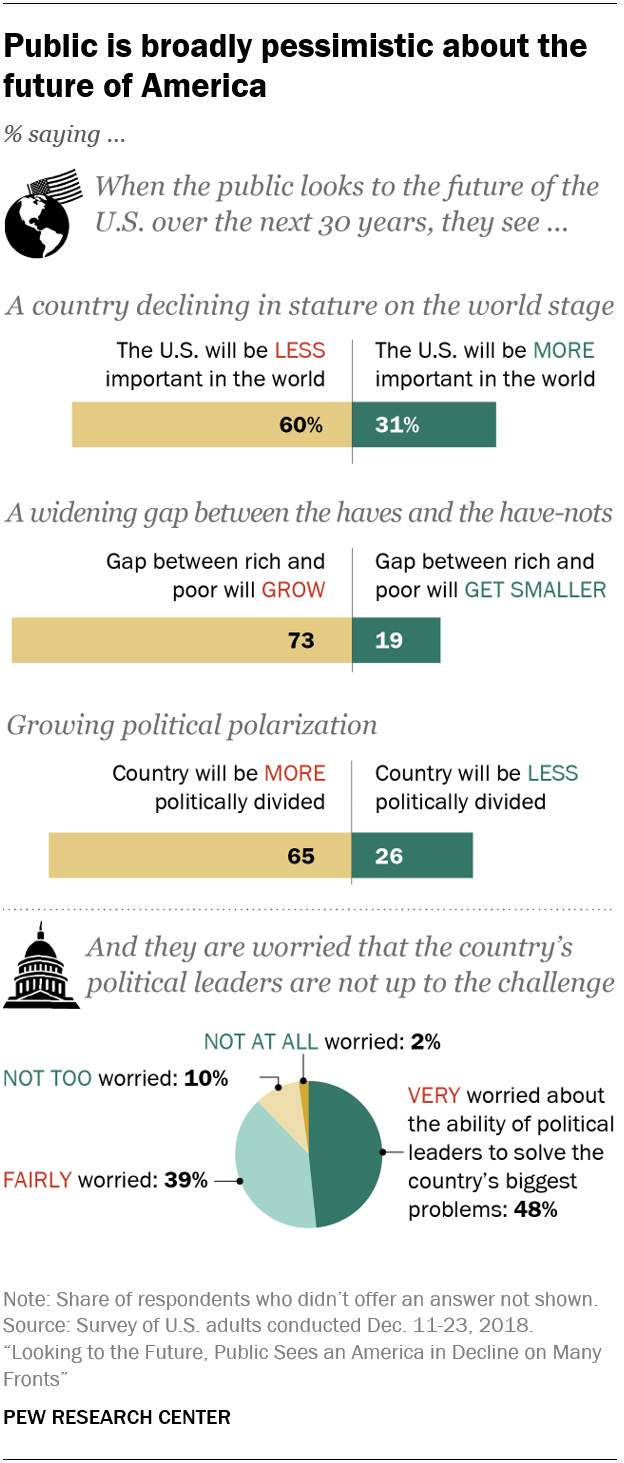

When Americans peer 30 years into the future, they see a country in decline economically, politically and on the world stage. While a narrow majority of the public (56%) say they are at least somewhat optimistic about America’s future, hope gives way to doubt when the focus turns to specific issues.

A new Pew Research Center survey focused on what Americans think the United States will be like in 2050 finds that majorities of Americans foresee a country with a burgeoning national debt, a wider gap between the rich and the poor and a workforce threatened by automation.

Majorities predict that the economy will be weaker, health care will be less affordable, the condition of the environment will be worse and older Americans will have a harder time making ends meet than they do now. Also predicted: a terrorist attack as bad as or worse than 9/11 sometime over the next 30 years.

These grim predictions mirror, in part, the public’s sour mood about the current state of the country. The share of Americans who are dissatisfied with the way things are going in the country – seven-in-ten in January of 2019 – is higher now than at any time in the past year.

The view of the U.S. in 2050 that the public sees in its crystal ball includes major changes in the country’s political leadership. Nearly nine-in-ten predict that a woman will be elected president, and roughly two-thirds (65%) say the same about a Hispanic person. And, on a decidedly optimistic note, more than half expect a cure for Alzheimer’s disease by 2050.

