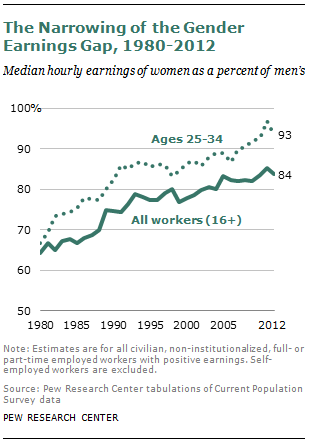

Three decades ago, U.S. women overall made 64% as much as men did in hourly earnings. In 2012, they made 84%—a remarkable narrowing of the gender gap in pay, as well as an illustration of its persistence.

The relative gains are even more striking for American women at the outset of their working lives. Among young adults, ages 25 to 34, women’s hourly earnings were two-thirds (67%) of men’s in 1980 and fully 93% of men’s in 2012. But if past trends are any indication, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of government data, today’s young women may lose some of those gains as they grow older.

Both the long-term reduction of the gender pay gap and its endurance are linked to larger changes in American society. Change came rapidly in the 1980s and has slowed since then.

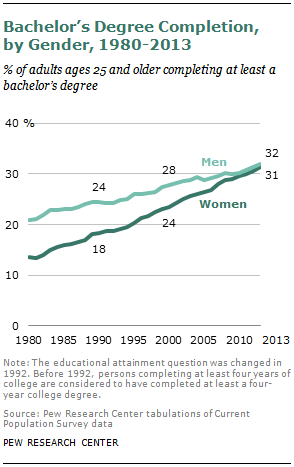

The gender gap narrowed as women, especially mothers, surged into the labor force beginning in the 1950s, building up experience to compete against men. More recently, younger women have outpaced men in college-going and college graduation, which have opened doors to higher-paying jobs, often in male-dominated fields. In addition, larger forces such as globalization and weakened unions disproportionately have hurt some types of jobs mainly held by men.12

At the same time, women make less than men in part because they still trail men in labor market experience. Women remain twice as likely as men to work part time, and they take time off more often from employment over their working lives—in large part to care for children or other family members. Although women have ¬increased their share of well-paid jobs such as lawyers and managers, research indicates that they remain concentrated in female-dominated lesser-paying occupations and that integration slowed over the past decade.13

In contrast to women, men are more likely to work when they have young children. They work longer hours than women, even in full-time jobs, and some evidence indicates the financial reward for such “overwork” has risen in recent years.14

A notable amount of the gender gap, though, is hard to quantify. How much is due to gender stereotypes that contribute to lower aspirations by women before they even reach the job market? Or is due to weaker professional networks once they look for work? Do women lose out because they do not push as hard as men for raises and promotions? And what is the role of discrimination, which turns up in experiments where people are asked to rate identical resumes from mothers and fathers?15

The amount of the earnings gap that is unexplained by measured factors, such as educational attainment and job type, ranges widely in published research. One recent study, using 2000 data, said that unexplained factors account for just over 20% of the gap, a second, using 2007 data, said 24% to 35% of the gap could not be explained and a third (which looked only at full-time workers in 1998) said 41% could not be accounted for.16

In addition, there is an open question whether the gender pay gap will continue to decrease. That is because change has slowed since the mid-1990s on two key factors: the increase in women’s labor force participation and the narrowing of the gender gap in work experience.17

This chapter explores the demographic, economic and educational explanations behind the trends in the gender gap in pay. The main data sources used here are the Current Population Survey and the American Time Use Survey, both administered by the Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Earnings Trends by Gender

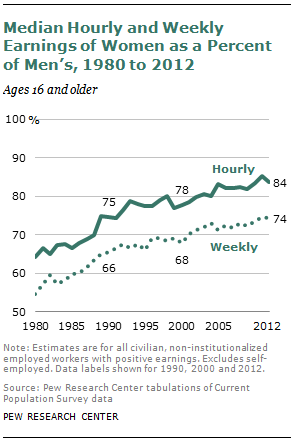

The gender gap in pay varies somewhat based on the metric used to analyze it, but by all measures it has narrowed since 1980, though more slowly in recent years. This report analyzes differences mainly through the lens of median hourly earnings, which is the usual weekly earnings divided by the usual hours worked in a week. This measure accounts for the difference in earnings between women and men that may arise from differences in the number of hours worked.

