Americans are narrowly hopeful about the future of the United States over the next 30 years but more pessimistic when the focus turns to specific issues, including this country’s place in the world, the cost of health care and the strength of the U.S. economy.

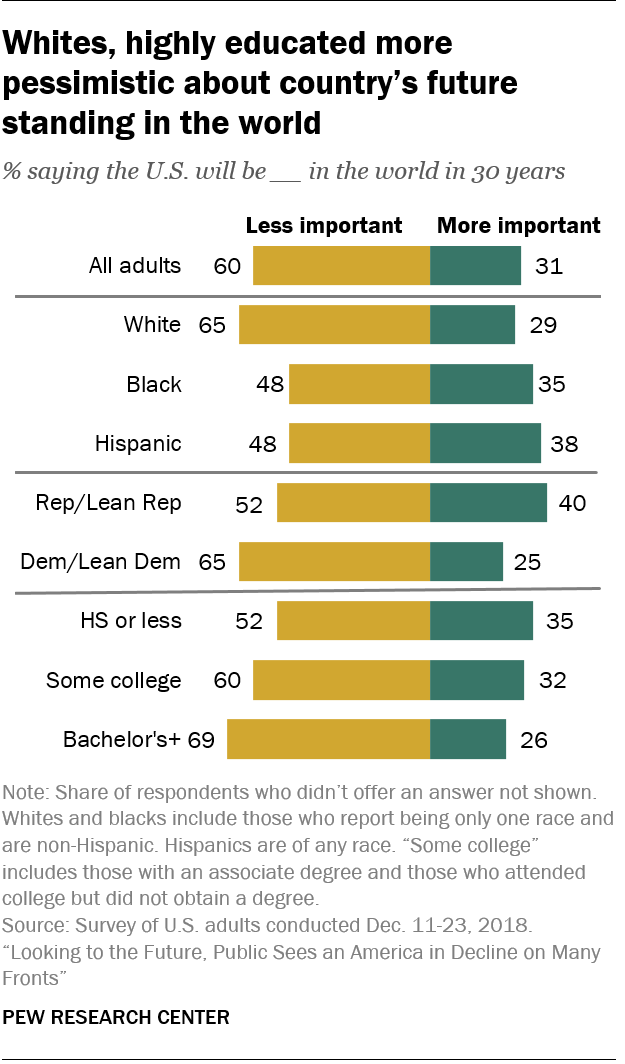

Overall, six-in-ten adults predict that that the U.S. will be less important in the world in 2050. While most key demographic groups share this view, it is more widely held by whites and those with more education. About two-thirds of whites (65%) forecast a diminished role in the world for the U.S. in 30 years, a view shared by 48% of blacks and Hispanics. Roughly seven-in-ten adults with a bachelor’s or higher degree (69%) see a lesser role internationally for America. By contrast, six-in-ten of those with some college education (but no bachelor’s degree) and 52% of those with less education are as pessimistic about the country’s future world stature.

The current partisan political debate over the country’s proper role in the world is mirrored in these results. About two-thirds of Democrats and independents who lean Democratic (65%), but closer to half of Republicans and Republican leaners (52%), think America will be a diminished force in the world in 2050. These differences are even greater among partisans at opposite ends of the ideological scale: 72% of self-described liberal Democrats but 49% of conservative Republicans say the U.S. will be less important internationally in 30 years.

As they see the importance of the U.S. in the world receding, many Americans expect the influence of China will grow. About half of all adults (53%) expect that China definitely or probably will overtake the United States as the world’s main superpower in the next 30 years. As with U.S. standing in the world, large party differences emerge on this question. About six-in-ten Democrats (59%) but just under half of Republicans (46%) predict that China will supplant the U.S. as the world’s main superpower.