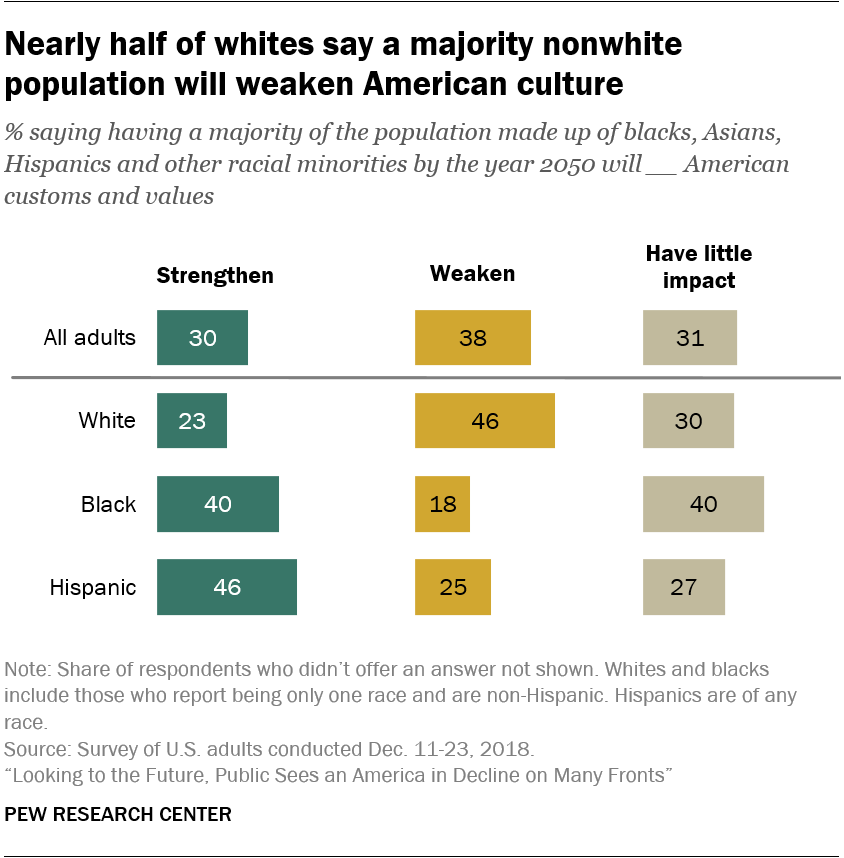

The public also has a somewhat more positive view – or at least a more benign one – of some current demographic trends that will shape the country’s future. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that, by 2050, blacks, Hispanics, Asians and other minorities will constitute a majority of the population. About four-in-ten Americans (42%) say this shift will be neither good nor bad for the country while 35% believe a majority-minority population will be a good thing, and 23% say it will be bad.

These views differ significantly by race and ethnicity. Whites are about twice as likely as blacks or Hispanics to view this change negatively (28% of whites vs. 13% of blacks and 12% of Hispanics). And, when asked about the consequences of an increasingly diverse America, nearly half of whites (46%) but only a quarter of Hispanics and 18% of blacks say a majority-minority country would weaken American customs and values.

The public views another projected change in the demographic contours of America more ominously. By 2050, people ages 65 and older are predicted to outnumber those younger than 18, a change that a 56% majority of all adults say will be bad for the country.

In the face of these problems and threats, the majority of Americans have little confidence that the federal government and their elected officials are up to meeting the major challenges that lie ahead. More than eight-in-ten say they are worried about the way the government in Washington works, including 49% who are very worried. A similar share worries about the ability of political leaders to solve the nation’s biggest problems, with 48% saying they are very worried about this. And, when asked what impact the federal government will have on finding solutions to the country’s future problems, more say Washington will have a negative impact than a positive one (55% vs. 44%).

Instead, large majorities of Americans look to science and technology as well as to the education system to solve future problems: 87% say science and technology will have a very or somewhat positive impact in solving the nation’s problems, and roughly three-quarters say the same about public K-12 schools (77%) and colleges and universities (74%). Even so, roughly three-quarters (77%) worry about the ability of public schools to provide a quality education to tomorrow’s students, and more expect the quality of these schools to get worse, not better, by 2050. And only about a third (34%) of the country rates increased spending on scientific research as a top policy priority.

