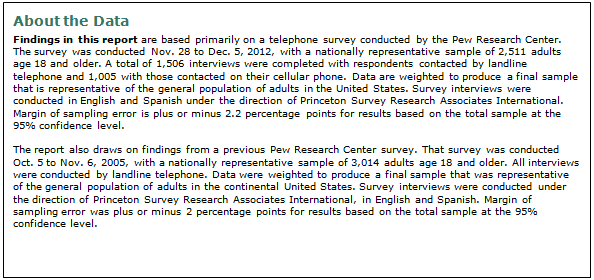

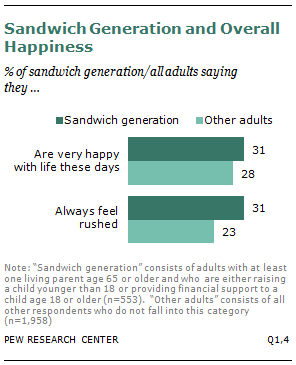

With an aging population and a generation of young adults struggling to achieve financial independence, the burdens and responsibilities of middle-aged Americans are increasing. Nearly half (47%) of adults in their 40s and 50s have a parent age 65 or older and are either raising a young child or financially supporting a grown child (age 18 or older). And about one-in-seven middle-aged adults (15%) is providing financial support to both an aging parent and a child.

While the share of middle-aged adults living in the so-called sandwich generation has increased only marginally in recent years, the financial burdens associated with caring for multiple generations of family members are mounting. The increased pressure is coming primarily from grown children rather than aging parents.

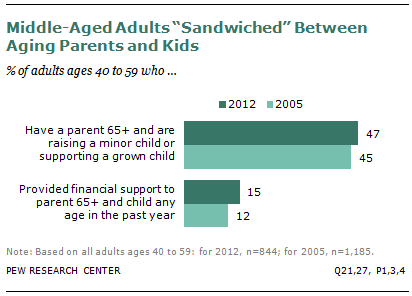

According to a new nationwide Pew Research Center survey, roughly half (48%) of adults ages 40 to 59 have provided some financial support to at least one grown child in the past year, with 27% providing the primary support. These shares are up significantly from 2005. By contrast, about one-in-five middle-aged adults (21%) have provided financial support to a parent age 65 or older in the past year, basically unchanged from 2005. The new survey was conducted Nov. 28-Dec. 5, 2012 among 2,511 adults nationwide.

Looking just at adults in their 40s and 50s who have at least one child age 18 or older, fully 73% have provided at least some financial help in the past year to at least one such child. Many are supporting children who are still in school, but a significant share say they are doing so for other reasons. By contrast, among adults that age who have a parent age 65 or older, just 32% provided financial help to a parent in the past year.

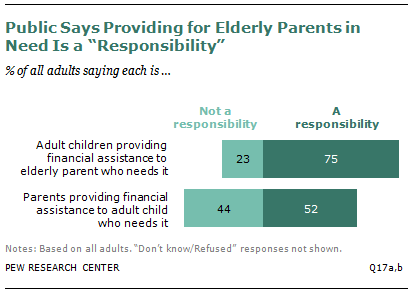

While middle-aged adults are devoting more resources to their grown children these days, the survey finds that the public places more value on support for aging parents than on support for grown children. Among all adults, 75% say adults have a responsibility to provide financial assistance to an elderly parent who is in need; only 52% say parents have a similar responsibility to support a grown child.

One likely explanation for the increase in the prevalence of parents providing financial assistance to grown children is that the Great Recession and sluggish recovery have taken a disproportionate toll on young adults. In 2010, the share of young adults who were employed was the lowest it had been since the government started collecting these data in 1948. Moreover, from 2007 to 2011 those young adults who were employed full time experienced a greater drop in average weekly earnings than any other age group.1

A Profile of the Sandwich Generation

Adults who are part of the sandwich generation—that is, those who have a living parent age 65 or older and are either raising a child under age 18 or supporting a grown child—are pulled in many directions.2 Not only do many provide care and financial support to their parents and their children, but nearly four-in-ten (38%) say both their grown children and their parents rely on them for emotional support.