The public predicts another 9/11 – or worse – by 2050

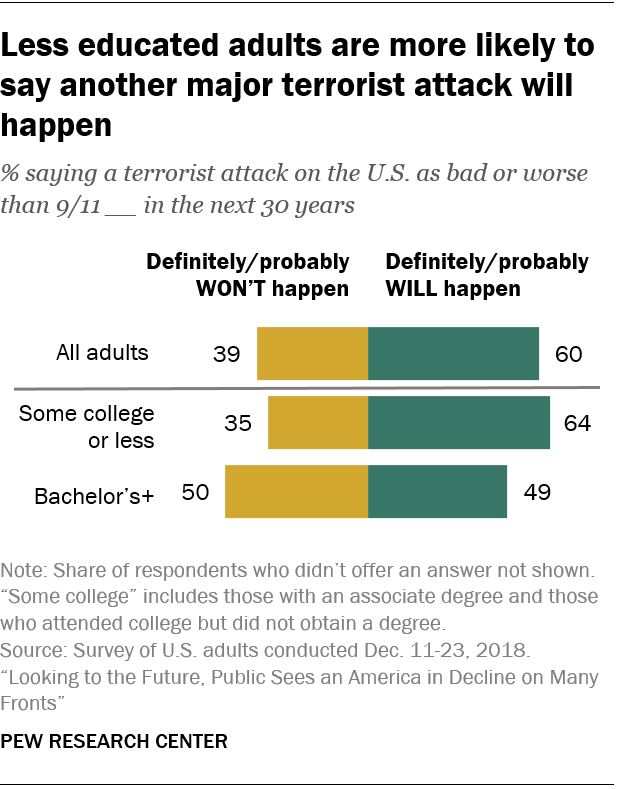

For an overwhelming majority of Americans, the 9/11 terrorist attacks stand as the most important historic event in their lifetimes. As Americans look ahead to 2050, six-in-ten say that a terrorist attack on the U.S. as bad or worse than 9/11 will definitely (12%) or probably (48%) happen.

This troublesome prediction is widely expressed by most major demographic groups. Roughly equal proportions of whites (61%), blacks (56%) and Hispanics (59%) say such a terrorist attack is likely sometime in the next 30 years, and so do 57% of men and 62% of women. While Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say such an attack will definitely or probably happen, majorities in each group express this view (63% of Republicans and 57% of Democrats).

At the same time, some demographic differences do emerge. Those with some college or less education are more likely than college graduates to expect another 9/11 (64% vs. 49%) by 2050. And Americans who are 50 or older are more likely than younger adults to say this will happen.

Narrow majority sees a weaker economy in 2050

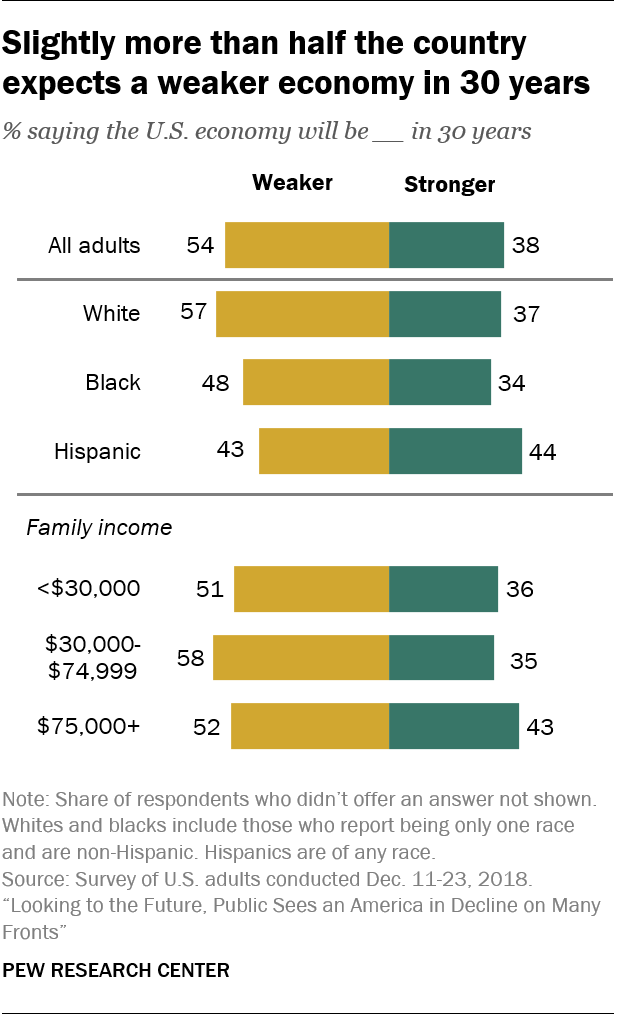

Just over half of the public (54%) predicts that the U.S. economy in 30 years will be weaker than it is today, while 38% say it will be stronger. Similarly, larger shares of most key demographic groups forecast a less robust rather than a more vigorous economy in 2050.

