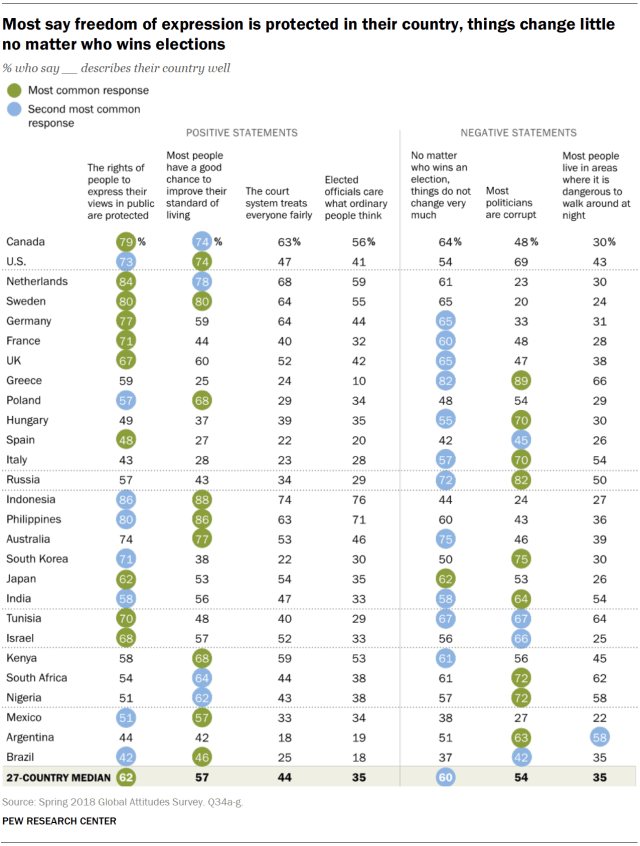

A median of 62% say their country is one where the rights of people to express their views in public are protected. When asked about a number of different statements that describe their country, this ranks as one of the first or second most cited in two-thirds of the countries surveyed.

Publics are also optimistic that most people have a good chance to improve their standard of living: A median of 57% say this is feasible in their countries. Most also feel relatively safe; in a majority of countries, only small shares of the public say most people in their country live in areas where it is dangerous to walk around at night.

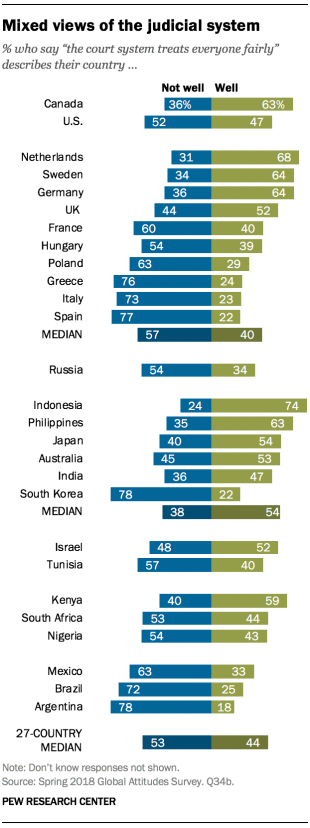

When it comes to political institutions, however, publics are more critical. A median of six-in-ten think no matter who wins an election, things do not change very much. This sentiment is particularly prevalent in Europe; seven of the 10 European countries surveyed say this describes their country more than most other statements presented to them. People are somewhat more critical of their courts: A median of 44% share the opinion that the court system in their country treats everyone fairly, whereas a median of 53% say this does not describe their country well.