Who is the sandwich generation? Its members are mostly middle-aged: 71% of this group is ages 40 to 59. An additional 19% are younger than 40 and 10% are age 60 or older. Men and women are equally likely to be members of the sandwich generation. Hispanics are more likely than whites or blacks to be in this situation. Three-in-ten Hispanic adults (31%) have a parent age 65 or older and a dependent child. This compares with 24% of whites and 21% of blacks.

More affluent adults, those with annual household incomes of $100,000 or more, are more likely than less affluent adults to be in the sandwich generation. Among those with incomes of $100,000 or more, 43% have a living parent age 65 or older and a dependent child. This compares with 25% of those making between $30,000 and $100,000 a year and only 17% of those making less than $30,000.

Married adults are more likely than unmarried adults to be sandwiched between their parents and their children: 36% of those who are married fall into the sandwich generation, compared with 13% of those who are unmarried. Age is a factor here as well, since young adults are both less likely to be married and less likely to have a parent age 65 or older.

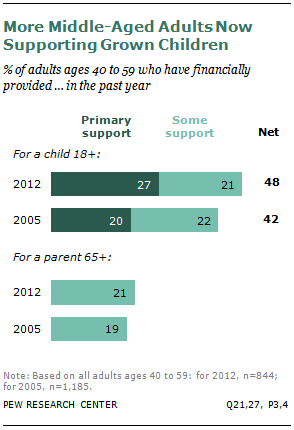

Presumably life in the sandwich generation could be a bit stressful. Having an aging parent while still raising or supporting one’s own children presents certain challenges not faced by other adults—caregiving and financial and emotional support to name just a few. However, the survey suggests that adults in the sandwich generation are just as happy with their lives overall as are other adults. Some 31% say they are very happy with their lives, and an additional 52% say they are pretty happy. Happiness rates are nearly the same among adults who are not part of the sandwich generation: 28% are very happy, and 51% are pretty happy.

Sandwich-generation adults are somewhat more likely than other adults to say they are often pressed for time. Among those with a parent age 65 or older and a dependent child, 31% say they always feel rushed even to do the things they have to do. Among other adults, the share saying they are always rushed is smaller (23%).

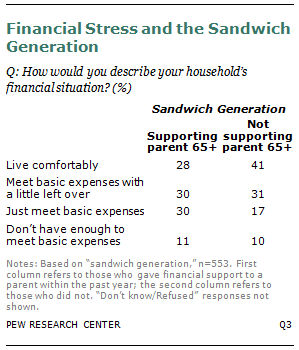

For members of the sandwich generation who not only have an aging parent but have also provided financial assistance to a parent, the strain of supporting multiple family members can have an impact on financial well-being.3 Survey respondents were asked to describe their household’s financial situation. Among those who are providing financial support to an aging parent and supporting a child of any age, 28% say they live comfortably, 30% say they have enough to meet their basic expenses with a little left over for extras, 30% say they are just able to meet their basic expenses and 11% say they don’t have enough to meet even basic expenses. By contrast, 41% of adults who are sandwiched between children and aging parents, but not providing financial support to an aging parent, say they live comfortably.

Family Responsibilities

When survey respondents were asked if adult children have a responsibility to provide financial assistance to an elderly parent in need, fully 75% say yes, they do. Only 23% say this is not an adult child’s responsibility. By contrast, only about half of all respondents (52%) say parents have a responsibility to provide financial assistance to a grown child if he or she needs it. Some 44% say parents do not have a responsibility to do this.