Whites are somewhat more pessimistic than blacks or Hispanics about the future financial health of the country: 57% of whites compared with 48% of blacks and 43% of Hispanics predict a weaker economy in 30 years.

Roughly half or more of every income group predict a weaker economy in the next 30 years. However, Americans in higher-earning families are somewhat more likely than lower-earners to say the economy will be better in 2050 than it is today. About four-in-ten adults (43%) with family incomes of $75,000 or higher say the economy will be stronger, a view shared by 35% of those earning less.

The partisan divides on views about the future of the economy are substantial. Roughly six-in-ten Democrats (58%) predict a weaker economy in 2050, while a third say it will be stronger. By contrast, Republicans are divided: 49% forecast a worsening economy, but 45% expect economic conditions to improve over the next 30 years.

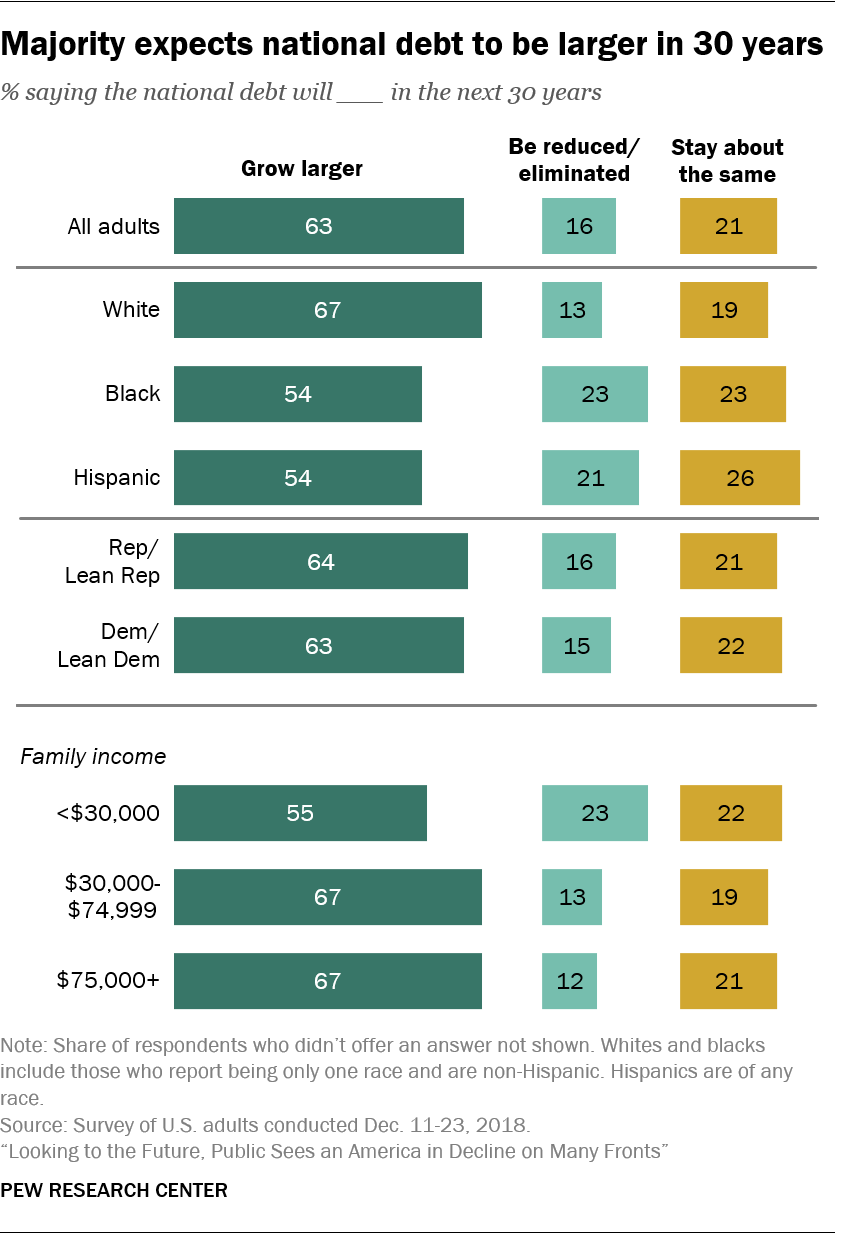

The public is also pessimistic about the future course of the national debt. About six-in-ten (63%) say the national debt – the total amount of money the federal government has borrowed – will increase, while just 16% predict it will be reduced or eliminated. Two-in-ten (21%) say it will stay relatively unchanged from what it is today.