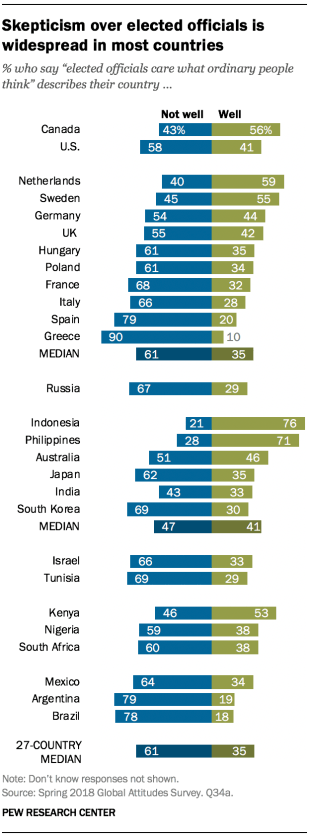

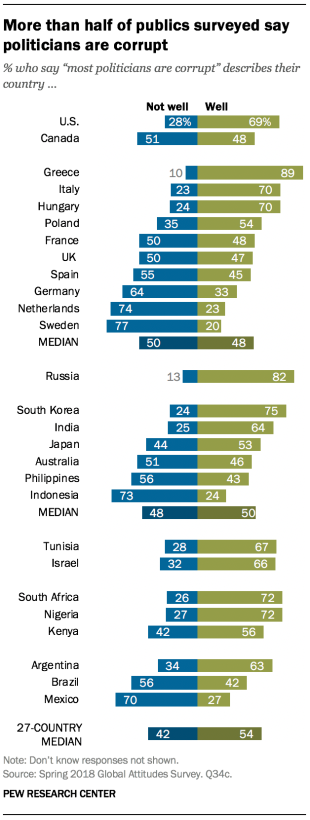

People are also skeptical of their politicians. Across the 27 countries surveyed, 54% think most politicians in their country are corrupt. And only 35% agree that elected officials care what ordinary people think.

By and large, supporters of the governing party or coalition are more inclined to say elected officials care what ordinary people think, freedom of expression is protected, and most people can better their standard of living. Those who support the governing party or coalition are also less likely to describe politicians in their country as corrupt in seven countries.

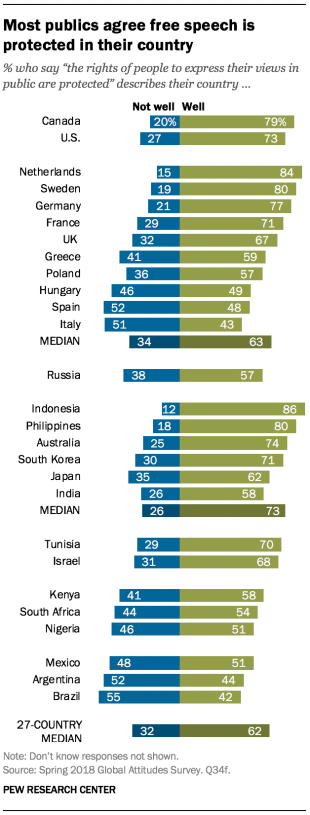

Most believe their right to free speech is protected

A 27-country median of 62% say their country protects freedom of expression. This sense is somewhat more prevalent in advanced than emerging economies (a median of 68% vs. 58%, respectively).

Across the North American and European nations surveyed, around half or more in most countries say their nation is one in which people can express their views in public. The sense that freedom of speech is protected is also widespread in the two Middle Eastern countries surveyed, as well as across the Asia-Pacific region. But, across the 27 nations, few say this describes their country very well.

Only in Brazil, Spain, Argentina, Italy and Mexico do about half or more say this statement does not describe their country well. In Brazil, roughly four-in-ten (39%) say this does not describe their country well at all.

Across most European countries surveyed, those who have favorable opinions of populist parties are significantly less likely to feel their country is one in which freedom of expression is protected. Take Sweden as an example: Those who have a favorable opinion of the Sweden Democrats are 30 percentage points less likely to think free speech is protected in their country than those who do not favor this party.

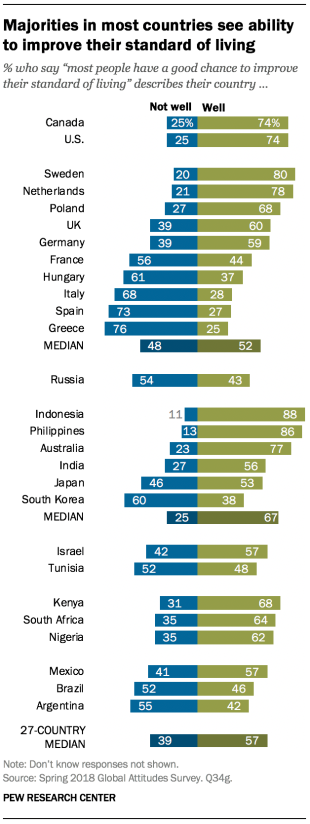

Most say they have the ability to improve their standard of living

Publics generally say their countries are ones in which there are opportunities to improve living standards. A median of 57% across the 27 nations surveyed agree most people have a good chance to improve their own standard of living, including majorities in 16 of the 27 nations surveyed. This sentiment is slightly more widespread in the nine emerging economies surveyed (median of 62%) than in the 18 advanced economies (55%).