When it comes to providing financial support to an aging parent in need, there is strong support across most major demographic groups. However, there are significant differences across age groups. Adults under age 40 are the most likely to say an adult child has a responsibility to support an elderly parent in need. Eight-in-ten in this age group (81%) say this is a responsibility, compared with 75% of middle-aged adults and 68% of those ages 60 or older. Adults who are already providing financial support to an aging parent are no more likely than those who are not currently doing this to say this is responsibility.

On the question of whether parents have a responsibility to support their grown children, personal experience does seem to matter. Parents whose children are younger than 18 are less likely than those who have a child age 18 or older to say that it is a parent’s responsibility to provide financial support to a grown child who needs it (46% vs. 56%). And those parents who are providing primary financial support to a grown child are among the most likely to say this is a parent’s responsibility (64%).

Financial Support for Aging Parents and Grown Children

While most adults believe there is a responsibility to provide for an elderly parent in financial need, about one-in-four adults (23%) have actually done this in the past year. Among those who have at least one living parent age 65 or older, roughly one-third (32%) say they have given their parent or parents financial support in the past year. And for most, this is more than just a short-term commitment. About seven-in-ten (72%) of those who have given financial assistance to an aging parent say the money was for ongoing expenses.

Similar shares of middle-aged, younger and older adults say they have provided some financial support to their aging parents in the past year. It is worth noting that many parents age 65 or older may not be in need of financial assistance, so there is not necessarily a disconnect between the share saying adult children have a responsibility to provide for an aging parent who is in need and the share who have provided this type of support.

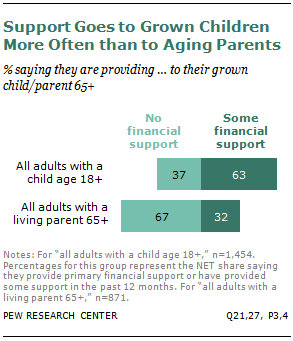

Overall, Americans are more likely to be providing financial support to a grown child than they are to an aging parent. Among all adults, 30% say they have given some type of financial support to a grown child in the past year. Among those who have a grown child, more than six-in-ten (63%) have done this.

Here the burden falls much more heavily on adults who are middle-aged than on their younger or older counterparts. Among adults ages 40 to 59 with at least one grown child, 73% say they have provided financial support in the past year. Among those ages 60 and older with a grown child, only about half (49%) say they have given that child financial support. Very few of those under age 40 have a grown child.

Of those middle-aged parents who are providing financial assistance to a grown child, more than half say they are providing the primary support, while about four-in-ten (43%) say they are not providing primary support but have given some financial support in the past 12 months. Some 62% of the parents providing primary support say they are doing so because their child is enrolled in school. However, more than one third (36%) say they are doing this for some other reason.

The focus in this report is on the financial flows from middle-aged adults to their aging parents and their grown children. Of course, money also flows from parents who are 65 or older to their middle-aged children. While the new Pew Research survey did not explore these financial transfers, previous surveys have found that a significant share of older adults provide financial help to their grown children. A Pew Research survey conducted in Sept. 2011 found that among adults 65 and older with at least one grown child age 25 or older, 44% said they had given financial support to a grown child in the past year.4

Beyond Finances: Providing Care and Emotional Support

While some aging parents need financial support, others may also need help with day-to-day living. Among all adults with at least one parent age 65 or older, 30% say their parent or parents need help to handle their affairs or care for themselves; 69% say their parents can handle this on their own.

Middle-aged adults are the most likely to have a parent age 65 or older (68% say they do). And of that group, 28% say their parent needs some help. Among those younger than 40, only 18% have a parent age 65 or older; 20% of those ages 60 and older have a parent in that age group. But for those in their 60s and beyond who do still have a living parent, the likelihood that the parent will need caregiving is relatively high. Fully half of adults age 60 or older with a living parent say the parent needs help with day-to-day living.

When aging adults need assistance handling their affairs or caring for themselves, family members often help out. Among those with a parent age 65 or older who needs this type of assistance, 31% say they provide most of this help, and an additional 48% say they provide at least some of the help.

