Political scientists often measure the concept of tolerance with a hypothetical question: How would you feel if your child married someone with a different background or identity than your own? For example, political scientists have found that a growing share of Americans do not want their child to marry someone who supports a different political party than they do.

Yet some academics have found that survey questions about hypothetical partisan marriages may conflate two things: partisan hostility and a simple distaste for politics. In an experiment, political scientist Samara Klar and her colleagues found that survey respondents’ opposition to a potential marriage falls sharply if their child’s hypothetical spouse supports a particular political party but also is largely apolitical or rarely talks about politics.

Here at Pew Research Center, we’ve used hypothetical questions to measure religious tolerance. For example, we have asked survey respondents in Europe whether they would accept people who are Muslim or Jewish as members of their family. But similar to the partisanship experiment, respondents’ answers may capture a general distaste for religion rather than intolerance for particular religious groups.

To test this, we ran a survey experiment on religious tolerance in Australia using a nationally representative panel of adults. We divided people into three groups and asked them slightly different questions to see what difference the changes in wording made. Below, we explore the results of this experiment.

How we did this experiment

We randomly assigned 2,021 Australian survey respondents to three groups:

- In the base group, we asked how they would feel if they had a son or daughter who married someone who is Muslim, Jewish or Christian, randomizing the order of the three faiths.

- In the practicing group, we asked about the same religions but specified that the hypothetical spouse is a practicing member of each religious group.

- In the nonpracticing group, we asked how they would feel if their child married a nonpracticing member of each religious group.

We asked every survey respondent about all three religious groups, always using the same wording. No individual respondent was asked to compare, say, “a practicing Muslim” with “a Christian” or “a nonpracticing Jew.”

Across all three experimental groups, we randomized the order of the religious groups to make sure that the experiment tested only the differences in question wording.

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

How do people feel about these hypothetical marriages?

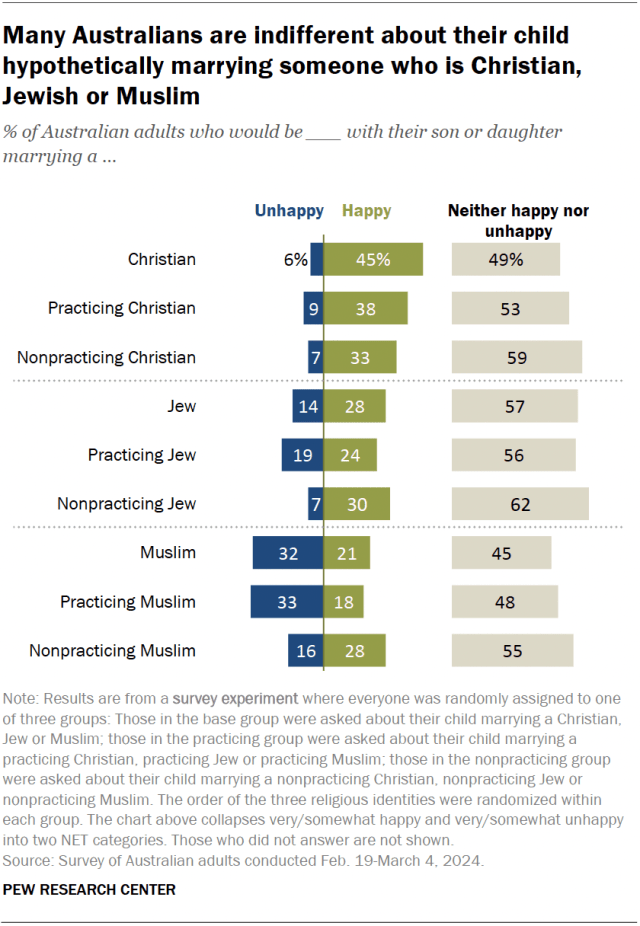

Many Australians express no strong preference about the religion of their child’s hypothetical spouse. Between 45% and 62% of respondents say they would be “neither happy nor unhappy” about their son or daughter marrying a Christian, Muslim or Jew, regardless of the spouse’s religious affiliation or level of practice.

But there are some broad patterns in Australians’ responses. When we didn’t specify a level of religious practice – as was the case in the base group – more respondents say they would be unhappy to have their child marry a Muslim (32%) than say they would be unhappy if their child married either a Jew (14%) or a Christian (6%).