Filipinos, South Africans and Nigerians are especially likely to describe their countries as ones in which people can improve their economic situation; about four-in-ten or more in each country say this describes their country very well.

But in Italy, Spain and Greece, only about one-quarter of people say their country is one in which it is possible to improve their standard of living, with around four-in-ten in Spain (41%) saying this does not describe their country well at all.

In all of the nations surveyed, the belief that people can get ahead economically is closely related to views about whether their country’s economy has improved over the past 20 years. Those who think the economic situation has gotten better are more likely to say most people in their country have the opportunity to advance their standard of living. For example, 69% of French people who think the economic situation today is better for the average person than it was in the past also say it is possible to improve their standard of living, compared with 33% among those who say the economic situation today is worse than it was 20 years ago. In most countries polled, people with positive assessments of their country’s current economic situation are also more likely to say that most people have a good chance to advance their standard of living.

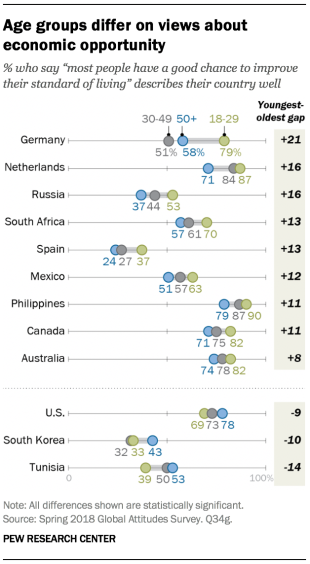

In nine of the 27 nations, those ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those ages 50 and older to say people can improve their standard of living. For example, younger Germans are 21 percentage points more likely than older Germans to describe their country as a place where most have opportunities to better their standard of living.

Three countries stand out for the relative pessimism of the younger generation. In the U.S., South Korea and Tunisia, those under 30 are less likely than the oldest cohort to say their country is one in which people can improve their economic situation. In Tunisia, for example, 53% of those ages 50 and older are positive about the potential for people in their country to improve their standard of living compared with 39% of those 18 to 29.

Global publics divided on whether court system treats everyone fairly

A 27-nation median of 44% say the statement “the court system treats everyone fairly” describes their country well, while a median of 53% say it does not. And opinions about a country’s court system vary little across the advanced and emerging economies surveyed.

Indonesians are particularly likely to say their courts are impartial; around three-quarters say the court system treats everyone fairly (74%), including around four-in-ten (38%) who say this describes their country very well. Views on the impartiality of the courts are also shared in the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, Canada, the Philippines and Kenya, where roughly six-in-ten or more say this describes their country well.

Publics in Italy, Spain, South Korea and Argentina are less confident in the fairness of their court systems: Only around one-in-five in each of these nations say the courts treat everyone fairly. Roughly half or more in Argentina, Brazil, Spain and Mexico say this statement does not describe their country well at all.

Most publics do not feel elected officials care what ordinary people think

In 20 of the 27 countries surveyed, around half or more say that the statement “elected officials care what ordinary people think” does not describe their country well.

Nine-in-ten Greeks agree the statement does not describe their country well, and upwards of around eight-in-ten say the same in Brazil, Spain and Argentina. Publics in these four countries also have high percentages who feel strongly about this: 62% of Brazilians, 57% of Greeks, 54% of Argentines and 48% of Spaniards say the statement does not describe their country well at all.

Among the minority of publics who do agree elected officials in their country care what ordinary people think, Indonesia and the Philippines stand out. In both countries, around seven-in-ten or more describe their country as one in which elected officials care about the people, including three-in-ten or more in each who say this describes their country very well.

Publics in the Netherlands, Canada, Sweden and Kenya are also somewhat sanguine about elected officials caring about the citizens in their country.