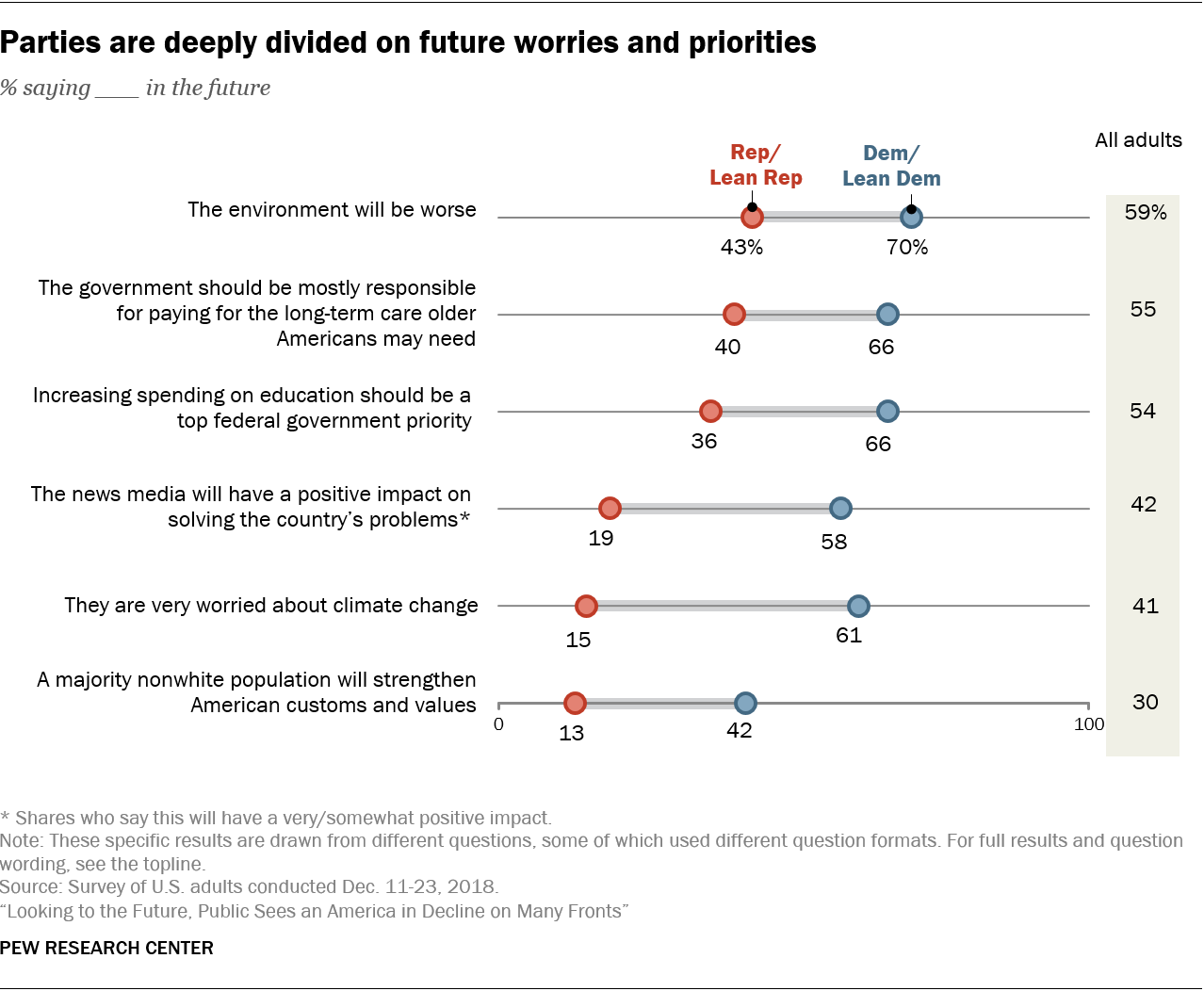

Underlying many of these and other findings are deep divisions along the traditional fault lines of American life, including race, age and education. However, among the more striking differences found in this survey are those between Republicans and Democrats. Taken together, the size and frequency of these differences underscore the extent to which partisan polarization underpins not just the current political climate but views of the future as well.

Across a range of issues, the difference between partisans is not merely apparent, but conspicuously large. Despite shared concern about the future quality of the nation’s public schools, about two-thirds of Democrats and those who lean Democratic (66%), but only 36% of Republicans and Republican leaners, rate increased spending on education as a top federal government priority. About six-in-ten Democrats (58%) but only 19% of Republicans say the news media will have a positive impact on solving the country’s future problems. About four-in-ten Democrats (42%) say a majority-nonwhite population will strengthen American customs and values, a view expressed by only 13% of Republicans. Similarly, about six-in-ten Democrats (61%) but just a third of Republicans consider the growth of interracial marriage to be a good thing for society. Partisan gaps on future priorities reflect similar gaps in current policy priorities. Recent research has shown that Republicans and Democrats have moved farther apart in recent decades in their views on what the top priorities for Congress and the president should be.

