One of the first ways Americans encounter science, technology, engineering and math is through their early education. And many look back fondly at their science and math classes during this time in their lives. Three-quarters of Americans say they liked science classes in grades K-12, citing labs and activities as a key reason why. And, a smaller majority recalls liking math classes in grades K-12. STEM workers are more likely than those working in other fields to say they liked science or math classes in school, but still more than four-in-ten non-STEM workers say they liked both subjects in grades K-12.

Many of those who work in occupations outside of STEM also say they were once interested in pursuing a job or career in STEM. Most of these non-STEM workers considered working in STEM while in school or in their 20s rather than later in life. The most common reasons these workers give for not pursuing a STEM job or career were cost and time barriers, such as the amount of money and the number of years required for specialized training.

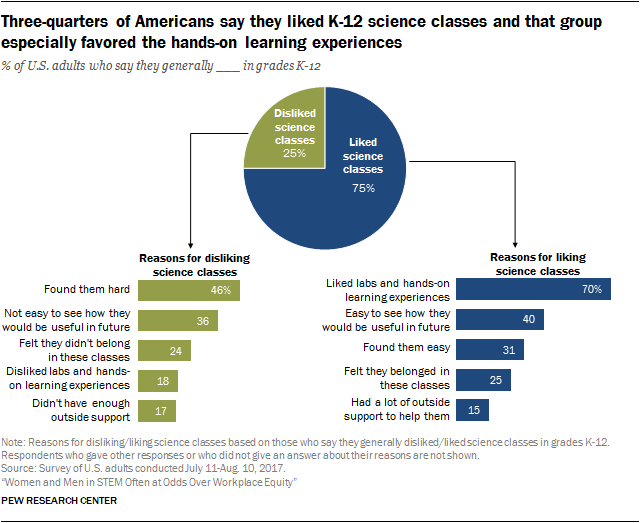

Looking back, three-quarters of Americans say they liked K-12 science classes

About four-in-ten STEM workers say they had an older family member in STEM

Role models, often parents or other close family members, are considered by many to be important for career development. Overall, roughly four-in-ten STEM workers (41%) say at least one of their older, close family members works or worked in STEM. By comparison, 26% of those working in other occupations say they have or had an older family member working in a STEM job or career. Some 44% of women in STEM jobs and 37% of men say they have or had a close older family member working in STEM.

Three-quarters of Americans say they liked science classes in grades K-12, while only one-quarter say they disliked science classes.

When forced to choose whether the subject matter or teaching was the main reason they liked science classes, most point to the subject matter. About two-thirds (68%) say the subject matter was the main reason they liked science classes in grades K-12, while roughly three-in-ten (31%) say the main reason they liked science classes was the way they were taught.

Similarly, among those who disliked science classes in grades K-12, more say the reason they disliked science classes was the subject matter than the way the classes were taught (61% vs. 36%).

The survey also asked respondents to select from a list of possible reasons for liking or disliking science classes. Among those who liked science classes, most enjoyed the labs and hands-on learning experiences (70%). Fewer say it was easy to see how science would be useful for the future (40%) or they found science classes easy (31%).

Among those who disliked science classes, the most commonly selected reason is that they found science classes to be too hard (46%). Many say they disliked science classes because they did not see how science would be useful for the future (36%).

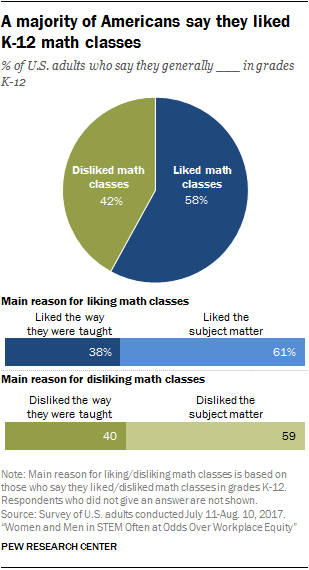

As Americans reflect on K-12 experiences, more say they liked than disliked math classes

Americans are somewhat less enthusiastic about the math classes they took in school, by comparison. About six-in-ten (58%) say they liked K-12 math classes, while roughly four-in-ten (42%) say they disliked K-12 math classes.