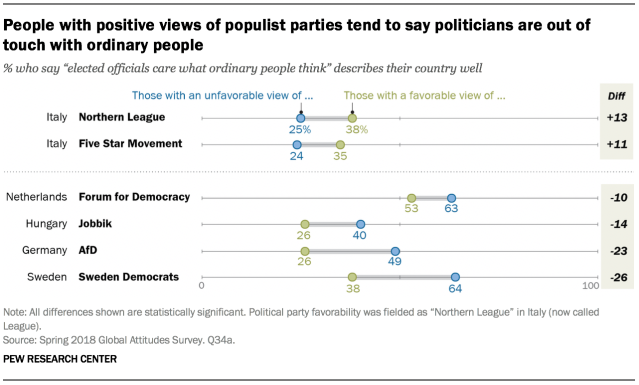

Although populism has myriad definitions, key components of the concept are that “the people” and “the elite” are two antagonistic groups and that the people’s will should provide the main source of government legitimacy. And, in four countries – the Netherlands, Hungary, Germany and Sweden – people with favorable views of populist parties are indeed less likely to say elected officials care what ordinary people think than those who view these parties unfavorably. For example, those with favorable views of the Sweden Democrats are 26 percentage points less likely than Swedes with unfavorable opinions of the party to describe elected officials as caring about ordinary people.

Many describe their country’s politicians as corrupt

In 18 of the 27 countries surveyed, around half or more say their country can be described as one in which most politicians are corrupt.

In many European nations, roughly half or more say they live in a country in which the statement “most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well. Majorities also share this opinion in the U.S., as well as the two Middle Eastern and three sub-Saharan African countries surveyed. Opinion is more divided in the Asia-Pacific region and Latin America.

Greeks are the most likely to describe their politicians as corrupt (89%), while around three-quarters or more in Russia, South Korea, Nigeria and South Africa describe their country in a similar manner.

Publics in Sweden, the Netherlands, Indonesia, Mexico and Germany are the least likely to say their country can be described as one in which most politicians are corrupt.

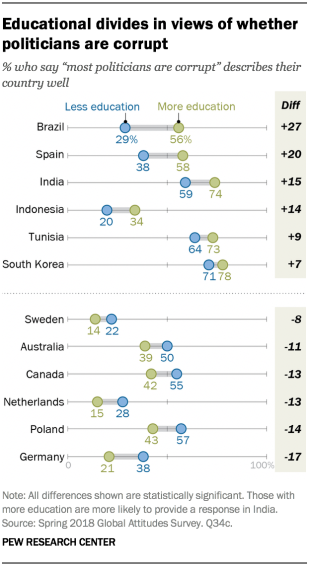

In many of the 27 countries surveyed, there are educational divides on whether most politicians in the country can be described as corrupt. Particularly in emerging and developing economies, people with higher levels of education are more likely to say most politicians are corrupt. For example, Brazilians with more education are 27 percentage points more likely than those with less education to describe politicians in the country as corrupt.

But, in six countries – all of which are advanced economies – the pattern is reversed; people with less education are more likely to describe politicians as corrupt. Take Germany as an example: Germans with less than a postsecondary degree are 17 points more likely to say most politicians in their country are corrupt than Germans with more education.

Those with favorable opinions of populist parties in five European countries (the PVV in the Netherlands, AfD in Germany, Jobbik in Hungary, Sweden Democrats in Sweden and UKIP in the United Kingdom) are more likely than those with unfavorable opinions of these parties to say most politicians in their country are corrupt.

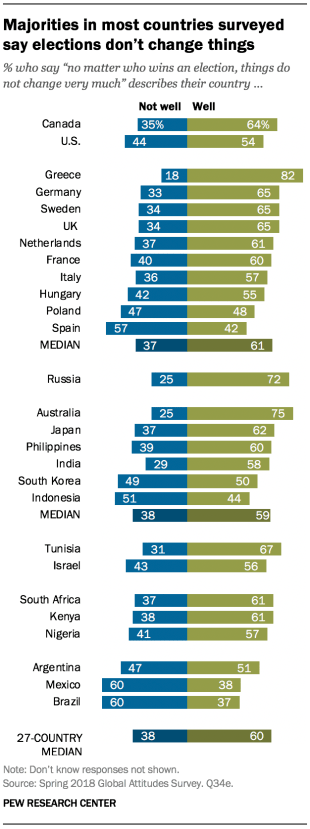

Few think things in their country change much after an election

One of the core tenets of democracy is that, after an election, parties and policies in the country may change. But many global publics say this doesn’t describe what happens in their countries following an election. A 27-country median of 60% say no matter who wins an election, things don’t change very much.