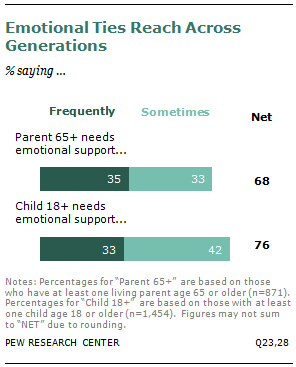

In addition to helping their aging parents with day-to-day living, many adults report that their parents rely on them for emotional support. Among all adults with a living parent age 65 or older, 35% say that their parent or parents frequently rely on them for emotional support, and 33% say their parents sometimes rely on them for emotional support. One-in-five say their parents hardly ever rely on them in this way, and 10% say they never do.

Even among those who say their parents do not need help handling their affairs or caring for themselves, 61% say their parents rely on them for emotional support at least sometimes. For those whose parents do need help with daily living, fully 84% report that their parents rely on them for emotional support at least some of the time.

Not surprisingly, the older the parent, the more likely he or she is to require emotional support. Among adults with a parent age 80 or older, 75% say their parents turn to them for emotional support frequently or sometimes. This compares with 64% among those who have a parent ages 65 to 79.

Emotional support also flows from parents to grown children, even children who are financially independent. Overall, 33% of parents with at least one child age 18 or older say their grown child or children depend on them frequently for emotional support. An additional 42% say their grown children sometimes rely on them for emotional support.

When it comes to grown children, there is a link between financial and emotional support. Among parents who say they are providing primary financial support to their grown child or children, 43% say their children frequently rely on them for emotional support and 45% say they sometimes do. By comparison, only 24% of those who say they do not provide any financial support to their grown children say their children frequently rely on them for emotional support, and 39% say their children sometimes rely on them for this type of support.

Boomers Moving Out of the Sandwich Generation

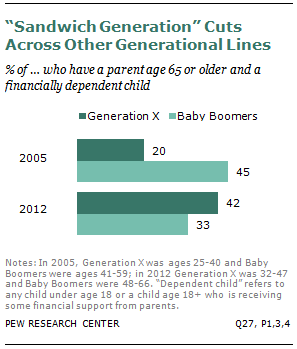

Today members of the Baby Boomer generation and Generation X are represented in the “sandwich generation.” But the balance has shifted significantly. When the Pew Research Center explored this topic in 2005, Baby Boomers made up the majority of the sandwich generation. They were more than twice as likely as members of the next generation—Generation X—to have a parent age 65 or older and be supporting a child (45% vs. 20%). Since 2005, many Baby Boomers have aged out of the sandwich generation, and today adults who are part of Generation X are more likely than Baby Boomers to find themselves in this situation: 42% of Gen Xers have parent age 65 or older and a dependent child, compared with 33% of Boomers.5

This report will focus largely on adults ages 40 to 59, loosely defined as “middle aged.” While this group may not share a generational label, many of its members do have a shared set of experiences, challenges and responsibilities given the unique position they inhabit, sandwiched between their children and their aging parents.

Middle-aged adults who make up the core of the sandwich generation are living out these challenges and, in the process, perhaps ushering in a new set of family dynamics. Most middle-aged parents with grown children say their relationship with their children is different from the relationship they had with their own parents at a comparable age. Half say the relationship is closer, while 12% say it’s less close and 37% say the relationship is about the same. Older adults (those ages 60 and older) are less likely than middle-aged parents to say they have a closer relationship with their grown children than they had with their own parents (44%), and they are more likely to say the relationship is about the same (45%).

The remainder of this report will look at the basic building blocks of intergenerational relationships in more detail. The first section will look at attitudes about financial responsibilities and the reality of financial transfers. The second section will look at caregiving for older adults. How many older adults need assistance with day-to-day living, and who is providing that care? The third section will look at emotional ties across generations and explore the extent to which aging parents rely on their children and grown children rely on their parents for emotional support.