These predictions of a growing government debt are consistent with recent history. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal debt held by the public is projected to reach 78% of the U.S. gross domestic product in 2019 – up from 34% in 2000.

Similar to projections about the overall economy, virtually every key demographic group is more likely to predict that government debt will grow larger than to predict it will shrink. Higher- and middle-income adults are more likely than those with lower incomes to expect the debt to rise: 67% of Americans with family incomes of $30,000 or more say the debt will grow larger by 2050, compared with 55% of those with incomes under $30,000. Whites also are more likely than blacks or Hispanics to say the national debt will rise (67% vs. 54% for both blacks and Hispanics). At the same time, virtually identical shares of Republicans (64%) and Democrats (63%) forecast a growing national debt.

Among the other looming threats to the U.S. economy: a major worldwide energy crisis, which two-thirds of the public say will definitely (21%) or probably (46%) occur in the next 30 years. While substantial majorities of every major demographic group predict a global power emergency, Hispanics and lower-income adults are particularly likely to see this occurring. About three-quarters of Hispanics (76%) and adults with family incomes of less than $30,000 (73%) expect a major energy crisis in the next 30 years. By contrast, 64% of whites and 60% of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more share this pessimistic view.

Differences on this question between political partisans are particularly large. About three-quarters (76%) of Democrats but 55% of Republicans expect a serious global energy crisis in the next 30 years.

Public predicts growing income inequality and an expanding lower class

About three-quarters of all Americans (73%) expect the gap between the rich and the poor to grow over the next 30 years, a view shared by large majorities across major demographic and political groups.

Differences between some groups do emerge, but only the size of the majorities differ and not the underlying belief that income inequality will grow. About three-quarters of whites (77%) but smaller majorities of blacks (62%) and Hispanics (64%) expect income inequality to increase by 2050. Similarly, about three-quarters of those who attended or graduated from college (77%) say the gap between the rich and the poor will increase, a view shared by two-thirds of those with a high school diploma or less education. Roughly equal shares of Republicans and Democrats expect income inequality to grow (71% and 75%, respectively).