Greeks are the most likely to describe their country as one where things do not change very much no matter who wins an election (82%), followed by Australians (75%), Russians (72%) and Tunisians (67%). And, in Tunisia and Greece, more than half say this statement describes their country very well.

It is worth noting that whether or not things change a lot following an election could be interpreted as either a positive or a negative characteristic of democracy. For some, no change after an election may be a good thing, whereas for others it may be bad.

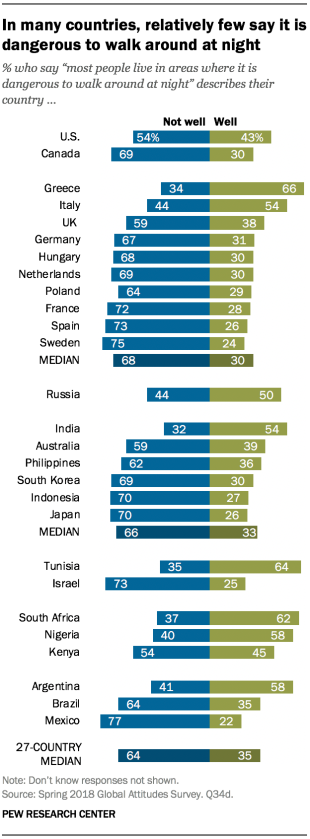

Most say their countries are generally not dangerous for walking around at night

A median of 35% believe most people live in areas where it’s dangerous to walk around at night. But opinion diverges somewhat across advanced and emerging economies. In advanced economies, a median of only 30% say most people live in areas where it is dangerous to walk around at night, compared with a median of 45% across the nine emerging economies surveyed.

Around six-in-ten or more in Greece, Tunisia, South Africa, Nigeria and Argentina describe their country as one in which most people live in areas where it is dangerous to walk around at night, including roughly half or more in Tunisia and South Africa who say this describes their country very well. But, across most European, Asia-Pacific and North American countries surveyed, people largely agree this statement does not describe their country well.

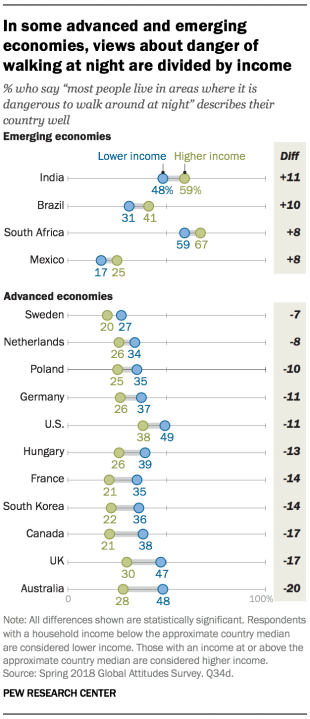

There are also marked differences in people’s assessments based on income levels. In four emerging economies – India, Brazil, South Africa and Mexico – those with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to describe their country as one in which most people live in areas where it is dangerous to walk around at night. In India, though, those with lower incomes are also less likely to answer the question.

In most advanced economies, the pattern reverses. Those with lower incomes are more likely to believe it is dangerous to walk around at night. For example, less affluent Australians are 20 percentage points more likely to say most people live in dangerous areas.

Educational gaps follow a similar pattern. In many advanced economies, those with lower levels of education are somewhat more likely to describe their country as dangerous to walk around in at night. For example, in Germany, there is a 25-point gap between those with lower levels of education and those with a postsecondary degree or above (39% vs. 14%). But, in three of the emerging economies – Brazil, India and Indonesia – those with higher educational attainment are more likely to say many people live in dangerous areas.4

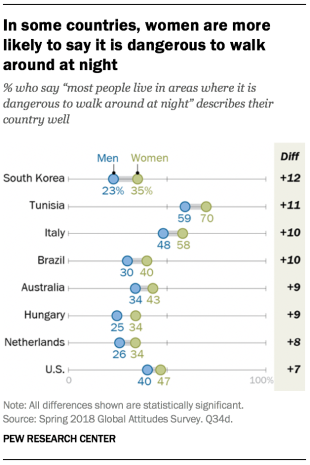

In eight countries, women are more likely than men to describe their country as one in which it is dangerous to walk around at night. In South Korea, for example, women are 12 percentage points more likely than men to express this opinion.