Partisan differences are particularly large on issues related to the environment. About six-in-ten Democrats (61%) but only 15% of Republicans say they are very worried about climate change. An even larger share of Democrats (70%) predict the condition of the environment will get worse in the next 30 years, while 43% of Republicans agree.

Even their top priorities for the future are, in many instances, strikingly different. Among all adults, health care and increased spending on education topped the list of policies that the public believes the federal government should enact to improve the quality of life for future generations. Yet the top-three Republican priorities – reducing the number of undocumented immigrants, cutting the national debt and avoiding tax increases – don’t even appear among the Democrats’ highest five priorities.

Conversely, three of the five Democratic priorities – dealing with climate change, reducing the gap between rich and poor, and increasing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid – are absent from the GOP’s top-five list. Providing high-quality health care and increasing spending on education are top priorities for each party, though larger shares of Democrats than Republicans rank these issues as top priorities.

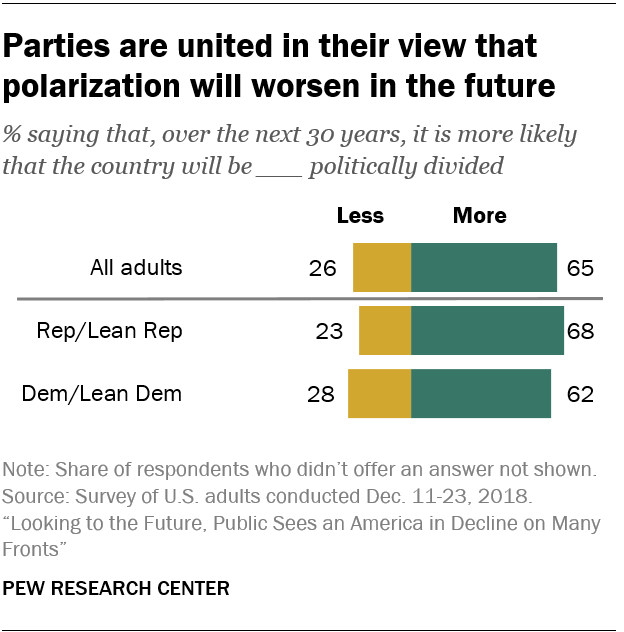

It is perhaps fitting that, while the two parties hold similar views on a number of issues, one area of agreement stands out: Majorities of both parties agree that the country will be more politically divided in 2050 than it is today.

The nationally representative survey of 2,524 adults was conducted online Dec. 11-23, 2018, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel.1 Among the other key findings:

Majorities of Americans predict a tougher time financially for older adults in 2050

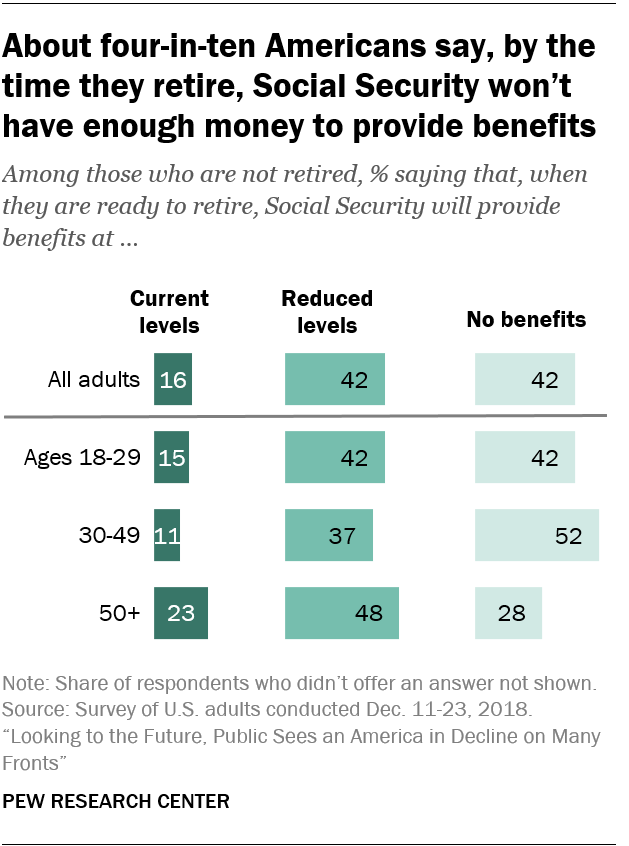

About seven-in-ten Americans (72%) expect older adults will be less prepared financially for retirement in 2050 than they are today. An even larger share (83%) predict that most people will have to work into their 70s in order to afford to retire. And the public’s forecast for the future of the Social Security system is decidedly grim.