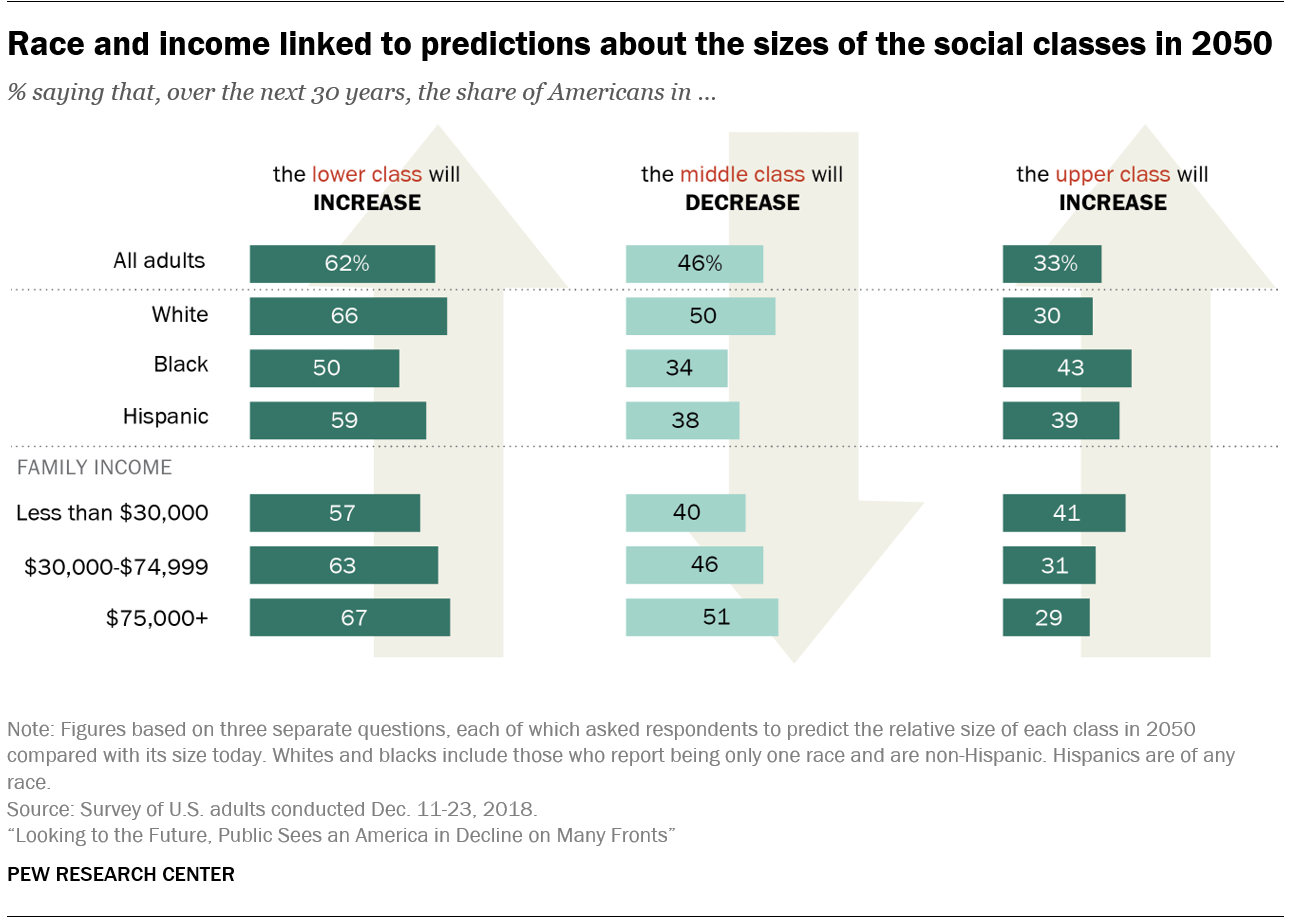

The growing rich-poor gap is not the only cloud the public sees on the economic horizon. About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say the share of people in the lower class will increase by 2050. At the same time, just under half (46%) predict that the relative size of the middle class will shrink, while 28% say it will grow larger, and about the same share (26%) say it will not change.

Americans are less certain about future changes in the share of Americans in the upper class. The predominant expectation is that the upper class will remain about the same relative size that it is today, a view held by 44% of the public. A larger share predicts that the proportion of Americans in the upper class will increase than say it will get smaller (33% vs. 22%).

Race and family income are closely associated with these views. Whites are significantly more likely than blacks to predict that the relative size of the lower class will increase (66% vs. 50%) and that the middle class will shrink (50% vs. 34%). Whites are less likely than blacks to say the upper class will grow (30% vs. 43%). Hispanics’ views on the future of the lower class are similar to those of whites and blacks, but in their perceptions of the future relative size of the middle and upper classes, Hispanics are closer to blacks (38% say the middle class will get smaller; 39% predict the upper class will increase).

Regardless of their income category, majorities of Americans predict that the size of the lower class will increase as a share of the total population. But those closer to the top of the income ladder are somewhat more likely to forecast a growing lower class than those who are closer to the bottom. Two-thirds (67%) of Americans with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more say the lower class will grow, a view shared by 57% of those with incomes of $30,000 or less. Higher-earners also are more likely than those with less family income to say the relative size of the middle class will shrink (51% vs. 40%). At the same time, Americans with a family income of $75,000 or more are less likely than those with annual family incomes under $30,000 to expect a larger share of Americans to be in the upper class in 2050 (29% vs. 41%).

Partisan differences on these questions are relatively modest. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say that the share of Americans in the lower class will grow (65% vs. 59%) and the middle class will shrink (50% vs. 42%). About a third of both parties predict that the relative size of the upper class will increase.

Divided views on the future of race relations but some hopeful signs

The public is uncertain whether the troubled state of race relations today will still be a feature of American life in 2050. About half (51%) say race relations will improve over the next 30 years, but 40% predict that they will get worse.