In 2012, median hourly earnings were $14.90 for women and $17.79 for men, so women made 84% as much as men. In 1980, median hourly earnings (adjusted to 2012 dollars) were $11.94 for women and $18.57 for men, meaning that women made 64% of what men did that year. During this time period, women’s earnings have risen (25%) and men’s have declined (4%).

Women made rapid gains relative to men in the 1980s and early 1990s, but the pace has slowed since then. During the 15 years from 1980 to 1995, the male-female gap narrowed by 20% (or 13 percentage points). For the 16 years from 1996 to 2012, it narrowed by 8% (or six percentage points).

By age group, the gender gap in earnings is smallest, and has narrowed most sharply, among adult workers at the outset of their working lives, ages 25 to 34. In this age group, women earned 93% as much as men the same age in 2012, compared with 67% in 1980.

The youngest women (ages 16 to 24) made 90% as much as men the same age in 2012, and 84% in 1980. For women ages 35 to 44, the ratio was 80% in 2012 and 58% in 1980. For women ages 45 to 54, the ratio was 77% in 2012 and 57% in 1980. For women ages 55 to 64, the ratio was 77% in 2012 and 58% in 1980.

Only one group—women ages 65 and older—has experienced a decline in their earnings relative to those of men the same age: Their ratio was 82% in 2012, slightly worse than the 84% in 1980.

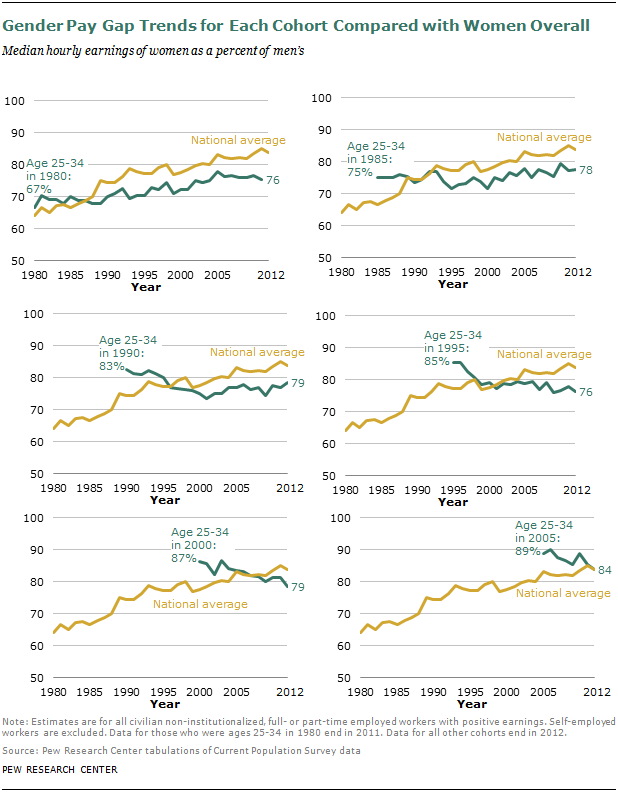

Cohort Analysis

Looking at data on successive cohorts of women, they typically begin their working lives at earnings levels closer to men the same age than is true for women overall. However, as the women age, they fail to keep pace with the overall narrowing of the earnings gap. As a result, within 10 to 15 years of entering the labor force, the newer workers slip behind the ratio for women overall, and in many cases lose ground compared with their younger selves.

For example, women who were ages 25 to 34 in 1990 made 83% as much in hourly earnings as men the same age did that year, more than the 75% ratio for women overall. In 2000, when this group of women and men were ages 35 to 44, the women made 75% as much as the men, less than the 78% ratio for all women. In 2012, when this group was ages 47 to 56, the women earned 79% as much as men the same age—lower than the overall ratio of 84%, and below their own ratio in 1990.18

For the most recent cohorts of young women—those who were ages 25 to 34 in 1990, 1995, 2000 and 2005—pay gaps with men the same age have widened as they grew older, even as the gap for all women narrowed somewhat. For women who were ages 25 to 34 in 1980 and 1985, pay gaps with men the same age shrank as they grew older, but their current gap is larger than that for all women; when they were young workers, the gap had been smaller.