Among those who are not yet retired, 42% expect to receive no Social Security benefits when they leave the workforce, and another 42% anticipate that benefits will be reduced from what they are today.

Adults younger than 50 are particularly doubtful that Social Security will be there when they leave the workforce: 48% expect to receive no Social Security benefits when they retire. By contrast, 28% of those who are 50 or older are similarly pessimistic. But even among this older group, only about a quarter (23%) expect to receive Social Security benefits at current levels. These findings reflect a long-standing skepticism – particularly among young adults – about the long-term solvency of the Social Security system.

Even as they doubt the long-term financial viability of the Social Security system, most Americans reject reducing benefits. Only a quarter believe that some reductions in benefits for future retirees will need to be made to shore up the system’s finances, while about three times as many say benefits should not be reduced in any way.

Few Americans predict a better standard of living for families in 2050

More than four-in-ten Americans (44%) predict that the average family’s standard of living will get worse rather than better over the next 30 years. That’s roughly double the share (20%) who expect families to fare better financially in the future than they do today; 35% predict no real change.

When it comes to prospects for children, half of the public says children will have a worse standard of living in 30 years than they do today, while 42% predict that they will be better off. Men are more likely than women to say children’s standard of living will be higher in 30 years than it is today (47% vs. 36%), while those who do not have children in the home are somewhat more pessimistic about this than those who do (52% vs. 44% say children will have a worse standard of living).