Unlike the large differences that mark views of blacks and whites on many race-related questions, the racial divide on this question is narrower. A slight majority of whites (54%) predict that race relations will improve in the next 30 years, while 39% say they will worsen. Blacks split down the middle: 43% predict better relations between the races and the same percentage predict they will be worse. Hispanics also split roughly equally, with 45% expecting improved relations and 42% saying they will get worse.

Optimism about the future of race relations is closely related to educational attainment. Six-in-ten adults with a bachelor’s or higher degree predict that race relations will improve. By contrast, 47% of those with less education are hopeful about the future of race relations.

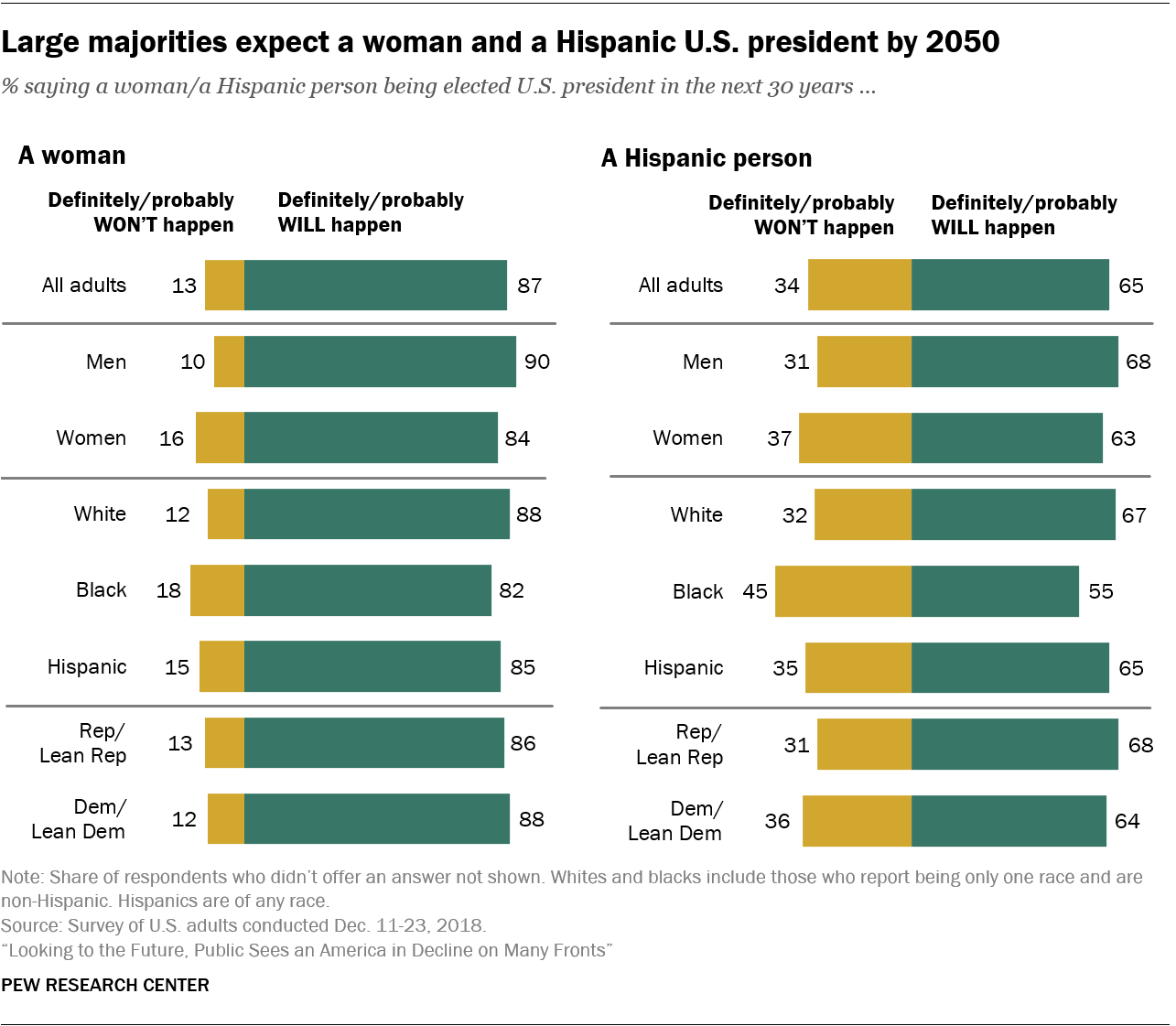

Other findings suggest the public thinks barriers that have blocked some groups from leadership positions in politics may ease in the future. Nearly nine-in-ten (87%) predict that a woman will be elected U.S. president by 2050 (30% say this will definitely happen; 56% say it probably will). And roughly two-thirds (65%) expect that a Hispanic person will lead the country sometime in the next 30 years (13% definitely; 53% probably).