Labor Force Trends

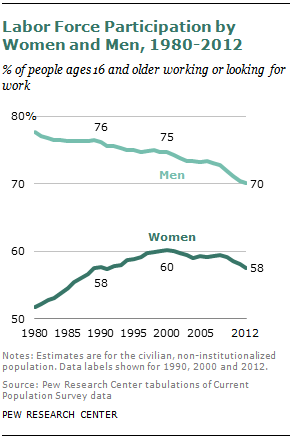

The trends in pay equality have taken place alongside growth in the share of women, especially mothers, who are working or looking for work. However, key differences remain between male and female labor patterns¬ that explain some of the continuing pay gap: Men on average regularly work more hours than women and take less time out of the labor force over their working lives.19

Women’s labor force participation rose to 58% in 2012 from 52% in 1980. During that same period, men’s labor force participation declined to 70% from 78%. Because of these trends, women account for a growing share of the U.S. labor force, 47% in 2012, compared with 43% in 1980.

Labor force participation is higher for women in each age group now than in 1980 except for 16- to 24-year-olds (who are increasingly likely to be in school). Among men, all age groups except those 65 and older had lower labor force participation in 2012 than in 1980.

Part Time and Full Time

One major gender difference that affects overall earnings is that working women are twice as likely as working men to work part time (less than 35 hours a week), a pattern that has changed little in recent decades.

In 2012, 26% of women ages 16 and older worked part time, about the same as in 1980 (27%). Among men ages 16 and older, 13% worked part time in 2012, compared with 11% in 1980. (The shares for both women and men rose slightly since the onset of the Great Recession in 2007.)

The share of part-timers is highest for the youngest and oldest age groups, but at least one-in-five women works part time in the prime working ages of 25 to 64, compared with one-in-ten men of comparable age.

Overall, women made up 43% of the full-time workforce and 64% of the part-time workforce in 2012.

The use of hourly earnings as a measure of compensation factors in women’s greater likelihood to work part time. Another metric—weekly earnings—produces a somewhat greater gender earnings gap (though a similar time trend) because it does not adjust for part-time work. In 2012, women made 74% of what men made in weekly earnings, compared with 84% when expressed in hourly earnings.

Among full-time workers, women’s weekly earnings were 80% of men’s; looking at hourly earnings of full-time workers, women made 86% of what men made in 2012. Some of the difference in weekly earnings is due to female workers putting in fewer hours than men. In 2012, 26% of men working full-time reported working more than 40 hours per week, but only 14% of women working full-time reported doing so.20

Among part-time workers, women actually make more than men: 105% of men’s earnings using weekly earnings as a metric and 107% using hourly earnings as a metric. One explanation for this, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is that men who work part time are on average younger than women who do, and younger workers make less money. In 2012, 43% of male part-time workers were 16 to 24 years old, compared with 29% of female workers who were in that age group.21 However, even among part-time workers ages 25 to 64, women have higher median hourly earnings than men, so the relative youth of the male part-time workforce may not be the full explanation.

Family Roles

As the Pew Research survey and time use data show, women are more likely than men to take a significant amount of time off to care for children or other family members.

Employment data show that nearly all married men with children younger than 5 are in the workforce (95% in 2012). Among women, those who are married with children younger than 5 are far less likely be in the workforce (62% in 2012).

Still, the surge of women with young children at home into the labor market led the rise in women’s labor force participation over the past three decades. Married women with children age 5 or younger at home increased their labor force participation rate from 45% in 1980 to 62% in 2012. Likewise, single or cohabiting women with children age 5 or younger increased their labor force participation rate from 55% in 1980 to 70% in 2012. Rates for comparable men changed little over this period.

Rates for married and unmarried women with older children (ages 6-17) also increased, though not as rapidly. Women are more likely to be in the labor force if their children are older than if they are younger. However, men’s labor force participation (especially for married men) is not greatly linked to the age of their children at home.

Overall, marriage has a positive link to labor force participation for men, but not a clear link for women. Married men are more likely than unmarried men to be in the workforce. Among women, unmarried women are slightly more likely to be working.