Large majority says health care for all would benefit future generations

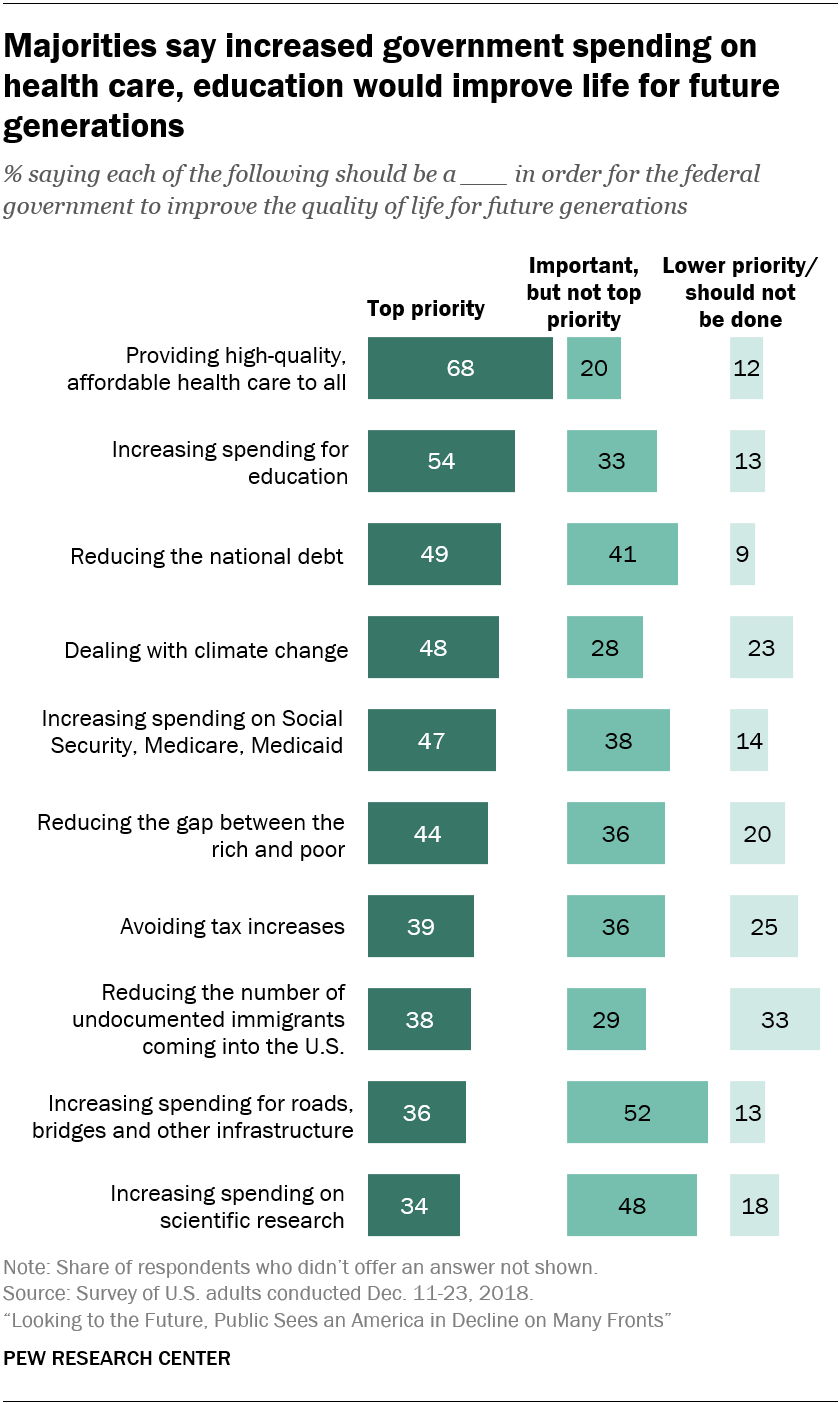

When asked what the federal government should do to improve the quality of life for future generations, providing high-quality, affordable health care to all Americans stands out as the most popular policy prescription. Roughly two-thirds (68%) say this should be a top priority for government in the future.

Increased spending on education is somewhat less popular; 54% say more money for schools should be a top federal government priority in order to improve life for future generations. Slightly fewer say the same about reducing the national debt or dealing with climate change (49% and 48%, respectively, say each should be a top priority). A larger share of Republicans than Democrats prioritize cutting the debt, while just the opposite is true for climate change.

Increasing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid is viewed as a top priority by 47% of adults, and reducing the gap between rich and poor is seen as such by 44%. Falling further down the list are avoiding tax increases, reducing the number of undocumented immigrants coming into the U.S., increasing spending on infrastructure and more money for scientific research.

Minorities are more optimistic than whites about the country’s future

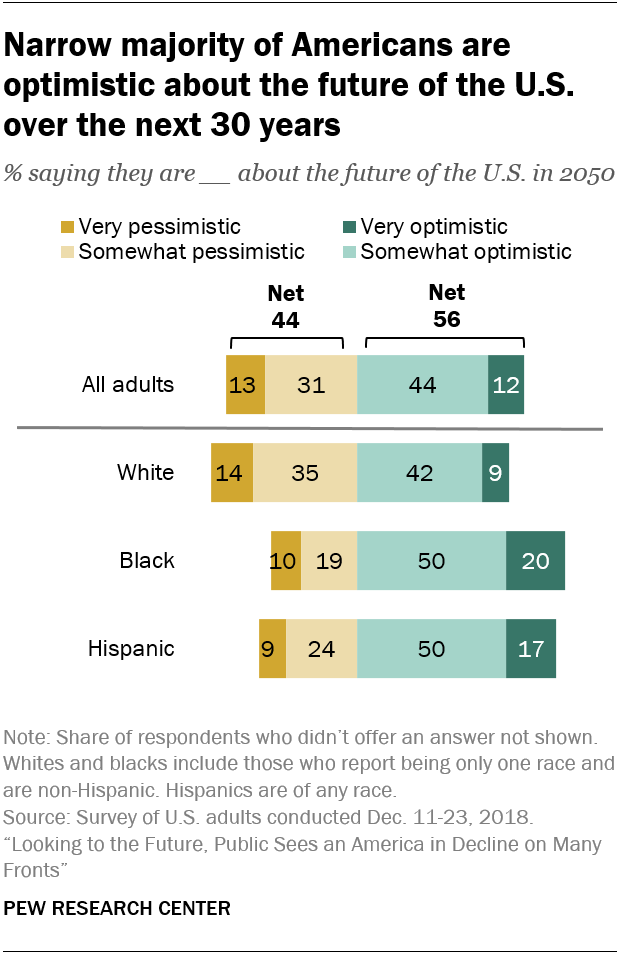

Overall, 56% of all adults say they are either very optimistic (12%) or somewhat optimistic (44%) about the U.S. in 2050. But more than four-in-ten (44%) see the country’s future more darkly, including 13% who say they are very pessimistic and 31% who are somewhat pessimistic about America in 30 years.

Black and Hispanic adults are among the most optimistic about the country’s future. Seven-in-ten blacks and two-thirds of Hispanics feel hopeful about America’s future. In contrast, about half of all whites (51%) are as confident. High school graduates and those with less education also are somewhat more positive about the country’s prospects than are college graduates (60% vs. 53%).

Unlike the wide partisan differences seen elsewhere in this survey, Democrats and Republicans are about equally optimistic when it comes to these broad predictions about America’s future.