However, there is no statistically significant difference in levels of unhappiness between the base group and the practicing group for Muslims. The share of respondents who would be unhappy if their child married “a practicing Muslim” (33%) is nearly identical to the share who would be unhappy if their child married “a Muslim” (32%).

The same is true when respondents were asked about their child marrying a Christian. Similar shares expressed unhappiness with their child marrying “a practicing Christian” (9%) or “a Christian” (6%). On the other hand, slightly more respondents say they would be unhappy with their child marrying “a practicing Jew” (19%) than “a Jew” (14%).

There are also some significant differences between the base group and the nonpracticing group, particularly when we asked about Muslims and Jews:

- Fewer respondents would be unhappy with their child marrying “a nonpracticing Muslim” (16%) than “a Muslim” (32%).

- Fewer would be unhappy with a marriage to “a nonpracticing Jew” (7%) than to “a Jew” (14%).

- Nearly equal shares say they would be unhappy with a marriage to “a nonpracticing Christian” (7%) and to “a Christian” (6%).

From these results, it appears that asking Australians a hypothetical question about marriage to “a Muslim” is effectively the same as asking about a practicing Muslim, and results are somewhat similar when it comes to a Jew and a practicing Jew.

In both cases, Australians would respond with less unhappiness if the survey question specified that the hypothetical spouse was a nonpracticing Muslim or a nonpracticing Jew.

How do Christians respond?

Does how unhappy a person would be about their child marrying a Muslim, Jew or Christian depend at all on that person’s own religion? Since Christianity is the most common religion in Australia, do these findings primarily reflect the attitudes of Australian Christians toward religious intermarriage?

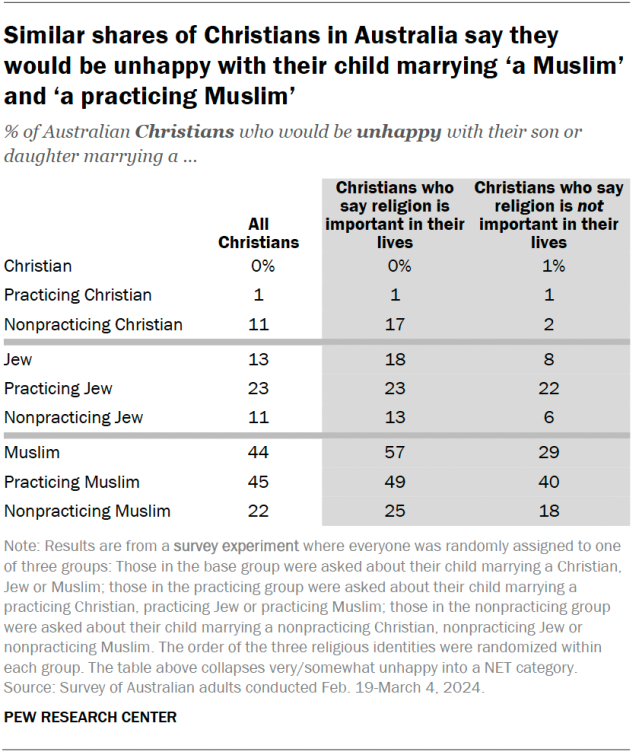

To explore this, we looked at the results of the experiment solely among the survey’s 841 Christian respondents. We find:

- There is no significant difference between the way Christians answer the questions about marriage to a Muslim and a practicing Muslim. But their unhappiness with those hypothetical matches is higher than it would be for a nonpracticing Muslim. It is also higher than for any of the other faiths and practice levels we tested.

- Christian respondents express essentially the same level of comfort with marriage to a Christian (0% unhappy) as with marriage to a practicing Christian (1% unhappy). About one-in-ten (11%) say they would be unhappy with a nonpracticing Christian.

- More Christian respondents say they would be unhappy with a son-in-law or daughter-in-law who is a practicing Jew (23%) than a nonpracticing Jew (11%). But attitudes toward a hypothetical marriage to a nonpracticing Jew and simply “a Jew” – with no level of practice specified – are essentially the same (11% and 13% unhappy, respectively). This suggests that Christian respondents generally think of Jews as nonpracticing.

The survey experiment also reveals differences between Christians who say religion is important in their own lives and Christians who don’t. Christians who view religion as important are more likely than those who view religion as unimportant to express unhappiness with their child marrying “a nonpracticing Christian,” “a Jew,” “a nonpracticing Jew” or “a Muslim.”