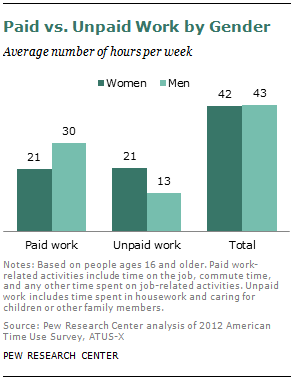

Time use data also underscore the greater likelihood that women will step back from paid work to do unpaid work such as child care. According to data from time diaries, women on average spend about the same number of hours each week doing paid and unpaid work, while men devote more hours to paid work. Among all people ages 16 and older, men spend an average 30 hours a week on paid work and women spend 21.22 Women average 21 hours a week on unpaid work such as housework and caring for children or other family members, while men average 13 hours a week on such activities.

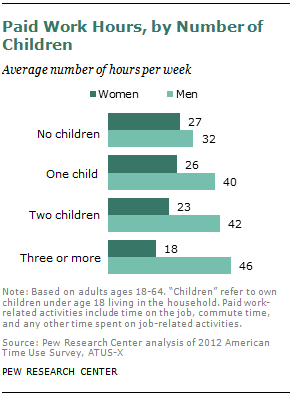

The presence of a child at home is related differently to the work hours of women and men. Women with children at home spend less time on paid work than women without children, 23 hours per week compared with 27. Men with children at home spend more time on paid work, 42 hours a week compared with 32 for men without children at home. The more children they have, according to time use data on adults ages 18 to 64, the less time women spend on paid work and the more time men do.

Mothers with the youngest children at home spend less time on job-related activities—20 hours per week for women whose youngest children are age 2 or younger, compared with 27 hours per week for women whose youngest children are 13 to 17 years old. For men, work hours peak when their youngest child is 3 to 12 years old.23

The changed composition of the young female workforce may have played a role in narrowing the overall pay gap because these younger women are less likely than previous cohorts of young women to have family responsibilities. Among women ages 25 to 34, half were married in 2012, compared with 70% of their 1980 counterparts. Nearly half (46%) had no children at home, compared with only a third (31%) in 1980. Those most likely to postpone marriage and childbearing are college graduates; as the next section shows, they make up a growing share of women, especially younger ones.

Education and Occupation

A major factor in reducing the gender gap in earnings is that women have upgraded their educational attainment, and younger women have surpassed men in college graduation rates. Workers with college degrees not only make more money than those with less education, but also are the only educational attainment group to have experienced a meaningful gain in earnings from 1980 to 2012. Among women, hourly earnings for the college-educated have grown 33% since 1980; among men, the gain was 12%. The earnings of workers with less education either were flat, for women, or declining, for men.

The overall gender parity in college education has been driven by new cohorts of women. Women ages 18 to 24 are more likely than comparably aged men to be enrolled in college—45% vs. 38% in 2012—and women ages 25 to 32 are more likely than comparably aged men to have completed college—38% vs. 31% in 2013. These gaps, in favor of women, emerged in the 1990s.

As might be expected, women make up a rising share of college-educated workers. In 2012, about half (49%) of employed workers with at least a bachelor’s degree were women, up from 36% in 1980.

In each educational attainment group, women’s hourly earnings are now a higher percentage of men’s than was the case in 1980. But college-educated women do no better than less-educated women when it comes to the ratio of their earnings to those of comparably educated men. In 2012, women with at least a college degree earned 79% as much as comparably educated men. That was the same as or less than women with some college education but no bachelor’s degree (who earned 81% as much as comparably educated men), high school graduates (80%) and women without a high school diploma (83%).

As their labor force participation increased, women also widened their representation across the occupational spectrum. Job segregation—that is, concentration of women in lower-paying occupations—has declined, and women have moved into more well-paying occupations that were once dominated by men. This movement has been stronger into professional and managerial jobs than for blue-collar occupations.24

But the trend conceals the fact that key gaps remain within general categories of work, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Survey data. For example, a higher share of female workers (13%) than male workers (3%) was employed in health-care occupations in 2012. However, within health-care occupations, median hourly earnings of women were only 75% of what men made in 2012.

One possible reason for this disparity was that a higher share of men employed in health care (82%) than women (66%) worked in practitioner and technical occupations. A higher share of women (34%) than men (18%) worked in support occupations.25

In addition, some research finds that occupational integration has slowed. According to one recent study, segregation among full-time, full-year workers did not decline substantially in the 2000s for the first time since the 1960s.26 This affects the gender pay gap because pay levels in female-dominated occupations, on average, are less than those in male-dominated occupations.