The racial pattern switches when Americans are asked about the future of race relations over the next 30 years. Slightly more than half of all whites (54%) but 43% of blacks and 45% of Hispanics say relations will get better. Overall, the country is divided on the future of race relations: About half (51%) say they will improve, while 40% predict they will get worse.

Most Americans worry about the country’s moral values; half say religion will become less important

Roughly four-in-ten Americans (43%) say they are very worried about the nation’s morals, while another 34% are fairly worried. For Republicans, the country’s moral health is a major concern: Roughly half (49%) say, when they think about the country’s future, they are very worried about the moral values of Americans. Only about a third of Democrats (36%) are equally worried. Women are more concerned about the country’s morals than men (46% vs. 38%), while older Americans are more worried than those younger than 50 (49% vs. 37%).

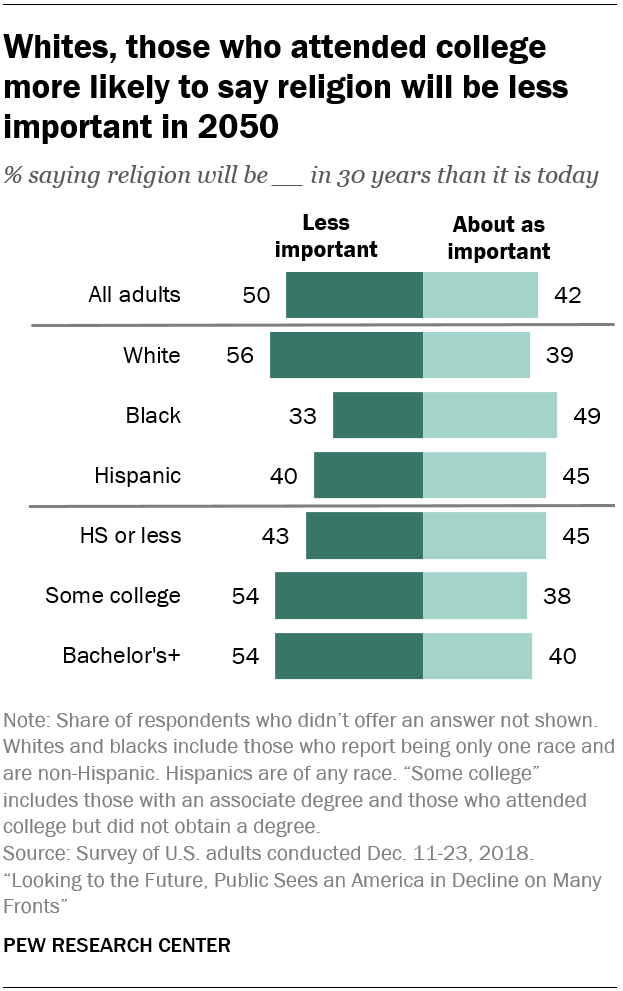

The public is divided over whether religion will become less important over the next 30 years than it is now. Half say religion will lose importance, while 42% say it will remain unchanged (respondents were not given the option of saying religion will be more important).

A majority of whites (56%) but only a third of blacks and four-in-ten Hispanics say the importance of religion will decline over the next 30 years. Adults with more formal education are more likely to see religion in eclipse than those with less: 54% of all college graduates but 43% of those with a high school degree or less education predict the declining importance of religion.

Among religious groups, roughly equal shares of white evangelicals (52%), white mainline Protestants (51%) and white Catholics (54%) say religion will be less important in the future – a view held by a similar share (59%) of those who are atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular.

Older adults, those with less education more negative about the impact of automation