How do religiously unaffiliated people respond?

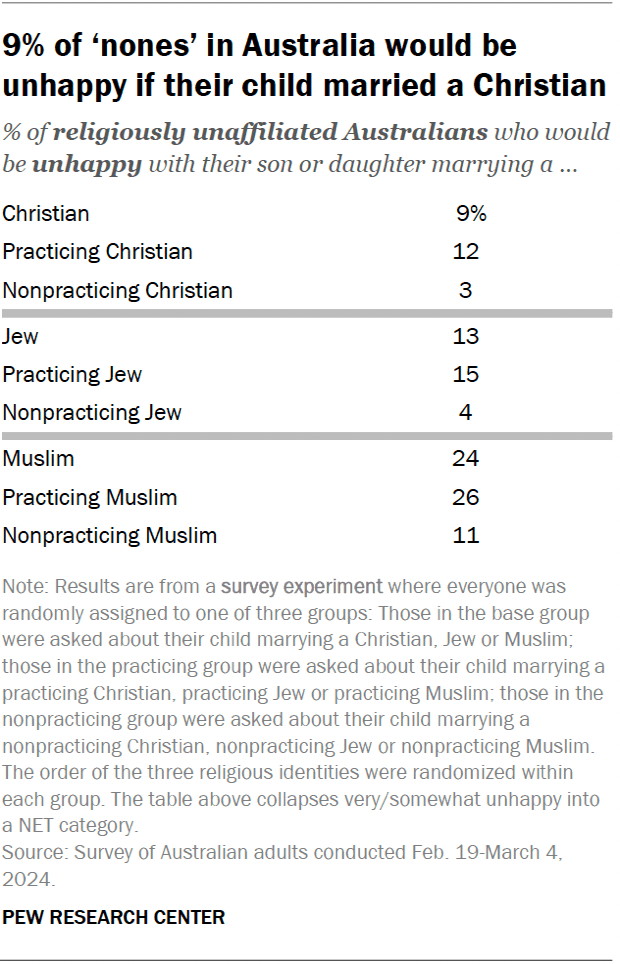

The second largest religious category in Australia, after Christians, is people who do not identify with any religion. Looking solely at unaffiliated respondents, or “nones,” we find:

- More “nones” would be unhappy with their child marrying a Muslim than with their child marrying a Christian, regardless of whether their level of practice is specified.

- “Nones” express relatively lower levels of unhappiness when their hypothetical son- or daughter-in-law is described as nonpracticing, regardless of religious identification.

- Since levels of unhappiness among “nones” are similar when comparing the base and practicing groups in each faith, we can infer that “nones” treat references to a Muslim, Jew or Christian as though the person practices that particular religion.

What do the results of this experiment mean for measuring tolerance?

The experiment’s results suggest that when survey questions mention a hypothetical person’s religion, respondents tend to assume they are a practicing member of that faith.

More generally, questions intended to measure tolerance (aka “social distance” measures) may prime respondents to think about relatively intense versions of the identity specified. For example, if a survey question asks about a Muslim, the respondent is likely to imagine a practicing Muslim and answer accordingly. The same is broadly true for other religious groups.

In some ways, this may be a good thing for survey research. It means that respondents tend to pick up on, and react to, the religious aspects of any religious group that a survey asks about.

But it may also complicate survey researchers’ ability to measure religious tolerance or social inclusion. Respondents may be less opposed to interreligious marriage (and, by extension, indicate greater tolerance or inclusion) if we ask about specific traits or behaviors, rather than asking about a broad group of people who vary in their levels of religious practice.

Indeed, our research has shown that Muslims around the world hold a wide range of religious, political and social views, that many Christians in Western Europe are nonpracticing, and that increasing numbers of Jews in the United States identify as Jewish culturally, ethnically or by family background rather than by religion.

Areas for future research

We conducted this experiment in Australia, a country where, for many years, most of the population has identified as Christian. But recent decades have seen rapid increases in the share of Australian adults who do not identify with a religion, as well as increasing shares who identify with religions other than Christianity, such as Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and Sikhism. Religion does not appear to be a particularly strong factor in Australians’ national identity. Only 18% of Australians say it is somewhat or very important to be Christian to be truly Australian, according to a 2023 Center survey.

Although this experiment may offer valuable lessons on how to design and interpret survey questions about religious tolerance, more research is needed to determine whether these results would replicate in a similar way in other countries.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.