Expectations of a female president are broadly shared. Eight-in-ten or more men and women, whites, blacks and Hispanics, and Republicans and Democrats predict there will be a woman in the White House by 2050. Roughly two-thirds of whites (67%) and Hispanics (65%) and 55% of blacks say that a Hispanic person will be president; Hispanics (23%) are more likely than whites (11%) or blacks (7%) to say this will definitely happen.

Few Americans predict a higher standard of living for families, older adults or children in 2050

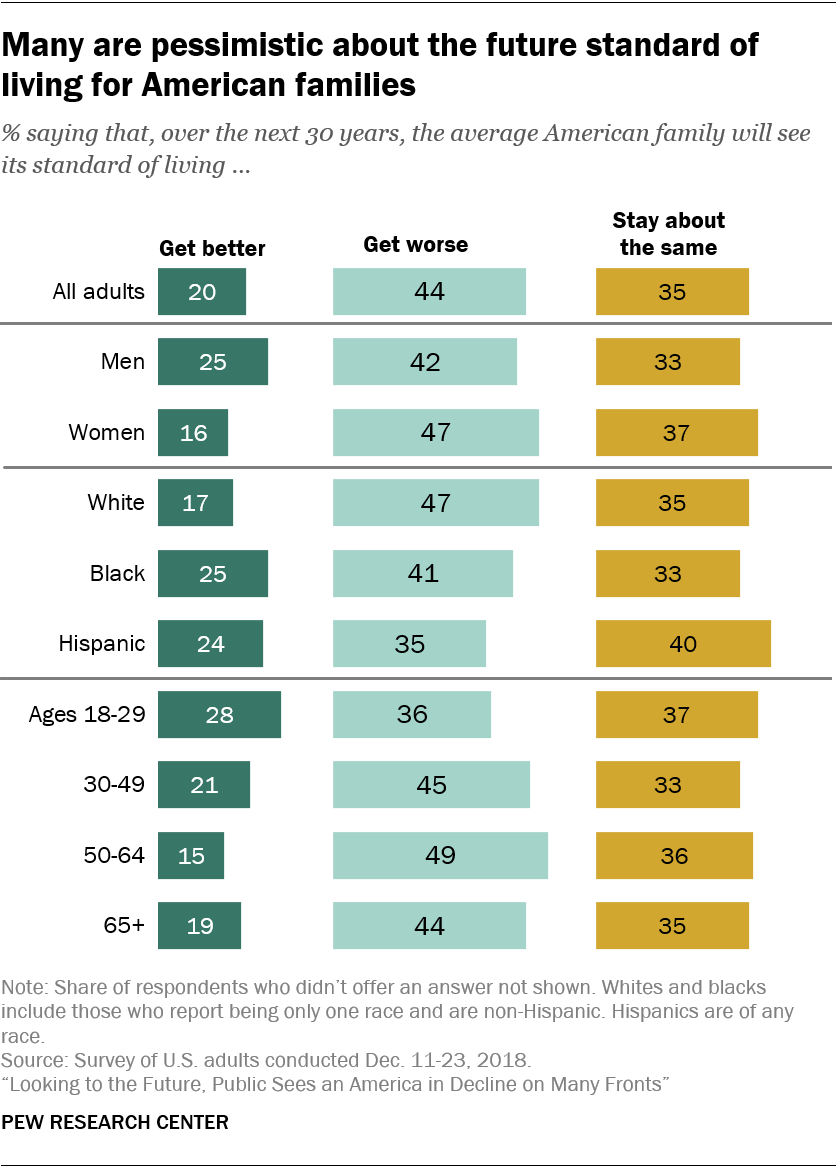

When Americans predict what the economic circumstances of the average family will be in 2050, they do so with more trepidation than hope. More than four-in-ten (44%) predict that the average family’s standard of living will get worse over the next 30 years, roughly double the share who expect that families will live better in 2050 than they do today. About a third (35%) predict no real change.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to think the average family’s standard of living will erode over the next 30 years. Some 47% of women are pessimistic about the economic future of families, while only 16% are optimistic. By contrast, 42% of men expect the typical family’s standard of living to be worse, while a quarter say it will improve.

