich. Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say the Democratic Party favors the poor (48%). Only 14% of Republicans say the Democrats favor the middle class.

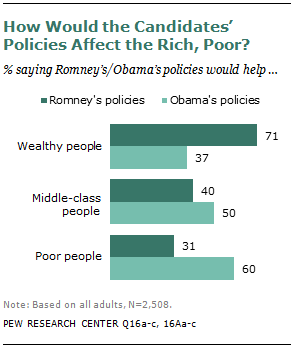

When it comes to the candidates themselves, the public sees a potential Romney presidency being much more beneficial for the rich than for the middle class or the poor. Fully 71% of all adults say that if Romney is elected president, his policies would help wealthy people. Less than half (40%) believe Romney’s policies would help the middle class, and only 31% think Romney’s policies would help the poor.5

The public has a much different impression of the potential impact of Obama’s policies in a second term. A 60% majority says Obama’s policies would help the poor, and half say they would help the middle class. Only 37% say his policies would be beneficial to wealthy people.

Upper-, middle- and lower-income adults are largely in agreement over the potential impact of the candidates’ policies. Roughly seven-in-ten from each group say Romney’s policies would help the wealthy. Far fewer upper- (46%) and middle-class (42%) adults say Romney’s policies would help middle-class people. Lower-class adults are even less likely to agree (34%). Similarly, while about one-third of upper- and middle-class adults say Romney’s policies would help the poor, just 26% of those who describe themselves as lower class agree.

Evaluations of how Obama’s policies might affect these groups do not differ as much by social class. About six-in-ten upper- and middle-class adults (62%) and 55% of lower-class adults say Obama’s policies in a second term would help the poor. Roughly half from each group say they would help the middle class. Among the middle and lower classes, 38% say Obama’s policies would help the wealthy; 34% of upper-class adults say the same.

About the Report

The general public survey is based on telephone interviews conducted July 16-26, 2012, with a nationally representative sample of 2,508 adults ages 18 and older. The survey included an oversample of 407 non-Hispanic blacks and 377 Hispanics. A total of 1,505 interviews were completed with respondents contacted by landline telephone and 1,003 with those contacted on their cellular phone. Data are weighted to produce a final sample that is representative of the general population of adults in the continental United States. Survey interviews were conducted in English and Spanish under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International. Margin of sampling error is plus or minus 2.8 percentage points for results based on the total sample at the 95% confidence level.