Most Americans point to the subject matter as the main reason they liked or disliked math classes, rather than the way math classes were taught. About six-in-ten (61%) say they liked K-12 math classes because of the subject matter. A similar share (59%) says they disliked math classes because of the subject matter.

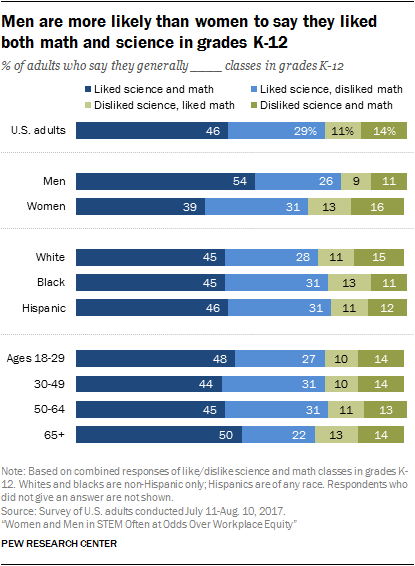

Higher shares of men than women say they liked both science and math classes in K-12

Almost half (46%) of Americans say they liked both science and math classes in grades K-12. About one-in-ten (11%) say they liked math but not science, while a larger share (29%) disliked math but liked science. Some 14% say they disliked both math and science classes.

Men are more likely than women to say they liked both math and science classes (54% vs. 39%). Women are slightly more inclined than men to say they liked only science classes (31% vs. 26%) or they disliked both (16% vs. 11%).

Whites, blacks and Hispanics are about equally likely to say they liked both math and science classes in grades K-12. Similarly, there are no significant differences by age.

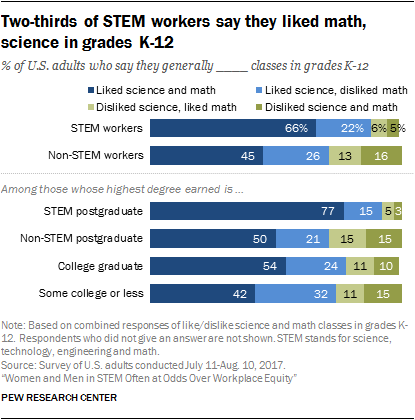

As one might expect, working in STEM or earning a postgraduate degree in a STEM field is closely related to liking science and math classes in grades K-12, but many of those who work in other occupations or have a degree in a different field liked one or both of these subjects too.

Two-thirds of STEM workers (66%) say they liked both math and science in grades K-12. Among non-STEM workers, 45% say they liked both, a much larger share than say they disliked both (16%).

There are wide differences among those working in STEM, however. Engineers are among the most likely to say they liked both math and science classes in grades K-12 (86%). Health-related workers (53%) are only slightly more likely than non-STEM workers to say they liked both. About three-in-ten health-related workers (31%) say they liked science but disliked math.

Similarly, about three-quarters of adults with a postgraduate degree in a STEM field (77%) say they liked both science and math classes in grades K-12. Among those holding a postgraduate degree in other fields, half say they liked both science and math classes.

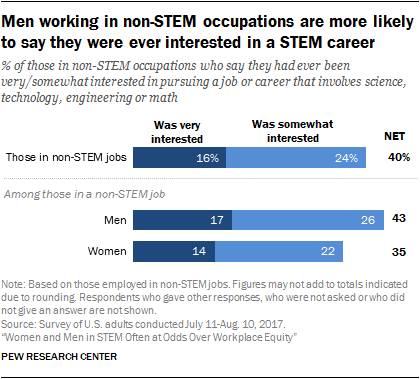

Among those in other types of jobs, four-in-ten were once at least somewhat interested in a STEM job or career

Four-in-ten Americans who currently work in non-STEM occupations say that they were “very” (16%) or “somewhat” (24%) interested in pursuing a career in science, technology, engineering and math at some point. About half (48%) say they were not too interested (21%) or not interested at all (27%) in pursuing a job or career in STEM.

Another roughly one-in-ten of this group (9%) say that their current job or career involves STEM. Many jobs and careers outside of STEM involve science, technology, engineering and math skills and knowledge.39 Of those who say their current job involves STEM, about two-in-ten (18%) work in management, while about one-in-ten (12%) work in business and finance operations.