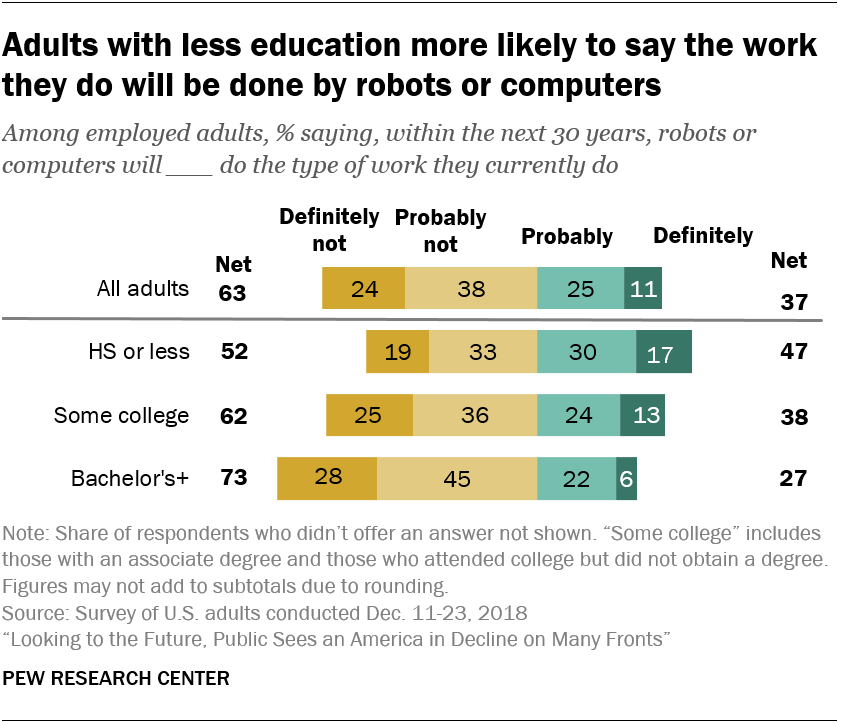

While only 37% of all currently employed Americans personally see automation as a direct threat to their current occupation, less well-educated workers are likelier than those with more formal schooling to say the type of work they do will be done by robots or computers in the future. About half (47%) of those with a high school diploma or less education say this change will occur compared with 38% of those with some college experience and 27% of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

Most Americans agree that the workplaces of the future will be heavily automated. About eight-in-ten (82%) predict that robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans – a possibility that many adults with less education view with suspicion, if not outright dread. Among those who say robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans, about eight-in-ten of those with a high school diploma or less education say this would be a bad thing for the country (39% say it would be very bad; 39% say it would be somewhat bad). Those with a bachelor’s degree or more education are less fearful: Roughly six-in-ten say an automated workplace would be very (13%) or somewhat bad (45%).

Regardless of educational background, most Americans predict that automation in the workplace will increase inequality between the rich and the poor and will not result in new, better-paying jobs.

Who will pay – and who should pay – for long-term eldercare in the future?

A slim majority of Americans (55%) say that government should be mostly responsible for paying for long-term care for older adults who need assistance in the future. But when asked who will be responsible for paying for this care in the future, only about half that share (28%) say the financial burden will fall on the government. Instead, about seven-in-ten predict that family members (35%) or older adults themselves (36%) will bear these costs.

Similar shares of most key demographic groups agree about who will pay the bills for long-term care in the future. But these groups often differ about who should be primarily responsible for the costs of this care. Two-thirds of blacks and Hispanics (67%) say government should be mostly responsible for paying for long-term care for older adults, while about half of whites (51%) agree. Similarly, two-thirds of adults ages 50 to 64 say government should be mostly responsible for this care compared with about half of all other age groups, including those 65 and older. In addition, two-thirds of Americans with family incomes under $30,000 look to government to cover the cost, compared with about half of those with higher incomes.

Democrats see a bigger role than Republicans for the government in paying for long-term elder care (66% vs. 40%). On the other hand, Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to believe older adults themselves should be primarily responsible for paying for their care (40% vs. 21%). Relatively few Democrats (11%) or Republicans (18%) say the responsibility should fall mainly to family members.

Predictions about the future of marriage, divorce and childbearing differ by race

Overall, about half of adults (53%) say that, by 2050, people will be less likely to get married than they are today. Very few (7%) predict that people will be more likely to marry in the future, and 39% say things will stay about the same. Whites and Hispanics are much more likely than blacks to predict lower marriage rates in the future – 56% of whites and 53% of Hispanics say people will be less likely to marry compared with 34% of blacks. Blacks are the only group in which a majority say marriage rates will stay the same or increase. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, blacks are significantly less likely than whites or Hispanics to be married. Among those ages 18 and older, 31% of blacks were married in 2017 compared with 46% of Hispanics and 54% of whites.2

Predictions about the future of divorce reveal a somewhat different pattern. More than six-in-ten whites (64%) but half of blacks and 42% of Hispanics expect people will be about as likely to get divorced in 2050 as they are today. In this regard, Hispanics are more pessimistic than whites about the future state of marriage: 37% predict that people will be more likely to divorce in the future, compared with 27% of whites and 30% of blacks.

More than four-in-ten Americans (46%) expect that, by 2050, people will be less likely to have children than they are now. A similar share (43%) think people will be about as likely to have children, while just one-in-ten expect people to be more likely to have children in the future. Young adults are more likely than older Americans to say this is the case. Even so, only 18% of those ages 18 to 29 say they expect that people in 2050 will be more likely to have children, compared with 9% of adults 30 to 49 and 7% of those ages 50 and older.