While comparatively few Americans predict a better standard of living for families, minorities are somewhat more likely than whites to be optimistic. About a quarter of blacks (25%) and Hispanics (24%) say the average family’s standard of living will be higher in 2050 than it is today, compared with 17% of whites. And while nearly half of all whites predict things will get worse for families, only about a third of Hispanics (35%) are as pessimistic.

When younger adults look ahead to 2050, they are more likely than their older counterparts to see a brighter future for America’s families. About three-in-ten (28%) of adults ages 18 to 29 but 19% of those age 30 and older say the average family’s standard of living will get better over the next three decades. Still, about a third (36%) of 18- to 29-year-olds predict harder times ahead for families compared with 46% of those ages 30 and older.

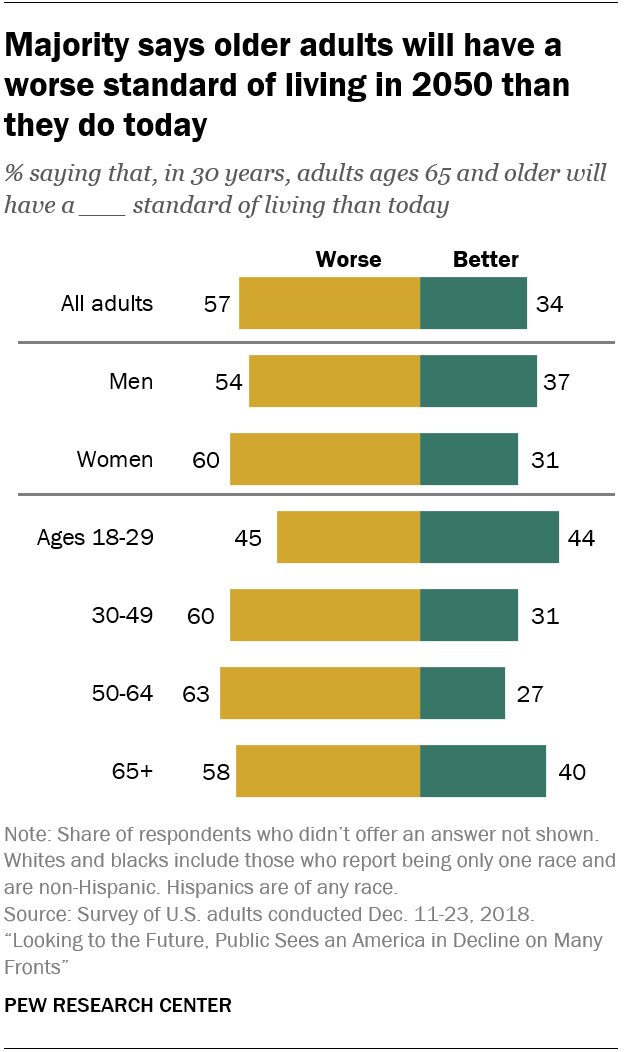

The public also is broadly pessimistic about the economic fortunes of older Americans during the next 30 years. A 57% majority says adults ages 65 and older will have a worse standard of living in 2050 than today. The public is somewhat less negative about the economic prospects of children; half say children will have a worse standard of living in 30 years than they do today, while 42% predict that their standard of living will improve.

When it comes to the future economic prospects of older adults, young adults and those ages 65 and older are more upbeat than their middle-aged counterparts: 44% of those ages 18 to 29 and 40% of those 65 and older say older adults will have a better standard of living 30 years from now, compared with 31% of those ages 30 to 49 and 27% of those 50 to 64.

The public does see at least one bright spot ahead for older Americans. About six-in-ten (59%) expect that a cure for Alzheimer’s disease will definitely or probably be found by 2050. Adults ages 65 and older are among the most optimistic about this: 70% expect an Alzheimer’s cure in the next 30 years. By contrast, about half (53%) of those younger than age 30 predict such a breakthrough.

However, the public is broadly pessimistic about the trajectory of health care costs over the next 30 years. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) predict health care will be less affordable in 2050 than it is today, a view shared across most demographic groups.