Men working in a non-STEM occupation are a bit more likely to say that they were ever interested in pursuing a career in STEM (43% vs. 35% of women in non-STEM jobs). There are no more than modest differences among whites (37%), blacks (41%) and Hispanics (45%) on this measure.

Those who have or had an older family member working in STEM are modestly more likely than those who didn’t have an older family member in STEM to say they were once interested in a STEM job or career (48% vs. 36%).40

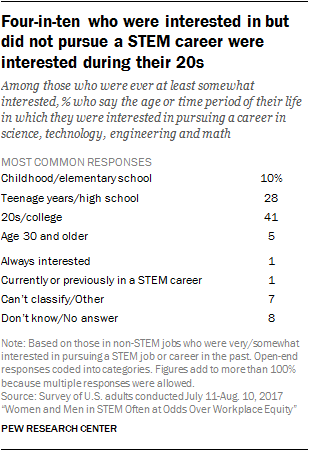

When asked when in their life they were interested in pursuing a STEM job or career, most pointed to when they were in high school, college or during their 20s. About four-in-ten (41%) say that they had this interest in college or during their 20s and another 28% say they were interested in high school or their teenage years. Fewer say they were interested in pursuing a STEM career early in life, in elementary school or their childhood (10%) or later in life over the age of 30 (5%).

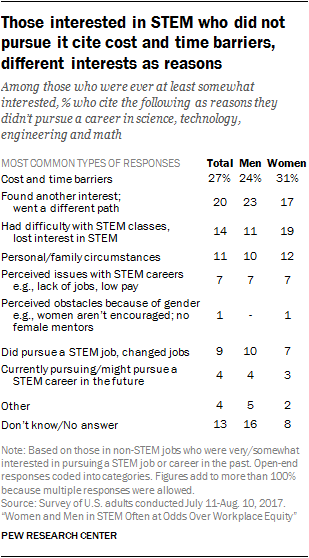

When asked why they did not end up pursuing a career or job in STEM, the most commonly cited reason was cost and time barriers (27%), such as the large amount of time and money required for education or a general lack of access to resources and opportunities.

But others pointed to different reasons for not pursuing a STEM career. One-in-five (20%) say that they chose to pursue a different career instead of STEM, because they developed a different interest.

Some 14% say that they did not end up in a STEM career because they struggled to do well in STEM classes or just lost interest in STEM. A similar share (11%) cites personal or family circumstances.

There are modest gender differences in reasons cited for not pursuing a career in STEM. Women are more likely than men to cite cost and time barriers (31% vs. 24%) and struggling in STEM classes or losing interest (19% vs. 11%); while men are somewhat more likely to say that they found another interest (23% vs. 17%).

“Middle-skills” STEM workers are particularly likely to have had additional training

“Middle-skills” jobs, which require additional training beyond a high school education but not a four-year college degree, make-up an important part of the STEM workforce. Middle-skills jobs are particularly common in computer technology and health care.

About three-in-ten STEM workers (28%) have some college experience (including an associate degree) but no bachelor’s degree. This is a similar share to those employed in non-STEM occupations (31%). Among those with some college experience, STEM workers earn 35% more than their non-STEM counterparts ($54,745 vs. $40,505). See Chapter 1.

STEM middle-skills workers are distinct from middle-skills workers in other occupations because they are more likely to have additional educational training that is directly related to their job. STEM workers are more likely than non-STEM workers to have completed any vocational or technical training, a certificate, or apprenticeship. Among those with some college experience or an associate degree, about seven-in-ten STEM workers (69%) say they have completed this kind of training, compared with about half of non-STEM workers (49%).

In addition, among workers with an associate degree, STEM workers are more likely than workers in other occupations to say their job is closely related to their education. Some 77% of STEM workers with an associate degree say their job is very closely related to their degree. In contrast, about three-in-ten (28%) of those working in other occupations say their associate degree is closely related to their current job, while a larger share (42%) say their degree is not related or not very closely related to their job.

Similarly, STEM workers with an associate degree are about three times more likely than their non-STEM counterparts to say they use the skills and knowledge from their degree in their current job all the time (73% vs 24%).